The Museum of Jewish Heritage in NYC features an outstanding exhibit on European Jewry’s struggle to escape from Hitler’s clutches. Throughout the 1930s, the Nazis officially encouraged Jewish emigration. The catch: By definition, every emigrant from Nazi territory had to become an immigrant to non-Nazi territory – and by the 1930s, almost every country tightly restricted immigration of all kinds.

“Almost every country” includes, of course, the United States. When Jews in the Russian Empire faced pogroms before World War I, about two million found refuge in America. By the 1930s, such a welcome was unthinkable. Why? Public opinion.

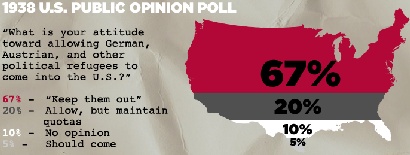

Results from a 1938 survey: When asked “What is your attitude toward allowing German, Austrian, and other political refugees to come into the U.S.?,” a bare 5% of Americans favored raising the immigration quota. Two-thirds didn’t even want to fill the extremely low quota of the era.

Slightly different wording yields very similar results: “If you were a member of Congress, how would you vote on a bill that would open the doors of the U.S. to a larger number of European refugees than are currently allowed?”

American immigration policy in the 1930s – the policy that trapped millions of Jews in Nazi territory – wasn’t a weird aberration of a by-gone era. It epitomized the misanthropic mind-set that continues to drive immigration policy around the globe.

READER COMMENTS

Bernard King

Aug 4 2013 at 12:50am

This made me think about modern day Kurds and other ethnic groups that don’t have a nation state where they can live without persecution. Possibly Iraq now, but that remains to be seen. But even in Iraq they must as minorities still live under the threat of persecution.

FredR

Aug 4 2013 at 4:08am

“When Jews in the Russian Empire faced pogroms before World War I, about two million found refuge in America. By the 1930s, such a welcome was unthinkable. Why? Public opinion.”

Why did public opinion change?

Salem

Aug 4 2013 at 6:46am

This is extremely unfair. A large part of the reason some countries were and are reluctant to take in more refugees is others not doing their fair share. In the early part of the twentieth century, the USA – to it’s great credit – took in large numbers of refugees, including Jews, while other wealthy countries, particulary in western europe, acted as free-riders, allowing their consciences to be salved while not incurring and of the expense or problems. We see the same situation today, where France pushes its asylum seekers onto Britain. This is a public goods issue, which unfortunately treaties have only partially resolved.

Moreover, your explanation, a general misanthropy by numbers, is clearly woefully inadequate. It cannot explain the change in American policy, given that you think that the anti-foreign bias is a deep aspect of our politics and psychology. Did human nature change between 1910 and 1930?

@Bernard King: In Iraq right now, the Kurds are not being persecuted, but rather doing the persecuting. See e.g. Kirkuk. It is folly to think that you can assure proper treatment by giving each ethnic/linguistic bloc a state, as these states are no more likely to respect their own minorities than were the larger ones. There is no substitute for liberal values.

Tom West

Aug 4 2013 at 9:29am

I admire Bryan’s pro-immigration stance even if I cannot entirely share it (for entirely selfish reasons – I’m happy accepting current levels of Canadian immigration, but I think that open borders would result in cultural change at a rate considerably faster than I’m comfortable with).

However, I have to say that this issue and an issue over mandatory parking provisions at the Marginal Revolution blog make it pretty clear that many who style themselves Libertarian embrace Libertarianism only so far as they imagine that extra freedoms benefit them directly. In other words, the goal is a specific outcome, and the principles are only a tool to achieve that outcome (and likely to be discarded when the principles dictate an undesirable outcome.)

In this way, it mirrors most of the left (including myself) who desire to alleviate the suffering of our fellow human beings not because we’re principled, but because we don’t want to be directly exposed to human misery.

Pretending one has a set of lofty principles is very comforting for most of us, but my (cynical) prediction is that if people like Bryan are successful in pushing aside all the half-baked justifications why one can be a Libertarian and not support open borders, most will choose to give up their principles rather than their comfort.

Perhaps it’s why I don’t see the truly principled on the left push for open borders. Why alienate people who believe themselves to be truly caring and at least contribute to that principle to some degree?

