Evan Soltas has an excellent new post explaining why the Fed is likely to raise interest rates in late 2015. He thinks this policy is appropriate, but I’d like to focus on a different issue—whether this rate increase caused the Great Recession of 2008-09.

At first glance my hypothesis seems absurd for many reasons, primarily because effect is not suppose to precede cause. So let me change the wording slightly, and suggest that expectations of this 2015 rate increase caused the Great Recession. Still seems like a long shot, but it’s actually far more plausible than you imagine (and indeed is consistent with mainstream macro theory.) I’ll build up my argument in several steps:

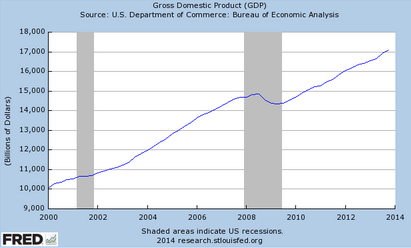

1. When I first got into blogging I suggested the Fed was to blame for the biggest fall in NGDP since the 1930s. Some countered this argument with the claim that the Fed was powerless when interest rates were stuck at zero. Later we found out that that was not true. At the time I argued that my interpretation would be proven correct when the Fed finally exited the zero rate trap. I said that at that point everyone would agree that the Fed had the nominal economy where it wanted it. Even Keynesians would have to agree that if the Fed was raising rates we did not suffer from low NGDP because of a liquidity trap, but rather because that’s where the Fed wanted the economy to be. Let’s look at NGDP since 2000:

NGDP had been rising at just over 5% for several decades, when it suddenly declined 4% between mid-2008 and mid-2009, which is 9% below trend. That was the cause of the Great Recession, not the financial crisis.

[People reject this argument for two reasons. First, they correctly note that a financial crisis is a supply shock. And second, they argue the financial crisis caused the fall in NGDP, and there is nothing the Fed could do about it. Over time these arguments have lost force, especially with the eurozone’s double dip recession caused by plunging NGDP growth. And unemployment remaining high when the banking crisis was over. But for anyone who had studied macro policy in 1933 these arguments never had much force. A banking crisis doesn’t prevent the Fed from sharply boosting either nominal or real GDP.]

In 2009 the economy was deep in recession. The Fed could have and should have tried to return to the original trend line (or at least part way back.) Of course if they had that sort of policy regime in mind, then we probably would not have had a severe recession in the first place. Asset prices crashed in late 2008 precisely because they did not expected NGDP to return to the original trend line. If they had expected a bounce back, then the fall in NGDP growth would have been much milder—more like Australia.

2. Now let’s suppose we accept modern new Keynesian economics, or market monetarism. The current path of aggregate demand (NGDP) is strongly influenced by the expected future path of AD. And let’s assume that the market correctly anticipated that the Fed would eventually exit the zero bound under circumstances similar to those described by Evan Soltas. It seems likely that NGDP growth between now and late 2015 won’t diverge much from the 4% to 4.5% growth experienced ever since mid-2009. Under that scenario, what would the “equilibrium” path of the economy have been back in 2009? Unless I’m mistaken, it’s hard to conceive of any macro model where the expected path from the trough in mid-2009 to the level of NGDP in late 2015 is anything very far from a straight line. In other words, “connect the dots.” The low of 2009 is one dot. The expected position of NGDP when they exit in 2015 is another dot. I’ll wager that when we get there the actual path of NGDP will be quite close to a straight line (not exact of course.)

The Fed’s decision to tighten in 2015 is essentially equivalent to the Fed saying to the public “all things considered we think a 4% to 4.5% NGDP growth rate is about right for the period of 2009-2016, and probably beyond.” Which is fine if that’s the way they want it. But in that case there was never any chance of the US having a fast recovery, like the 11% annual NGDP growth rate we observed in the first 6 quarters of the Reagan recovery (1983-84). The Fed literally made it impossible. The slow recovery was baked in the cake once the Fed indicated there would be no “make-up” for the undershooting of NGDP in 2008-09.

This confuses people, because they correctly believe that the Fed in general, and Ben Bernanke in particular, really would have liked to see faster NGDP growth after 2009. I agree with this perception; I believe that Bernanke and many others at the Fed (not all) sincerely wished for faster nominal growth. But they weren’t willing to do the forward guidance necessary to make that happen. That would have been a guidance that suggested some “make-up” of the NGDP shortfall, not starting a new trend line on a lower level. That make-up might have led to some above target inflation (albeit less than most people assume.) But the Fed wasn’t willing to take that step. And that made the very slow recovery inevitable.

