I finally finished Crime and Punishment, and was rewarded with two more great Leninist diatribes that predate the dictator‘s birth. The first is a confrontation between murderous intellectual Raskolnikov and his sister:

“Aren’t you half expiating your crime by facing the suffering?” she cried, holding him close and kissing him.

“Crime? What crime?” he cried in sudden fury. “That I killed a vile noxious insect, an old pawnbroker woman, of use to no one!…Killing her was atonement for forty sins. She was sucking the life out of poor people. Was that a crime? I am not thinking of it and I am not thinking of expiating it, and why are you all rubbing it in on all sides? ‘A crime! a crime!’ Only now I see clearly the imbecility of my cowardice, now that I have decided to face this superfluous disgrace…”

“Brother, brother, what are you saying? Why, you have shed blood?” cried Dounia in despair.

“Which all men shed,” he put in almost frantically, “which flows and has always flowed in streams, which is spilt like champagne, and for which men are crowned in the Capitol and are called afterwards benefactors of mankind. Look into it more carefully and understand it! I too wanted to do good to men and would have done hundreds, thousands of good deeds to make up for that one piece of stupidity, not stupidity even, simply clumsiness, for the idea was by no means so stupid as it seems now that it has failed…(Everything seems stupid when it fails.) By that stupidity I only wanted to put myself into an independent position, to take the first step, to obtain means, and then everything would have been smoothed over by benefits immeasurable in comparison…

The second is Raskolnikov’s final inner monologue after he confesses. Even in Siberian prison, the same banality:

“In what way,” he asked himself, “was my theory stupider than others that have swarmed and clashed from the beginning of the world? One has only to look at the thing quite independently, broadly, and uninfluenced by commonplace ideas, and my idea will by no means seem so…strange. Oh, skeptics and halfpenny philosophers, why do you halt half-way!”

“Why does my action strike them as so horrible?” he said to himself. “Is it because it was a crime? What is meant by crime? My conscience is at rest. Of course, it was a legal crime, of course, the letter of the law was broken and blood was shed. Well, punish me for the letter of the law…and that’s enough. Of course, in that case many of the benefactors of mankind who snatched power for themselves instead of inheriting it ought to have been punished at their first steps. But those men succeeded and so they were right, and I didn’t, and so I had no right to have taken that step.”

How was Raskolnikov’s theory “stupider than others that have swarmed and clashed from the beginning of the world?” To repeat myself:

The key difference between a normal utilitarian and a Leninist: When a normal utilitarian concludes that mass murder would maximize social utility, he checks his work! He goes over his calculations with a fine-tooth comb, hoping to discover a way to implement beneficial policy changes without horrific atrocities. The Leninist, in contrast, reasons backwards from the atrocities that emotionally inspire him to the utilitarian argument that morally justifies his atrocities.

Notice the utter vagueness of the “hundreds, thousands of good deeds” Raskolnikov uses to justify murder. Then compare it to Raskolnikov’s fawning ode to the bloodshed of “great men”:

“Which all men shed,” he put in almost frantically, “which flows and has always flowed in streams, which is spilt like champagne, and for which men are crowned in the Capitol and are called afterwards benefactors of mankind.”

The irony is that Raskolnikov is one step away from a great truth: Most of history’s “great men” were criminals who murdered anyone who denied that they were “benefactors of mankind.” If only Russia had an Acton to reply:

I cannot accept your canon that we are to judge Pope and King unlike other men, with a favorable presumption that they did no wrong. If there is any presumption it is against the holders of power, increasing as the power increases. Historic responsibility has to make up for want of legal responsibility. Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men…

READER COMMENTS

liberty

Mar 29 2012 at 8:25am

What about the Leninism of rigid libertarians? For example, what about when a libertarian policy, such as privatization, may cause many individuals to lose their jobs and livelihoods, homes, and communities are torn apart, but the libertarian is against any support from the government, even transitional assistance?