S

Aug 4 2013 at 11:42am

Sounds more like chauvinism by numbers to me. Though being accused of misanthropy, for some strange reason, is more socially palatable than racism. So I guess you cant be accused of being completely uncharitable. 🙂

Seriously though, why the choice of misanthropy? Hatred of all people is not required for a strong sense of ingroup loyalty. They are even mutually exclusive along some margin. One could even argue that individualism is fundamentally more misanthropic than chauvinism, so it seems like an odd choice to some degree.

David Curran

Aug 4 2013 at 12:42pm

In Popular Crime Bill James claims the anarchist terrorism of just after WW1 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacco_and_Vanzetti

lead to a hatred of foreigners and immigration restrictions. He blames the great depression on the labour effects of this. It would be odd if this effect of immigration could be blamed on terrorism as well.

Philo

Aug 4 2013 at 12:52pm

I hadn’t realized the polling numbers were so overwhelming; one does wonder what caused the change from the more welcoming—or at least non-rejecting—attitude of the previous generation.

As an aside, you might have mentioned that many of the German/Austrian Jews were unwilling to emigrate: they were German/Austrian patriots!

Joseph Hertzlinger

Aug 4 2013 at 4:32pm

““On or about December 1910 human nature changed.”—Virginia Woolf

For some reason, many people celebrate the change … but it had a downside or two.

MingoV

Aug 4 2013 at 6:32pm

“On or about December 1910 human nature changed.”—Virginia Woolf

A quote from Ms. Woolf proves nothing. Show me some statistics and the methods for obtaining them.

The information I’ve read over the years was that most people, over the entire history of the USA, were anti-immigration except for their own or closely related ethnic groups. The English-Americans didn’t want the Irish, Italians, Poles, etc. Whites did not want Asian immigrants. I never read about an inexplicable conversion of the populace to a pro-immigration position in 1910. I suspect biased surveys.

nicholas glenn

Aug 4 2013 at 6:58pm

I think the great depression triggered a lot of the negativity toward immigrants. The belief that they are taking all of our jobs. You see the same kind of attitude with the blue collar workers regarding Hispanics today. They honestly believe that if you deported all of the illegal immigrants full employment would magically reappear. They’re not bad people just a little confused.

Mark V Anderson

Aug 4 2013 at 8:43pm

Yes, nicholas, I’m sure it was a matter of jobs. In the Great Depression, with unemployment above 10%, no one should find surprising that folks wouldn’t want a bunch of new immigrants coming in, most of them undoubtedly laborers, wanting the same jobs as many of those without work already. Bryan’s invoking of misanthropy is totally unnecessary and unfair. It is simply people looking out for their own economic well-being. How non-libertarian! (<; And they weren't even wrong. Regardless of whether one believes that these immigrants would end up creating as many jobs as they took, does anyone deny that in the short run they would come to America looking for the same jobs as the folks already here? At least in the short run, greater immigration would increase the level of unemployment. Just as it would today.

libertarian jerry

Aug 4 2013 at 11:30pm

Mingo’s point about immigration is correct. Many Americans in the past feared immigration for 2 reasons. 1st. Immigrants were competition for jobs,especially during times of economic downturn. This was true not only for immigrants from foreign countries but also internal Black immigrants from Southern States that were coming North looking for work in industry. 2nd. Many people were against immigration on cultural or religious grounds. There was,for instance,during the first part of the 19th Century an irrational fear of the Catholic Church infiltrating and taking over America. Today,many of these same fears are present. That is a fear of alien cultures and religions,especially Islam. The fear of taking jobs is marginal and has been replaced by the fear of immigrants getting on the government welfare gravy train with their “anchor babies” being used as a method of achieving this aim.

William Peterson

Aug 5 2013 at 3:05am

One other point which may be relevant (particularly in the modern world) relates to the cost of migration (both financial and discomfort). If this is high relative to wages, as it was in the era of sailing ships, then migrants will be seen favourably as enterprising individuals making a better life for themselves. Refugees, and those who are pushed into migration by famines, are more likely to be seen as a threat to the ‘native’ population.

It may be worth noting that most countries did not control immigration in the 19th century, and that some (eg France) continued to encourage it in the 1920’s to replace war losses. As others have pointed out, it’s the Great Depression which changes attitudes.

guthrie

Aug 5 2013 at 11:32am

@Mark V Anderson,

How libertarian is it to deny an American employer the freedom to employ whomever they see as the best fit for the job their offering, regardless of that potential employee’s origin?