Now back up one step, by late 2008 the markets had a growing realization that the Fed wasn’t willing (or able?) to do much about the path of NGDP. This caused asset prices to crash, and turned a mild recession into a steep recession. If the Fed had announced level targeting of NGDP along even a 4% trend line in mid-2008, the recession would have been far milder. Indeed we would have already exited the zero rate boundary by now, probably by 2012.

For those unable to understand my argument, the following exchange rate analogy might be helpful. Suppose there is an exchange rate crisis, such as the UK pound crisis of 1931 or 1967 or 1992. There is a debate over whether the markets forced a devaluation, or correctly anticipated a devaluation that the government wanted in any case. How do we know who is right? Suppose that several years later when the crisis is over the government does not try to push the exchange rate back up to the original level. They put macroeconomic factors like employment ahead of exchange rates, even when the crisis is over and the speculators are no longer pressuring the currency. In that case it’s pretty clear that the government wants a devalued currency, or at least they aren’t willing to accept the deflation necessary to prevent it. The speculators who “forced” Britain to devalue, actually merely predicted what the government was going to do in any case. We can retrospectively understand these exchange rate crises much better than we do in real time, when the sturm and drang of crisis causes emotional reactions. “It’s all George Soros’s fault!!”

Perhaps the Fed didn’t want the slow growth of NGDP, but they weren’t willing to accept the inflation that level targeting of NGDP might have required. (This is of course Paul Krugman’s argument–where I differ is that I see no expectations trap, just a conservative central bank.) The 2008 asset price crash was not a “exogenous shock” that the Fed had to valiantly fight against, but rather a correct prediction of the excessively contractionary monetary policy that was on the way. We didn’t see that with all the turmoil of the 2008 crisis, but by 2015 it will be abundantly clear that this is the NGDP that the Fed wants, or more precisely is willing to accept. And if they (will) want that NGDP in 2015, then they must also accept the very low NGDP of 2009 as an inevitable consequence. Michael Woodford has a wonderful phrase–seeing macroeconomics from a “timeless perspective.”

PS. This post might seem critical of Evan Soltas’s suggestion that the Fed should raise rates in late 2015 (if things progress as expected.) However that’s not quite what I’m saying. By now the horses have left the barn. Because this post has run on too long already, I’ll deal with his argument over at TheMoneyIllusion.

PPS. Notice my claim that with a better (more expansionary) policy, interest rates would have risen by 2012. That’s why rates are not a good way of describing the stance of monetary policy. Rather you need to look at the path of NGDP. At best an unexpected move in rates can provide insight into where the central bank wishes to see NGDP move. So the title of this post should actually read something like “The Fed being “OK” with NGDP in late 2015 caused the deep slump in 2009.” But I must live in a world where everyone thinks in terms of interest rates.

READER COMMENTS

Andrew C

Mar 13 2014 at 11:17am

This seems germane:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Newcomb%27s_paradox

TravisV

Mar 13 2014 at 11:28am

One huge element that I thought this post lacked: the importance of the Fed funds rate approaching 0% in late 2008. THAT’s the moment the markets realized that the Fed wasn’t willing (or able?) to do much about the path of NGDP. And asset value decreases accelerated.

As the Fed funds rate approached 0%, the Fed became extremely cautious. It was out of its comfort zone. Recognizing the Fed’s discomfort with unconventional monetary measures, market expectations of future demand in 2010 and 2011 collapsed, right?

As Nick Rowe has said, when interest rates fall to 0%, the Fed becomes “mute.”

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2012/02/the-mute-king.html

Its favored steering mechanism locks up right when it needs it most: a surprise fall in NGDP.

There needs to be more discussion about the Fed’s discomfort after we fell into the “liquidity trap.” It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy: if everyone believes the central bank is powerless in a “liquidity trap,” then it becomes true: the Fed is effectively powerless.

TravisV

Mar 13 2014 at 11:38am

Second point (less important):

It’s very confusing whether we should think of a financial crisis as a negative supply shock or a negative demand shock.

After all, a negative supply shock is supposed to create INFLATIONARY pressure, right? But that’s certainly not what happened in the U.S. in late 2008.

Seems to me that a financial crisis is better described as a negative DEMAND shock. Asset values crash, and, as a result, Americans tend to hoard dollars rather than spend them.

What actual basis is there for claiming that a financial crisis is more of a supply shock? The experience of emerging markets (where financial crises often result in high inflation)?

