I usually start off my PowerPoint presentations as follows:

“Tell me,” the great twentieth-century philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once asked a friend, “why do people always say it was natural for man to assume that the sun went around the Earth rather than that the Earth was rotating?” His friend replied, “Well, obviously because it just looks as though the Sun is going around the Earth.” Wittgenstein responded, “Well, what would it have looked like if it had looked as though the Earth was rotating?”

Then I explain how the crisis of 2008 wasn’t what most people (on both sides of the ideological spectrum) assume it was. I end up with this slide:

Wittgenstein: Tell me, why do people always say it’s natural to assume the Great Recession was caused by the financial crisis of 2008?

Friend: Well, obviously because it looks as though the Great Recession was caused by the financial crisis of 2008.

Wittgenstein: Well, what would it have looked like if it looked as though it had been caused by Fed and ECB policy errors, which allowed nominal GDP to fall at the sharpest rate since 1938, especially during a time when banks were already stressed by the subprime fiasco, and when the resources for repaying nominal debts come from nominal income?

Where else can we apply this way of thinking? I can think of at least 5 more examples, and would appreciate any other suggestions.

1. What would it look like if it looked as though interest rates fell for some reason other than the Fed cutting interest rates with an expansionary monetary policy?

2. What would it look like if it looked as though there were no asset price bubbles?

3. What would it look like if it looked as though no one was smart enough to beat the market?

4. What would it look like if it looked as though a financial crisis was caused by FDIC-created moral hazard?

5. What would it look like if it looked like an economic catastrophe in a capitalist economy was not caused by unregulated capitalism?

For case #1, August 2007 to May 2008 will do just fine. The Fed did not inject any new money into the economy. The base was level at about $855 to $860 billion. Interest rates fell from 5% to 2%, but not because of the “liquidity effect” associated with an expansionary monetary policy. Instead, market interest rates fell for the exact same reason they often fell before 1913, i.e. before the Fed was created. Market interest rates fell because of a decline in the demand for credit. The Fed simply adjusted its official target rate to correspond to those falling market rates. The Fed did nothing to cause lower interest rates. And yet if you polled economists I’d guess at least 90% would say that rates fell because the Fed “eased” policy. Most economists probably think we fell into recession in December 2007 because velocity fell, whereas it was because the Fed suddenly stopped increasing the base—base velocity actually rose 1.6% between August 2007 and May 2008. Why do so many people think the recession was triggered by a fall in velocity? Because the Fed was rapidly cutting rates (so they think), and hence the money supply must have been increasing.

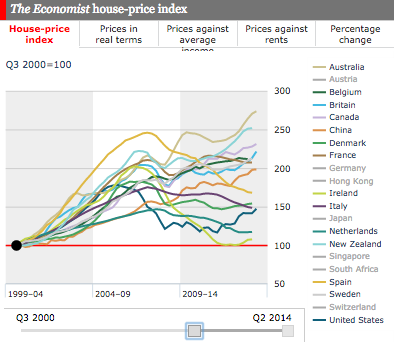

2. What would it look like if there were no asset bubbles? If prices rose sharply in an asset market, then from that point forward prices would be equally likely to rise further, level off, or fall back. And that’s exactly what happened to the global housing market in the first 14 years of this century. Prices rose sharply in most markets from 2000 to 2006, and then moved randomly after the sharp run-up. Many markets saw further appreciation. Many saw prices level off, and many saw prices fall. Thus the global housing market in the early 2000s looks exactly like a market would look if bubbles do not exist. And yet may people assume it somehow proves the existence of bubbles.

3. If no one was smart enough to beat the market, then 500,000 of each million investors would outperform the market average during any given year, 250,000 would outperform for two consecutive years, 125,000 for three consecutive years, and 1 in a million would outperform in 20 consecutive years. This may not be precisely what we observe, but it’s pretty close. In other words, if no one were smart enough to beat the market, then we’d expect to observe a very small number of investors such as Warren Buffett. And we do.