Aren’t these ‘casualties’ of libertarian policy? Do libertarians go over their “calculations with a fine-tooth comb, hoping to discover a way to implement beneficial policy changes without horrific atrocities”? Or do they often ignore, downplay, or excuse the consequences of their policies?

My brother told me once, back when I was a more rigid libertarian, that I sounded like a Leninist – because I said that some might be hurt by allowing the market to correct, but it was necessary in order to get back on a stable path – at the time I thought he had it backwards, but now I think I see what he meant.

slim934

Mar 29 2012 at 10:21am

“My brother told me once, back when I was a more rigid libertarian, that I sounded like a Leninist – because I said that some might be hurt by allowing the market to correct, but it was necessary in order to get back on a stable path – at the time I thought he had it backwards, but now I think I see what he meant.”

He does have it backwards. It is the state monopolists now who are harming the rest of society through the use of the legal system to extract economic rents for themselves. There is no arguing backwards from some crime committed to rationalize the act. The act of stopping the disguised theft (which is what those state instituted service monopolies are) is the act of stopping an ongoing crime.

That of course is to say nothing about how muddled this entire concept becomes in relation to voluntary exchange. Afterall, how many carriage makers went out of business and otherwise proceeded to lose their livelihood with the advancement of the car? Should everyone be compensated when people choose not to trade with them?

liberty

Mar 29 2012 at 11:08am

“That of course is to say nothing about how muddled this entire concept becomes in relation to voluntary exchange. Afterall, how many carriage makers went out of business and otherwise proceeded to lose their livelihood with the advancement of the car? Should everyone be compensated when people choose not to trade with them?”

No, but two things do apply. First of all, when this occurs “naturally” in markets, it is somewhat foreseeable. After all, when firms are able to see that people might want automobiles, invent them, and begin to market them, those working in the buggy business have a chance to retrain and get work in the automobile business – or at least to make preparations for when they will be put out of business. Second, this is arguably a role for government: they can help with transition assistance, whether in the form of unemployment insurance, dole or basic income, retraining, or something else. Yes, the market may provide this and if so this may be as good or better than government provision, but this is debatable.

In contrast, when government privatizes, it often does it in a sudden and swift way. Those employed in the public firms have no chance to foresee the market shift and take care of their own situation, and government – having previously promised them jobs – now does have true accountability. It is their duty to release them in as harmless a way as possible. (Not to mention their duty to truly privatize rather than handing their friends businesses in exchange for payoffs.)

Consider Margaret Thatcher’s “privatization” in the UK, and the suffering of workers who suddenly lost jobs, homes, and communities. It may have been wrong to subsidize that industry for so long – but it was also wrong to pull the rug out from under them in one fell swoop, leaving communities devastated for decades.

Of course, in some cases the workers did have advance notice – and instead of a strike, they could have looked elsewhere for work. This is easier said than done though, if your whole town will lose its major source of income. Some towns became ghost towns for decades. The least Thatcher could have done for these workers is offer a bit of sympathy and transition assistance considering it was government that initially made those towns dependent upon the industry in the first place, by monopolizing the industry.

liberty

Mar 29 2012 at 11:50am

Public opinion slowly went against the strikers, in the case of coal mining, according to Wikipedia and it’s sources (see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/UK_miners'_strike_(1984%E2%80%931985)#cite_note-King-29)

Yet there was still a lot of hostility against Thatcher for not offering assistance. See, for example, Spitting Image:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SUkMqQ6lKm8

And many communities, as I said above, were devastated for decades.

Nathan Smith

Mar 29 2012 at 12:05pm

Bravo for the reference to Acton, and for hard thinking about Dostoyevsky. However, is it really possible for a utilitarian to “check his work?” First of all, economists know very well that utility in our sense of the term (strictly applied) is not interpersonally comparable. So there is no way of weighing one life lost against many good deeds. Second, even if it were, the consequences of a murder are extremely hard to predict.