Just a very confusing issue all around. However, there certainly is a big difference between financial crises in the U.S. and Japan (inflation falls) and emerging markets (inflation surges).

marcus nunes

Mar 13 2014 at 11:44am

Fed Chairmen write and follow scripts. Some scripts are better than others. Benanke´s script was an explicit inflation targeting one. That was the reason the economy tanked and is the reason the recovery is not getting the economy back to near where it was. But it is exactly where the “scriptwriter” wants it to be!

http://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2014/03/12/fed-chairmen-as-scriptwriters/

John Hall

Mar 13 2014 at 12:15pm

I distinctly recall going to a Macroeconomic Advisers conference back in like 2009 or so and they presented the Fed Funds rate implied by the market (showing hikes relatively soon) and the Fed Funds rate implied by their models (showing hikes far in the distance). They suggested an arbitrage and were completely right. Under your ideas, it wasn’t the interest rate increase in 2015 that led to the Great Recession, it was that the interest rate increase that we now expect in 2015 was originally expected to come much earlier. I find that argument convincing.

Dan W.

Mar 13 2014 at 1:04pm

Scott,

You wrote:

“This caused asset prices to crash, and turned a mild recession into a steep recession.”

One might read this sentence as suggesting the economic recession followed the decline in asset prices. But how can that be? For every seller there is a buyer and while sellers dislike lower prices buyers benefit from them. Did you intend to convey a correlation or were you combining two ideas into one?

Put another way, the only way a decline in asset prices can cause economic damage is if the assets are backed by credit that consequently cannot be paid. In this case there are real economic losers – those who lent money that cannot be paid back.

The fallacy of NGDPLT is that it can never ensure against bad lending. No matter the forward guidance of the central bank, lenders can and will lend in excess, overconfident that the loans will be made good. Ironically, the greater the confidence in “forward guidance” the worse the credit bubble will be. And when the credit bubble pops NGDP will fall below the trend and economic destruction will follow, until prices reset to reflect a more realistic discount rate.

If your position is that NGDPLT will prevent credit shocks can you explain how?

sourcreamus

Mar 13 2014 at 1:05pm

An analogy to what caused the recession. You bump your head getting into your car and you go to the doctor. Instead of giving you aspirin he tells you to tough it out. You go around with a headache for the next several days. Is your headache the fault of the bump on the head or the lack of aspirin?

Everyone wants to focus on how to prevent bumps on the head but they are inevitable over a long enough time frame. It is better to focus on getting the doctor to give aspirin in a timely manner.

A better analogy would be one where the the patient is not supposed to have to visit a doctor but the doctor’s job is to monitor the patient and adminster the aspirin as soon as it is needed whether the patient realizes it or not. Then it would be clearer that the recession is the fault of the fed and not the financial crisis.

Scott Sumner

Mar 13 2014 at 1:35pm

Andrew, It is sort of related, but more in a single play game. This is a repeat game.

Travis good points. I wouldn’t say everyone believes the central bank is powerless, I’d say they worry the central bank thinks its powerless.

Marcus, Good point.

John, Good point, and that’s exactly why it’s a mistake to talk about interest rates. The discussion would be more fruitful if we talked about the NGDP path, or unemployment rate that would trigger a rate increase.

Dan, You are right that asset price crashes don’t cause recessions, they reflect the forces that cause recessions (sometimes, not always.) NGDP declines cause recessions, due to sticky wages.

NGDP targeting does not make credit bubbles more likely.

Sourcreamus, Consider a world where everyone has to take aspirin every day, it’s just a question of how much. Then the wrong dose could cause problems. We have no choice as to whether to “use monetary policy,” unless we plan to drop money and adopt barter.

Barry "The Economy" Soetoro

Mar 13 2014 at 3:06pm

If you think QE is a good thing and you’re advocating it here for when rates are at 0%, can you explain to me why it is better to buy the assets of the rich (bonds) and enrich them further, as opposed to sending checks to everyone equally?

TravisV

Mar 13 2014 at 3:16pm

Another key point that needs more emphasis: the degree of the FOMC’s comfort with “unconventional monetary policy.”

In late 2008, the Fed funds rate hit 0%. Since the FOMC was uncomfortable with “unconventional monetary policy,” the markets crashed.

Beginning in March 2009 and ever since, the Fed has become more and more and more and more comfortable with “unconventional monetary policy.” As a result, asset prices are far higher.

Another point: in the event of a crisis, the Fed will be far more comfortable with “unconventional monetary policy” than it was in late 2008. Therefore, any fall in employment and stock prices is likely to be far smaller than what happened in 2008 and 2009.

In late 2008 and early 2009, the Fed was rendered mute. It was extremely hard to predict the future actions of the Fed. If another crisis happens, it will be far more predictable and aggressive with forward guidance……

Dan W.

Mar 13 2014 at 4:18pm

Scott,

I would appreciate greater elaboration from you on how you expect NGDPLT to work when a credit bubble deflates.

My understanding of NGDPLT math is that when a credit bubble pops the Fed will create inflation to make up for the loss in economic output. This invariably means that the central bank will intervene in the market to soften the fall in asset values against which bad loans were made.