4. Moral hazard works in very subtle ways. Suppose someone loaned you $30 million dollars for a week. But then you had to repay the loan, unless you had lost it all in a casino. What would you do? One option would be to put $1 million on each of numbers 1 through 30 in roulette. There’s a pretty good chance you’d win $35 million. After repaying the loan you’d be $5 million ahead. In 8 cases out of 38 you’d lose on your bet, and be unable to repay the loan. That basically explains the 1980s S&L crisis, and also the more recent banking crisis. Most of the time the bettor wins, and most of the time banks making risky loans come out ahead. But what would it look like if they did not come out ahead? It would look like the specific factors that lead to a bad outcome on that particular occasion (people too naive to know that housing prices sometimes fall, government policies, evil bankers–pick your favorite villain) had caused the crisis. After all, those seemed to be the proximate cause, and FDIC was generating moral hazard in other decades, where things did not go poorly. So why this time?

Bad luck? I know that’s not very satisfying, but what would be your explanation if you put $1 million dollars on each of numbers 1 through 30, and the bouncing ball landed on #34? Would you blame the evil casino? When moral hazard creates financial crises, it never looks like moral hazard is creating financial crises. I’ll bet most people could not even envision in their mind’s eye what a moral hazard-caused financial crisis looked like.

5. The last one is directed at (American) liberals, who have a sort of knee-jerk reaction that “free market fundamentalism” is to blame for any crisis in a capitalist economy. I’d ask them to consider this question: What would a crisis in a capitalist economy look like if it looked as though it was caused by the indirect effects of well-intentioned government regulations? I spent the years 1977 through 1980 at the University of Chicago, being provided with hundreds of answers to that question.

READER COMMENTS

JD Bryant

Feb 11 2015 at 10:01am

I would love to see some of those answers you to your question on number 5.

Dan W.

Feb 11 2015 at 10:13am

From July 2007 to July 2008 the CPI increased at a 5.6% annualized rate. What would have been the CPI if monetary policy had been looser? How would the Federal Reserve have justified to the politicians measures that would appear to increase inflation even more?

Philo

Feb 11 2015 at 10:35am

“I’ll bet most people could not even envision in their mind’s eye what a moral hazard-caused financial crisis looked like.” Well, they could if you patiently explained it to them and they paid attention. But some possible explanations of phenomena lack *a priori* salience, and it is the salient ones that will be accepted by most people.

Philo

Feb 11 2015 at 10:42am

A great post. But I don’t like to see talk of “well-intentioned government regulations.” Whose intentions are being praised? Some of the supporters of a regulation will be public-spirited, but some will be selfish bastards who simply see that the regulation serves their interests, the public be damned!

Kenneth Duda

Feb 11 2015 at 11:24am

Great post, Scott. I could not agree more.

In running my software department, I avoid imposing well-intentioned rules on software engineers, because I’ve seen first hand the crazy behaviors you get from people trying to simultaneously do the right thing and also comply with well-intentioned rules. I don’t know the answer at the level of national banking, but for a high-powered software team, it’s easy. Judgment trumps process every time.

-Ken

Scott Sumner

Feb 11 2015 at 11:47am

Dan, Even higher. And that’s a good point–it points to the problem with inflation targeting. NGDP growth was just 1.67% (2.3% annualized) over that 9 month period. NGDP growth is what matters, not inflation, or should I say “inflation” as I have zero confidence that the government is measuring anything coherent.

One way that we know NGDP was the better indicator is that we went into deflation in 2009, and since 2008 inflation has run well below the Fed’s target.

Philo, Perhaps I should have said “even well intentioned regulations” as I agree that many (most?) regulations reflect special interest politics.

Thanks Ken.

Andrew_FL

Feb 11 2015 at 12:57pm

I don’t see how housing prices outside the US are relevant to whether there was a housing bubble in the US caused by US policies specifically.

A better response on 5 is that something which does not exist, cannot cause anything, and therefore unregulated capitalism cannot be responsible for any crisis, since there was no unregulated capitalism.

AD

Feb 11 2015 at 1:58pm

Couldn’t the Fed not increasing the base be the result of increased demand for money?