My reading of Crime and Punishment is that it’s (among other things) an indictment of utilitarianism in general, and a poignant testament to human rights. We simply do not have the authority to kill our fellow man. And the fact that Raskolnikov’s reasoning is so slovenly, and ends up looking absurd even in terms of Raskolnikov’s own self-justifying ethos, is part of the point. Most theoretical utilitarians (doubtless including Bryan, if he actually is a utilitarian) have never seriously contemplated themselves personally committing a murder for the common good, even if their ideas would in theory endorse it. Once one begins seriously to contemplate such a thing, it warps the mind, and one ends up like Raskolnikov. I think Dostoyevsky represents this brilliantly, showing how Raskolnikov is ruined by his nerves and cannot even carry out his original purpose, which in an alternative universe where human rights were not a sacred and binding obligation laid upon all mankind, would have been quite plausible, namely, to advance the career of a young, generous-minded and clever but very poor, student, by removing a wicked old parasitic moneylender. (Suspending one’s disbelief and accepting for the moment Dostoyevsky’s apparent, though no doubt mistaken, view that pawnbrokers are parasitic.)

liberty

Mar 29 2012 at 12:12pm

Sorry, one last post.

From the excellent, I think all would agree, Commanding Heights series, which includes many Hayekian thinkers as well as many from opposing POV, here is a quote from Gordon Brown – first explaining the cost to the strikers (which, some might say, would make someone a Leninist if they don’t care):

“GORDON BROWN: The coal mining strike of the early 1980s was a tragedy for so many of the mining families that were involved in it. They were denied proper benefits for a year. Many were arrested. Many families never recovered from this

dispute, and it was a human tragedy.

Then he explains:

“It was always the case that the coal industry of the country had to reform and modernize. It was always the case that there were going to be less jobs in the coal industry in future years. But like it or not, the Thatcher government at the time gave people the impression that they didn’t care whether there was a mining industry at all. They didn’t care … because people felt that the government neither cared about the future of

communities, nor did they care about there being a balanced policy towards energy”

It was the feeling that they didn’t care that I am trying to get at. If they (the government, no matter who ran it at the time) hired the workers in the first place, they should care what happens when they fire them. They are responsible.

This is the complexity that I think a lot of libertarian thought misses.

David W

Mar 29 2012 at 1:03pm

Liberty, I beg to differ. I’ll grant that in the situation you describe, it’s likely to be better tactics to pay for transitional support (so long as that is actually what you get). For that matter, with the modern complexity of government, it’s quite possible for someone to benefit from immoral actions of others, without knowing it.

Nevertheless, if I take your argument to the logical conclusion, it argues, for instance, that Lincoln’s government ought to have compensated the slaveowners. That increasing police presence ought to come with payments to the muggers in the area. That stolen property ought not be seized and returned, but purchased.

Your argument assumes, implicitly, that the choice of government action or private action is merely a question of efficiency, maximizing utility, and carries no moral weight. And that the status quo is the property of those who benefit from it, and should not be taken without due process and compensation.

I disagree with these assumptions, entirely. I’ll acknowledge that enough people believe it, that it’s correct tactics to compromise with them. Maybe even more, that some change cannot be accomplished at all unless those affected are compensated, or costs of similar magnitude are inflicted through force (maybe Lincoln should have bought the slaves, to save the lives of the war). But I won’t acknowledge that there’s any moral weight to their arguments.

Evan

Mar 29 2012 at 1:31pm

Leninists remind me of the Underpants Gnomes from South Park.

Step 1. Slaughter a ton of people.

Step 2. ?

Step 3. Utopia!

@Nathan Smith

You may be interested in Eliezer Yudkowsky’s utilitarian defense of deontological ethics. He basically argues that evolution has programed humans to crave power, but to also convince ourselves that we are seeking power for a greater good so that we may still appear like good, ethical persons to our potential allies. For that reason humans cannot be trusted to make utilitarian calculations in most situations. So he argues that deontological rules like human rights are more effective in practice, even if utilitarianism is correct in principle.

He does bite the bullet and say that a nonhuman creature that didn’t have a “be corrupted by power” subroutine in its programming would be totally justified in personally killing people for the greater good.

