When I was finishing up The Myth of the Rational Voter, I needed citations on a fact that “everybody knows” – that bad weather depresses voter turnout. I was surprised by how little evidence I found. But last night, my student Jared Barton alerted me to the existence of a high-quality article on this very topic, published just a few months after my book appeared. From “The Republicans Should Pray for Rain” (Journal of Politics 2007):

We examine the effect of weather on voter turnout in 14 U.S. presidential elections. Using GIS interpolations, we employ meteorological data drawn from over 22,000 U.S. weather stations to provide election day estimates of rain and snow for each U.S. county. We find that, when compared to normal conditions, rain significantly reduces voter participation by a rate of just less than 1% per inch, while an inch of snowfall decreases turnout by almost .5%. Poor weather is also shown to benefit the Republican party’s vote share. Indeed, the weather may have contributed to two Electoral College outcomes, the 1960 and 2000 presidential elections.

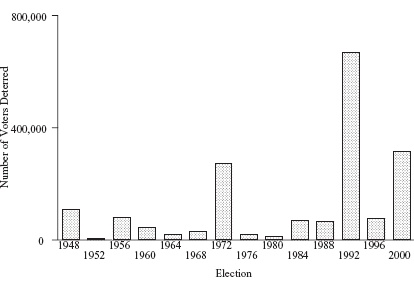

Nice graph of “Estimated Number of Voters Deterred by Precipitation on Election Days”:

More [footnotes omitted]:

[W]e simulated the partisan vote share in each state (aggregating county vote totals so as to mimic the Electoral College) under two hypothetical scenarios, which we then compare to the actual electoral results. In the first scenario, we assume no rain or snow. In the second, each county has the maximum rainfall experienced by that county during all the election days in our analysis. We do the same with the snow variable.

[…]

Under the maximum rain and snow scenario, Republican presidential candidates would have added Electoral College votes in 1948 (53 votes), 1952(10 votes), 1956 (13 votes), 1964 (14 votes), 1968 (35 votes), 1976 (43 votes), 1984 (10 votes), 1992 (13 votes), 1996 (8 votes), and 2000 (11 votes). None of these additional Electoral College votes would have led to a different occupant of the White House. In 1960, however, our results indicate that Richard Nixon would have received an additional 106 Electoral College votes, 55 votes more than needed to become president…

The results of the zero precipitation scenarios reveal only two instances in which a perfectly dry election day would have changed an Electoral College outcome. Dry elections would have led Bill Clinton to win North Carolina in 1992 and Al Gore to win Florida in 2000. This latter change in the allocation of Florida’s electors would have swung the incredibly close 2000 election in Gore’s favor.

READER COMMENTS

David R. Henderson

Feb 11 2011 at 11:20am

Bryan,

I agree with your bottom line. But the authors made a mistake. And correcting their mistake makes their point even stronger. If their number of 43 votes for the 1976 Prez election is correct, then Gerald Ford would have defeated Jimmy Carter.

Comments are closed.