Levi Russell

Feb 11 2015 at 3:20pm

“For case #1, August 2007 to May 2008 will do just fine. The Fed did not inject any new money into the economy. The base was level at about $855 to $860 billion. Interest rates fell from 5% to 2%, but not because of the “liquidity effect” associated with an expansionary monetary policy. Instead, market interest rates fell for the exact same reason they often fell before 1913, i.e. before the Fed was created. Market interest rates fell because of a decline in the demand for credit.”

Let’s have a look at the data:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=10ug

The base is falling (slightly) before the recession and clearly increasing after the onset of the recession. Even if you cut out the December 07 value, it’s pretty obvious. Rates fell from 5% to 4% just before the recession started and from 4% to 2% after. So most of the decline happened when the base was increasing.

And even if the base didn’t increase much, M2 did. You might be able to argue that the increase in M2 had nothing at all to do with the Fed, but I don’t see how this is evidence of falling demand.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=10uo

Andrew_FL

Feb 11 2015 at 4:21pm

It actually seems to me we get nowhere looking at any money aggregate because we leave velocity out of the story entirely doing that.

For example, during August ’07 to May ’08, money in the broadest sense, properly weighted (Divisia’s M4) increased about 6%. It contracted during October ’08 to June ’10 by about 9%. The timing is about right to exacerbate the recession, but not right to cause the recession. For that you’d need an expectations story where the market had reason to believe M4 would contract when it did.

M4- tells a story that could push back the start of the money contraction a bit, but again these occur after the recession starts. Was 2007 just Friedman’s “Garden Variety Recession” turned into the Cabbage Eating Mississippi Monster?

Mike M

Feb 11 2015 at 8:01pm

What would it look like if it looked like Republicans oppose Obama’s policies not because Republicans are racists, but because they actually disagree with his policies?

Mark Cancellieri

Feb 12 2015 at 8:22am

Great article.

I have a question:

What would Fed and ECB policy have looked like if it hadn’t “allowed nominal GDP to fall at the sharpest rate since 1938”?

Also, regarding Item #3, I suggest reading:

The Superinvestors of Graham-and-Doddsville by Warren Buffett

http://www8.gsb.columbia.edu/rtfiles/cbs/hermes/Buffett1984.pdf

Buffett discusses the idea of superior investment results being the result of lucky coin flippers.

Floccina

Feb 12 2015 at 9:06am

What would it look like if it was better options for women (a form of wealth) than staying married caused the rise in divorce rather than inequality causing divorce?

Also:

All thinks are relative, the universe rotates around where ever you are. 🙂

TallDave

Feb 12 2015 at 10:11am

Excellent post, particularly #4, which I’ve tried to express before but never managed with such perspicuity.

gwern

Feb 12 2015 at 12:18pm

Is it just me, or does the Wittgenstein story actually say the opposite of how it’s being used here when you read the full story? Here’s how I remember it (from Anscombe’s Introduction):

Exactly. We predict that we would be dizzy if the earth spun on its axis rather than stayed still, our folk physics say, in the same way we would be dizzzy if we were spun around anything else.

(In this case, mechanics does succeed in patching up the falsifying observations by some complex and extremely counterintuitive rules about motion and inertia which even physics students will get wrong when asked about common fallacies – see Hestenes’s quiz for diagnosing belief in folk-physics – but Galilean/Newtonian mechanics is correct despite the counterintuitiveness, not because of the counterintuitiveness.)

Scott Sumner

Feb 12 2015 at 3:02pm

Andrew, That was not my claim. I asked what it would look like if there were no bubbles. And it would look like the results we saw in actual real world housing markets. I never said this proved there were no bubbles.

AD, No, money demand was declining.

Levi, M2 has no relevance to my argument, I’m not making a monetarist point. Monetarists are the only people who care about M2.

Regarding the base data, it is very volatile at high frequencies. Nonetheless I predict if you asked the average economist why rates fell from 5% to 2% over that nine month period, they’d say the Fed injected money into the economy. Which is false.

Andrew, The whole point of market monetarism is to add velocity to the equation, so I agree with you there.