Michael

Mar 29 2012 at 10:28pm

Liberty, you are confusing tolerating the natural state of order with purposely causing harm.

Progress destroyed those carriage-maker jobs. Allowing that progress to occur is very different from bludgeoning someone and emptying their pockets for orphans.

Gian

Mar 30 2012 at 3:02am

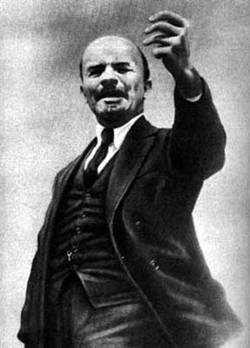

“committing a murder for the common good” is an oxymoron that only a utilitarian can think of.

Lenin is merely a consistent utilitarian. Caplan’s description of a utilitarian is no compliment.

liberty

Mar 30 2012 at 5:36am

“Your argument assumes, implicitly, that the choice of government action or private action is merely a question of efficiency, maximizing utility, and carries no moral weight. ” – David W.

Perhaps I am, but then comparing people who work at jobs at state-run factories with muggers and thieves is just silly. Maybe the government can be said to be stealing, but accepting a job (or even accepting a welfare check) if it is being offered is not an immoral act. Even many libertarians, even Ron Paul, wind up using the argument at some point or another that they’ve already paid taxes into the system and so long as it exists they would be too much worse off not to accept what is available to them.

Hence, even if what the government is doing is immoral (and I am not a natural rights libertarian who believes every act of government is theft, so I am only accepting this for the sake of argument) it is government that is immoral, not the individuals working at state-run or state-subsidized firms. This is in contrast to slave-owners who knew that keeping slaves, whatever government said about it, was immoral; same with muggers, thieves, etc.

Michael: Yes, I made this distinction when I said that government is in a different position when it is merely creative destruction in action. However, when the state created an industry or monopoly to begin with, it is not merely creative destruction when it closes it down. True, the market is now able to work – but the form the destruction takes is very different when it had previously been state run.

Think of the Soviet collapse, or any transition from communism — mass unemployment across the whole country, huge inflation, extreme shortages, dipping and spiking prices, and so on. All necessary for the market to find its footing, true. But since the government created the mess, if there is any way for the government to help with the transition(without making things worse!) then it would be the least it could do, to make up for what it had put the people through and for relieve their temporarily worse situation. (Since it is probably impossible to know how best to manage the transition better than simply freeing things fast – which might be painful but hopefully short – then the best thing government can do to ease the transition is offer some kind of basic income/insurance taken from taxation of those previously wealthy through the old system, etc.)

Tracy W

Mar 30 2012 at 6:18am

Liberty: Those employed in the public firms have no chance to foresee the market shift and take care of their own situation, and government – having previously promised them jobs – now does have true accountability. It is their duty to release them in as harmless a way as possible.

You make the mistake of assuming that the government is somehow distinct from people. If public sector employees don’t bear any responsibility for their market shift, then who does? Why should MPs, or unrelated taxpayers, or future taxpayers, be expected to know more about such things than the people actually working in those industries? Bear in mind that there’s too much in the mordern economy for any one person to know everything.

As for governments, having previously promised them jobs, why did those governments promise them jobs? I suspect to get the votes, and perhaps the donations, of said employees. As voters, the employees bear the responsibility for that government policy. (Obviously not so applicable to citizens of non-democracies but you cited the case of Margaret Thatcher’s UK.)

Your line of argument only makes sense if there’s some reason to think that government is wiser than public sector employees. But as government is inevitably made up of people, this seems extremely unlikely.

Tracy W

Mar 30 2012 at 8:56am

Liberty: then the best thing government can do to ease the transition is offer some kind of basic income/insurance taken from taxation of those previously wealthy through the old system

“Previously wealthy through the old system” – which means those who gained from state subsidies of their industries. This does sound rather circular.

liberty

Mar 30 2012 at 9:15am

Tracy W:

Government employees don’t have to be smarter or know more about anything except the fact that they are going to axe the jobs. That’s all they need to know in order to offer some transitional assistance.

