When I moved to Boston in 1982, no one talked about the declining share of national income going to labor. Or increasing income inequality. Now these are the hottest topics in economics. Much of the discussion seems to implicitly suggest that there is some sort of “mystery” to be explained. Perhaps corporations are getting better at lobbying in Washington. Or maybe there is cultural change that makes CEOs bolder in demanding high pay.

I find those sorts of explanations to be unsatisfactory. Too vague. Let’s go back to my move to Boston. The city I moved to in 1982 was radically different from the Boston of today, even though superficially it doesn’t look all that much different. It has not gone through the sort of radical physical transformation that you see in places like Shanghai, or even Austin, Texas. But nonetheless Boston is radically different, and has changed in ways that seem to correspond quite closely to the growing inequality in America.

I’m going to suggest that maybe there is no big mystery to explain. I won’t present any new ideas, but rather bundle together some innovative work done by others. It seems to me that the economy has changed in such a way that it would be surprising if the labor share of income had not fallen. Indeed perhaps the real surprise is that the ratio has not fallen by even more.

I believe that major societal changes don’t just happen randomly, they have causes. Here are three reasons that others have pointed to:

1. The growing importance of rents in residential real estate.

2. The vast upsurge in the share of corporate assets that are “intangible.”

3. The huge growth in the complexity of regulation, which favors large firms.

Kevin Erdmann did some very important posts on the share of income going to capital, which haven’t gotten anywhere near the attention they deserve. Here are a few excerpts, but read his whole series of posts:

We start with Profit (the blue line at the bottom). I have extended the time frame further back. The green line represents all returns to corporate capital, both to debt and equity. The debt portion peaked in the early 1980’s when corporate leverage was at its highest. When we make this correction, we find that corporate returns to capital have been flat for 40 or 50 years. If we add in proprietors’ income, we find that returns to capital have been flat or declining for a century. From 1929 to about 1985, there was a trend of profit claims moving from proprietors to creditors. From 1985 to the present, there was a trend of profit claims moving from creditors to equity owners. But, there is no trend of increasing total returns to capital over the past 30 years.

So in recent decades the rising equity income is offset by falling interest income, leaving total income to the corporate sector fairly stable, as a share of GDP. But then why is labor losing out? It turns out that more income is going to the residential real estate industry, but it’s implicit income from rents:

First, this is a little tricky, because 60% of American households own their homes. So, in effect, this is a measure of rent we are paying ourselves. Or, put differently, this is a measure of the income share we capture because home ownership tends to provide excess returns.

The trend in Compensation has dropped from about 57% in 1970 to about 53% – a 4% drop. But, the trend in Rent + Compensation has dropped from about 59% to 57%. Rental income explains about half the drop in Compensation Share, and in fact, accounts for more than all of the drop in Compensation Share since the previous low point in 2006.

To the extent that Rental Income supplements Compensation, this income is probably distributed mostly to middle and upper-middle class households. So, both the level and the distribution of household Compensation Share are probably helped by reducing excess returns to Rental Income.

Boston has extremely tight regulations on building, and a strong high tech economy. Put the two together and you have extremely high rents. And it wasn’t like that when I moved to Boston in 1982. They had lost a lot of their older industries, and people were moving away to the Sunbelt. Rents were not all that high.

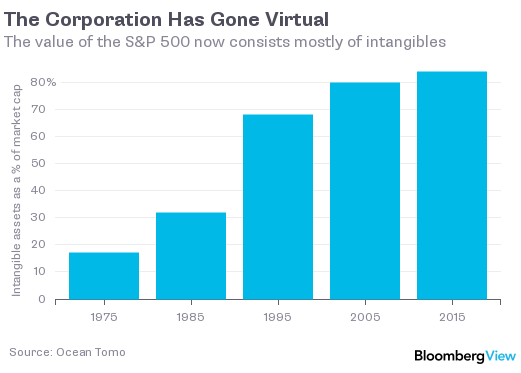

What about corporations? We all know that the capital-intensive businesses of yesteryear like GM and US steel are an increasingly small share of the US economy. But until I saw this post by Justin Fox I had no idea how dramatic the transformation had been since 1975:

The rise of companies like Apple, Facebook and Uber affect the economy in two ways. Intellectual property rights create more monopoly power than manufacturers of TVs and refrigerators had back in the 1960s, and this boosts corporate profits. In addition, the individuals with the creative ideas and/or the financiers who picked the winners in the high tech race can make much larger personal incomes than a CEO at an appliance maker in the 1960s. How hard is it to figure out how to make washing machines? How hard is it to figure out the next WhatsApp? These are totally different skills.