Mike, Good one.

Mark, If they had kept NGDP growing at 5% I suspect interest rates would have been above zero.

Floccina, Good one. Perhaps that’s why divorce seems to have fallen among wealthier families and risen among low income families where men struggle to earn a living?

Thanks TallDave.

gwern, I’m not certain that that interpretation is actually different. But I hope you are right, in which case I can re-name it “the Sumner test.” 🙂

What do others think?

Andrew_FL

Feb 12 2015 at 3:47pm

@Scott Sumner-Yes, sorry, I meant that (mostly) as a response to Levi’s comment. Of course, Market Monetarists look at NGDP or similar measures, which account for velocity, instead of any particular money aggregate.

Gizzard

Feb 12 2015 at 3:50pm

Nice little sleight of hand there Scott

“Wittgenstein: Tell me, why do people always say it’s natural to assume the Great Recession was caused by the financial crisis of 2008?

Friend: Well, obviously because it looks as though the Great Recession was caused by the financial crisis of 2008.

Wittgenstein: Well, what would it have looked like if it looked as though it had been caused by Fed and ECB policy errors, which allowed nominal GDP to fall at the sharpest rate since 1938, especially during a time when banks were already stressed by the subprime fiasco, and when the resources for repaying nominal debts come from nominal income?”

You should have asked the question what would it have looked like if the financial crisis were caused by the great recession? Which you are sort of doing but only because you think Fed policies dictate the state of the economy rather than react to.

Ill ask what would it look like if the Fed policy errors were caused by not seeing a recession, until it became a banking crisis and then the Fed thought by fixing banks you could fix the recession? It would look like the last 6+ years.

Lorenzo from Oz

Feb 12 2015 at 8:01pm

Andrew_FL: “I don’t see how housing prices outside the US are relevant to whether there was a housing bubble in the US caused by US policies specifically.”

There is no single housing market in the US, there are hundreds. Some of which had very pronounced booms and busts and some did not. That differentiated pattern demonstrates that monetary policy does not “cause” housing booms and busts.

Krugman on Zoned Zone and Flatland is good on this.

Levi Russell

Feb 12 2015 at 11:56pm

Andrew,

Of course there’s an expectations element to all this. That’s why so many in the financial sector spend their (high opportunity cost) time trying to figure out what the Fed is going to do. That’s why, since Greenspan, Fed chairpersons have been so vague when they address the public. Well before QE3 actually ended, the dollar started to rise. I’m not saying it explains 100% of the month-over-month movements in the dollar since last summer. It doesn’t have to in order for me to say there’s a causal relationship.

Andrew_FL

Feb 13 2015 at 6:25am

@Lorenzo from Oz-I’m sorry that makes absolutely no sense whatsoever to me. Like it would be to say monetary policy didn’t cause the great recession because in some places, the recession was much worse than in other places. Huh?

J Mann

Feb 13 2015 at 11:28am

Tom Stoppard popularized this quote in Jumpers, where he took Scott’s position, although it might have been more for the joke than as a serious philosophical point.

From what I understand, Jumpers is a domestic farce that plays around with relativism a lot. At one point, the characters discuss the Wittgenstein-Anscombe quote. Later, the main character has a discussion with a doctor who may or may not be having an affair with the character’s wife. He’s stumped by “everything you’e doing makes it look as if . . . ” versus “what would it look like if I were doing a dermatological examination?”

As to the underlying quote, I can’t figure it out. I think the key is what meaning Anscombe ultimately ascribed to “it looks like it is”, but I’m not sure what she means to imply about that.

Scott Sumner

Feb 13 2015 at 11:55am

Thanks for clarifying that Andrew.

Gizzard, You said:

“Ill ask what would it look like if the Fed policy errors were caused by not seeing a recession, until it became a banking crisis and then the Fed thought by fixing banks you could fix the recession? It would look like the last 6+ years.”

That’s true, but there are alternative policy regimes where the “recognition lag” does much less damage, such as level targeting.

J Mann, Thanks for that information.

Comments are closed.