How does it express love of humanity to deny another human the choice to move to a place of relative freedom and opportunity, from a place where they are almost sure to be killed before their time?

Ral;h

Aug 5 2013 at 11:37am

Why would we want to accept sharia arabs whose culture is so different than ours and they demand that they be accepted? I suggest that we have no room for them if we want to keep our freedoms intact.

ralph

Aug 5 2013 at 11:41am

You have rejected my previous comment for an invalid reason as I have not sent so many comments before. Is this the way you refuse a comment that you don’t like?

NZ

Aug 5 2013 at 11:57am

Isn’t a major component of this–and one most people don’t like to think about–the inequality of immigrant stock?

It’s easy for me to imagine that the US would benefit on net from an inpouring of Jews, especially ones from Europe or the Soviet bloc. (You know, the ones who eventually produce Milton Friedmans and Bryan Caplans.) It’s harder to imagine a similar benefit from an inpouring of uneducated, mostly unskilled Mexicans. (A basic yardstick: who would you prefer move in next door to you?)

Soviet rulership seemed to recognize this. After WWII, they did the opposite of the Nazis and imposed strict bans on Jewish emigration, even though Soviet Jews wanted to leave. The Soviets didn’t want to part with so many of their doctors, scholars, scientists, and chess masters.

Compare that with, say, the Mexican government’s attitude towards illegal immigration into the US, which is basically “Good riddance.”

Ak Mike

Aug 5 2013 at 1:04pm

Let me correct those who believe that the Great Depression caused the anti-immigration sentiment in the United States. In fact, the door was slammed shut on open immigration in this country with the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, passed during the era of Coolidge prosperity. No major immigration restriction was imposed during the Depression, although existing law was vigorously enforced.

Growing racism rather than strictly economic concerns was probably the motivation. The law allowed for continued immigration from northern Europe but limited inflows from southern and eastern Europe. Certainly one factor hard to disentangle from racism was the reaction to the wave of violent anarchism that had assassinated leaders all over Europe, and caused atrocities in the United States such as the Wall Street bombing and the robbery/murder attributed to Sacco and Vanzetti.

libertarian jerry

Aug 5 2013 at 5:38pm

Google the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952 for more recent legislation on immigration. The measure passed by overriding Truman’s veto. And,although modified over time,it is still the law of the land

eccentric-opinion

Aug 5 2013 at 8:17pm

NZ:

“A basic yardstick: who would you prefer move in next door to you?”

By that yardstick, uneducated rural whites and inner-city blacks would be deported from America. But no one is suggesting deporting citizens.

djf

Aug 6 2013 at 8:21pm

Why did America reduce the number of immigrants it took after WW I? Gee, I’m not an economist, bu could it be that the change had something to do with the fact that there was no longer a labor shortage in the country, and continuing to admit immigrants at the pre-WW I rate would have been contrary to the interests of the large majority of citizens? Here’s another wild guess – maybe it was thought that reducing downward pressure on wages would reduce the often violent labor unrest the country experienced early in the 20th century. And perhaps it was thought that reducing immigration would promote assimilation of the immigrants already here. Crazy thoughts, I know.

Incidentally, pre-WW I Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe was primarily motivated by economic factors (Jews were losing their traditional economic roles in Central and E Europe) and the Jewish immigrants were not all from the Russian Empire – many were from the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Jacob A. Geller

Aug 9 2013 at 4:55pm

“Was anti-Semitism the problem? I doubt it.”

Actually in FDR’s State Department it was a huge part of the problem. I’d find the reference for this now, but you can Google it yourself. The U.S. Ambassador to Germany, William Dodd (I think), made a big deal about Hitler’s Germany and FDR basically sacked him because he was getting to be a political liability, and nobody in the State Department supported him because nobody in the State Department cared (about Jews in Germany, Jews in the U.S., nor anything else that looked “off” about Nazi Germany). He spent most of his time before the war broke out (and before his death in 1940) touring the country giving public lectures about this. Pretty harrowing stuff.

Here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Dodd_(ambassador)#Antisemitism …you’d like the guy (Bryan).

Comments are closed.