However, I’d guess that it’s not just about high tech. We’ve also seen companies like Starbucks do increasingly well against the local corner coffee shop. There could be lots of reasons for this, but one might be the rapid growth in regulations. When regulations are highly complex, there are enormous economies of scale in dealing with the complexities. This favors larger firms. And as this article at Free Exchange points out, anything that favors the growth of larger firms tends to increase inequality:

The standard explanation says that technology plays a big role: modern economies require more skilled workers, raising the pay premium they can demand. A new paper* by Holger Mueller, Elena Simintzi and Paige Ouimet adds a new and intriguing wrinkle to this: the rising size of the average firm. Economists have long recognised that economies of scale allow workers at bigger firms to be more productive than those at smaller ones. That, in turn, allows the bigger firms to pay higher wages. This should not, in theory, cause a rise in inequality. If the chief executive and cleaner at a larger firm are both paid 10% more than their counterparts at a small firm, the ratio between their wages–and thus the overall level of inequality–should remain the same.

But the paper shows that the benefits of scale are not shared equally among all workers. Using data on wages at British firms, they divide workers into nine groups according to how skilled they are. Over time, they find that the proportional difference in wages between the groups grows as firms get bigger. This trend is driven entirely by a rising gap between wages at the top compared with the middle and bottom of the distribution. As the authors note, this is very similar to the trend in income inequality in America and Britain as a whole since the 1990s, when pay for low and median earners began to stagnate (see chart).

What do all three of these explanations have in common? Regulations. Building restrictions are increasing rental income as a share of national income. Intellectual property rights are barriers to entry that tend to create a winner-take-all situation (although other factors like network effects also play a role). And other types of regulations (financial, human resources, etc.) are especially burdensome for small firms, and this favors the growth of inequality-intensive large firms.

All of these changes have hit Boston in a big way since 1982. Boston has itself become more unequal, and it’s also moved further ahead of the American average income. Building restrictions here are almost comically excessive (which means that living standards aren’t that high, despite the high incomes). Industry is dominated by knowledge-intensive sectors.

I would not argue that these forces explain everything about inequality. My first full-time job at St. Bonaventure (assistant professor) paid $19,300 in 1981. I’d guess that was less that autoworkers made back then. Today econ professors start at almost $100,000 at some schools, whereas newly hired autoworkers are forced to accept much lower pay than the more senior members of the UAW. Technology and trade have widened the gap between blue-collar workers and professionals. But two of the types of inequality that are most frequently discussed are very much impacted by these trends; the falling share of national income going to labor, and the rising share of labor income going to the top 1%.

Given the three factors cited above, the only mystery I can see is why the inequality hasn’t gotten even greater.

Update: I forget to mention Matt Rognlie’s excellent work in this area. He makes some of the same points about rental income that Erdmann made.

Update#2: I also forget to mention Scott Winship.

READER COMMENTS

E. Harding

Mar 28 2015 at 1:00pm

That’s a great graph, Scott, and I think it explains a lot about the rise of the incomes of the top 1%. And blue-collar labor has, indeed, fallen mightily:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=15AP

And you’re right about young auto workers earning more than you in the early 1980s: that was back when the cities in America with the highest wages for young people were Flint, Detroit, and Chicago:

https://www.aei.org/publication/new-census-bureau-data-young-adults-provide-fascinating-insights-forces-creative-destruction/

As Peter Thiel once pointed out, PayPal under his management had about as many employees as a typical small restaurant, but had much larger revenues. This can only exacerbate income inequality.

Kevin Erdmann

Mar 28 2015 at 1:25pm

Scott, I was surprised to find that this rental income is not skewed to higher income households.

Also, imputed rent is not usually included in wage and income measures, which explains part of the lag between incomes and total production as imputed rent becomes a larger portion of consumption.

Kevin Erdmann

Mar 28 2015 at 2:04pm

The fact that imputed rent is not included in household earnings also probably distorts debt – income ratios as ownership, rents and nominal home prices rise. Also because homes are real assets but mortgages are generally nominal, the inflation premium of the mortgage interest is treated as income to financial corporations when it is really savings by the household, in real terms.

Kevin Erdmann

Mar 28 2015 at 2:30pm

At the risk of monopolizing the comments, here was a post I did about housing and Picketty.

Mark V Anderson

Mar 28 2015 at 5:39pm

I am very skeptical about that graph. I wonder how much of the increase is due to goodwill. Goodwill is simply the plug value of the value of a business over its book value when it gets acquired. Companies that don’t get acquired still have this implicit goodwill, but it never shows up on the books. So an increase in goodwill mostly indicates that more businesses are being acquired, not that the value has changed. Also the goodwill could as easily be extra valuations of tangible property as that of intangibles.

Also, the value of intellectual property such as patents and trademarks do not show up on a company’s balance sheet unless either the company or the property itself is acquired. Again, an increase on the balance sheet indicates an increase in buying and selling, not an increase in the value of the property itself.