You ask: “If public sector employees don’t bear any responsibility for their market shift, then who does?” Nobody bears responsibility for a shift in the market, but that does not mean that assistance cannot be given; and the government does bear responsibility for giving them the public sector jobs to begin with.

Again, nobody needs to be wise to offer transitional assistance – just kind, and not Leninist about steamrolling over people in order to bring about a desired end.

liberty

Mar 30 2012 at 9:19am

The “Previously wealthy through the old system” comment was with regard to the specific case of the post-communist transition: because some did very well under that system by exploiting others using the state’s power, and this could be used to fund transitional assistance, with the added benefit of making the distribution at the state of the new system more fair.

One could I suppose do the same within an industry as its privatized, but it makes a lot less sense because some usually don’t exploit others very much within one industry or at one company. However, if some executives did make a lot of profit in the nationalized industry I suppose this money could be used. But I was not referring to this in my post – I was speaking only of post-communist transition.

Tracy W

Mar 30 2012 at 9:39am

Liberty:

You have missed the point of your own argument. Before you were arguing that the government had a duty to provide transition assistance. To quote yourself:

“It is their duty to release them in as harmless a way as possible. … The least Thatcher could have done for these workers is offer a bit of sympathy and transition assistance…”

Now you are saying that the government could offer assistance. But just because the government can do something doesn’t mean that the government should do that. The government could take 5 cents from everyone in the country and give all that money to me, but that’s hardly a case for the government doing so.

As I understood it, you were making the argument that the government should (not just can, but should) give transition assistance, on the basis that the government had promised the workers jobs in the first place, and that the employees of public firms had no chance to foresee the market shift. That’s the argument I was criticising. If I have misunderstood what you were arguing, please let me know.

the government does bear responsibility for giving them the public sector jobs to begin with.

Yes, but the group that the government bears responsibility to is all taxpayers, not just those lucky enough to get government jobs. Given that some people have benefited from government jobs in the past, why should all taxpayers, who know far less about the ins and outs of that job than the people doing them, pay transition response to those public sector employees? Taxpayers have already paid once, for the subsidies, and you now want to charge them again, for transition assistance to the beneficiaries of the subsidies? What’s the moral basis for that?

Tracy W

Mar 30 2012 at 9:49am

Liberty: One could I suppose do the same within an industry as its privatized, but it makes a lot less sense because some usually don’t exploit others very much within one industry or at one company. . However, if some executives did make a lot of profit in the nationalized industry I suppose this money could be used.

You appear to be confused about how subsidises work. What happens is that they take money from the general population and transfer it to people within an industry. The “exploitation”, if you wish to call it that, benefits those in the industry at the expense of the general population.

You also appear to be bit a confused about the meaning of the word “nationalised”, it’s the process of taking an industry or assets into government ownership. The government, as owner, therefore gets the profits (if any) from that industry, not the executives. Executives get paid, they may get bonuses, profits are what’s left after that, and all the other costs of the industry. (Of course, if the managers of the nationalised industry steal from it, they should be punished like any other government employee who steals government assets).

Your original argument, I will remind you, was that “then the best thing government can do to ease the transition is offer some kind of basic income/insurance taken from taxation of those previously wealthy through the old system”

You didn’t restrict your assertion here to those who made profits, or to people who exploited others within the industry. And if you do plan to restrict taxation in such ways, then there become fewer and fewer people to pay the taxes to fund your transition.

In the case of the post-Communist transition, the problem with Communism is that the only wealthy people were the ones high up in the Communist parties, who were managing the transition (or had been killed by angry mobs, or fled the country). It’s hard to get people to agree to tax themselves, and it’s hard to tax people who aren’t there. If Communism had generated lots of wealth, there wouldn’t have been the need for the transition away from it.

liberty

Mar 30 2012 at 10:23am

Tracy W – I am not confused. You are fisking my argument, and accusing me of changing my position, which I am not.

Again, the suggestion to tax those who benefited from *the old system* was only with regard to post-Communist transition, in which a system was actually changed.