Do you dispute this?

Rational expectations say that investors will incorporate this assumption of reduced losses into their models. Consequently, all things being equal NGDPLT will increase financial risk and increase the chance of even greater credit bubbles.

Do you dispute this?

If not how do you expect investors to behave if there is great confidence in NGDPLT policy?

Andrew_M_Garland

Mar 13 2014 at 5:17pm

Consider the type of real science which can predict what will happen, and so is suited to guide policy. It is not primarily up to the reader to find the evidence which supports and contradicts the proposed theory. In real science, the theorist examines all of that, especially the contradictory evidence.

The late particle physicist Richard Feynman was a plain-spoken genius. This speech considers why we continue to not know the truth about many things, hundreds of years after people discovered how to do good science. An enjoyable must-read.

Cargo Cult Science

1974 by Richard P. Feynman – Commencement speech at The California Institute of Technology

=== ===

[edited] Details that could throw doubt on your interpretation must be given, if you know them. You must do the best you can to explain them, if you know anything at all wrong or possibly wrong.

If you make a theory, for example, and advertise it, or put it out, then you must also put down all the facts that disagree with it, as well as those that agree with it.

There is also a more subtle problem. When you have put a lot of ideas together to make an elaborate theory, you want to make sure, when explaining what it fits, that those things it fits are not just the things that gave you the idea for the theory, but that the finished theory makes something else come out right, in addition.

=== ===

Prediction is everything, and it must work more than once. Explaining everything after the fact is merely making up complicated stories.

Feynman says that real science is a method for discovering facts about our world, and it requires bending over backwards not to fool others, and especially not to fool oneself. He notes it is particularly easy to fool oneself, and so requires the greatest dilligence and openness to criticism and disproof to avoid being that fool.

The complicated theorizing of New (and old) Keynesianism is a lot of story telling combined with math models which have not been shown by experience to predict anything. Then, these stories are presented, without being tested against the known supporting and contradictory evidence. It isn’t science, and it is not reliable. Yet, it is used to promote and justify massive experiments on the lives of the peasants. These experiments just happen to deliver massive resources to politicians for distribution to themselves and their friends.

–

The rule in medicine is “First do no harm”. This is the reluctant position of doctors. They understand from hundreds of years of experience that it is far easier to make things worse than to make them better. People are medically complicated.

This is not the position of public economists, who pose this or that policy by making up stories about what is causing what. They just don’t know, but they are willing to guess.

EasyOpinions.blogspot.com

Scott Sumner

Mar 14 2014 at 9:36am

Barry, In general, the more bonds the Fed buys the higher the inflation rate. The higher the inflation rate the higher the level of nominal interest rates. the higher the level of nominal interest rates the lower the price of bonds. So I don’t agree that QE usually helps bondholders. It may on occasion, but that is the exception. Having said that, I favor NGDPLT, which in my view would have made QE unnecessary.

Travis, Good point.

Dan, I don’t believe in bubbles. But let’s say I’m wrong. If a bubble ends, then NGDP level targeting would keep NGDP growing at a stable rate. In most cases RGDP would not fall. If it did fall slightly, then inflation would rise slightly. But of course the long run rate of inflation is no different under NGDPLT or inflation targeting.

Under my plan the central bank does not “intervene” any more than under any other proposed Fed policy, so that assertion is inaccurate.

I don’t understand your final point. Yes, if you have fire insurance on homes, more people will want to buy homes, as they will be less risky. Ditto for sound monetary policy. So the fundamental value of a home might be higher. But that does not have anything to do with prices rising above fundamental values, which is how bubbles are defined.

Andrew, “First do no harm” is a useful maxim, but doesn’t tell us what sort of monetary regime we should have.

Roberto

Mar 14 2014 at 10:20pm

I think the 2008 recession was caused by the 2084 rate hike by 2%. Looks like the Fed will never learn!

Dustin

Mar 16 2014 at 11:24am

Scott

Perhaps this has already been covered, but I get very confused by the ‘decrease of NGDP causes recession’; often I see the decrease of NGDP is the recession.

Is it a question of timing… for example, NGDP begins falling, and due to wage stickiness / poor monetary policy, a recession ensues and NGDP continues falling?

In the above case, the initial decrease of NGDP causes the recession while the continued fall in NGDP reflects the recession.

Jerry

Mar 18 2014 at 12:44am

Off topic. I’ve been enjoying your blog for a while and I’m glad your guest blogging on this site. I know when you came aboard the hope was you’d share some of your monetary insights to a different audience. However, as a regular reader of your MI blog and econlog, I’m really hoping you can diverge off onto other topics you blog less about at MI. Thank you of always saying things in an understandable and intelligent way!

Comments are closed.