With regard to privatization, I merely said that because the government had promised people jobs and then took them away, I think there is a case that – in order not to be Leninist about breaking eggs – the government should offer transitional assistance to these people so that they can get new jobs, without their children starving in the interim.

Yes, I understand that the taxpayer will be getting screwed again during this transition – but that does not absolve the government of its duty to treat the people it has previously made a promise to well during the transition away from the promised program. Again, *if* we care about not being “Leninist” in our policies, which was the argument in the thread.

liberty

Mar 30 2012 at 11:15am

I’m going to summarize my position one more time, to be completely clear:

(1) The individuals working at a nationalized firm were not immoral for taking the jobs any more than any libertarian who never voted for a post office or highway system is immoral for posting a letter or driving on the road. Libertarians want more in the private sphere than the public because they understand that not everyone votes for things that win with 51% of the vote – so why assume that all the workers at a nationalized firm are immoral for working there? What if the state nationalized the industry, leaving them with no more chance to get away from working there than any libertarian does of avoiding the highways or the post office? The workers are not to blame for working there.

(2) When the state pulls the rug up out from under them in an instant, they are not left in the same position as they would have been had the state never nationalized the industry. Just as post-communism the people are not left with the market they would have had without it, or even the one they had before communism, nor are the workers left with the market conditions that would have been if the state had not intervened — they are left in a much worse position.

(3) So given the fact that it isn’t the workers fault that the state took over their industry, and they are left much worse off after the state leaves than they would have been had the state never intervened, the state would be cruel (and Leninist) for not offering transitional assistance. Yes, it will cost the taxpayers a little bit more – but the few workers that must bear the brunt of the state’s actions can be hurt a lot less by hurting the mass of taxpayers a little bit more. It’s the state – or democracy – that created the conditions. The state can also avoid hurting these few people most affected while it fixes its mistake.

It is wrong to assume the workers are bad and immoral, and wrong to assume they did better in the state job than they would have in the market – its wrong to assume they wanted the state job (though some might have) and wrong to treat them all as a homogeneous lump.

So, to not be “Leninist”, we should remember that some workers might have been hurt first by the state nationalizing the industry and then again by the state privatizing it, and to not offer assistance during the latter is to not worry about breaking eggs.

Tracy W

Mar 30 2012 at 12:38pm

Liberty:

You do indeed appear to be changing your position. Earlier you said:

” It is their duty to release them in as harmless a way as possible. … Consider Margaret Thatcher’s “privatization” in the UK, and the suffering of workers who suddenly lost jobs, homes, and communities. It may have been wrong to subsidize that industry for so long – but it was also wrong to pull the rug out from under them in one fell swoop, leaving communities devastated for decades.”

And now you are saying “I think there is a case that …the government should offer transitional assistance to these people so that they can get new jobs, without their children starving in the interim.”

Now in Margaret Thatcher’s UK, people were paid the dole, so children didn’t starve in the interim. And you earlier criticised Margaret Thatcher’s UK for a lack of assistance. So it struck me that earlier you were arguing for assistance that went beyond merely preventing people’s children from starving to death, in particular “as harmless as possible”.

As for the workers in a nationalised industry, in a country like the UK it strikes me as safe to assume that they did indeed benefit from that job, if not they’d’ve left to take another one. So how are these people left in a much worse position? Didn’t they get all the benefits for years of those jobs? For all the criticisms of pre-Thatcherite England, I’ve never heard that it was in the habit of enslaving its population. The owners of capital might have been harmed by nationalising the industry, but not the people who chose to keep working in it (except perhaps in the broader sense that all Brits were worse off because of such policies).

It also remains the case that to the extent that the workers voted for governments that subsidised their industries they are responsible for those policies.

If you are talking about Communist countries, then I agree entirely that workers did not have an option, and were almost certainly worse off. The problem with Communism however is that it did not generate wealth, so there wasn’t the wealth to pay for the transition (and Communism covered so much of the workforce that taxpayers and workers were the same anyway).

Comments are closed.