I clicked through several of the links to try to determine the source of the numbers of the graph. I wasn’t able to find the source, but I suspect they come from the balance sheets of the companies. As I discussed above, intangible asset values can mean very different things on different balance sheets, so aggregating them results in only gibberish.

I imagine that intellectual property is indeed an increasingly large proportion of the value of businesses over a few decades ago, but aggregating S&P 500 balance sheets proves nothing.

Michael Byrnes

Mar 28 2015 at 7:33pm

A minor nitpick:

“We’ve also seen companies like Starbucks do increasingly well against the local corner coffee shop.”

Is this really true? I mean, it is certainly true that Starbucks has done extremely well. But I would venture to guess that, on the whole, local corner coffee shops are also doing much better today than before the rise of Starbucks.

Scott Sumner

Mar 28 2015 at 10:14pm

E. Harding, Good point. I used to visit Michigan a lot when I was young (in the 1960s)–the state seemed very prosperous.

Kevin, Very interesting observation. And that’s why I differentiate between income equality and the changing share of income going to capital vs. labor.

Scott Winship also did work explaining the difference between GDP growth and real wage growth, which makes some of these points:

http://www.forbes.com/sites/scottwinship/2014/12/16/workers-get-the-same-slice-of-the-pie-as-they-always-have/

Mark, Interesting. I’d guess a number of factors are involved, and I’m not qualified to speculate as to their relative importance. But as you say, regardless of the measurement issues, intellectual property seems increasingly important.

Michael, I guess I meant that the share of coffee shops that are part of big chains seems to have risen, but I don’t have any hard numbers.

3rdMoment

Mar 29 2015 at 1:30am

@ Mark V. Anderson,

I think you are confused by the poorly labeled graph. All it shows is the share of market cap that is NOT accounted for by tangible book value.

In other words, you take net tangible book value (excluding goodwill and other intangibles, but including cash and financial assets), divide by market cap, then subtract the result from 100%.

You can see the source here, where it’s more clearly labeled:

http://www.oceantomo.com/blog/2015/03-05-ocean-tomo-2015-intangible-asset-market-value/

mbka

Mar 29 2015 at 10:34am

Correct me if I’m wrong, but either way you read the graph, it gives yet another reason why Piketty is just completely on the wrong track. If (a) returns on total capital rise but the share of intangible capital are rising fast, while (b) one assumes that all returns are returns on tangible capital, as Piketty seems to do, then these same returns are vastly overestimated. Or does he correct for that?

gmm

Mar 29 2015 at 11:33am

As someone who works at a big software company, I don’t think we rely heavily on intellectual property rights. Most of our software is delivered as a service, and we rely on secrecy to prevent people from copying it.

And for a lot of things, we don’t care about it being copied, so we give it away (open source).

Robert Schadler

Mar 29 2015 at 1:13pm

1. (Re: Henderson): It seems easy, especially among enthusiasts, to gloss over that Smith is more emphatic about thrift than are more free market advocates these days. A widespread theme — but not absolute. Going into debt to buy food necessary to stay alive might well be an exception. Buying a house, especially in the U.S. under recent conditions might well be another special case. But likely he’d see a need for some basic shelter as well as food. A house is only part a consumable; part an investment.

And would one be wrong to think that the “regulations” in effect here skew things in favor of both home builders and home buyers? An aspect of crony capitalism? And thrift is often how when gets the down payment.

2. (Re: Sumner) The Sumner comment seems brilliant.

a. The broad movement toward “non-tangible resources” (no less an oxymoron than “human capital”) needs far more analysis that neoclassical economists have given it. And likely economists as a whole.

b. Yes, regulations overwhelming benefit large firms over small ones. One might well add the drive for greater regulations as an aspect of Smith’s collusion by businessmen or a clever form of crony capitalism. The big firms, with power lobbying, skew the rules of business to favor themselves.

The one counter trend might be that small businesses may not follow regulations as extensively as the big ones. If they did, they might well not continue to exist (which would, of course, suit the big firms just fine). Often the entrepreneurial small firm, especially those that focus on “intellectual capital” survive and grow because, as is usually, the government is slow, and so it often fails to regulate the entrepreneurial activity until it is too late to squash it in its crib.

Vivian Darkbloom

Mar 29 2015 at 4:21pm

What has changed since 1982?

1. This post may suggest that most (80 percent) of the value of the S&P 500 consists of intellectual property such as patents, copyrights and trademarks. But, as pointed out in the Justin Fox article, a great deal of the value of corporations not attributable to tangible assets is the result of increased price/earnings multiples. This could also be the result of lower earnings discounts due to lower interest rates. From an accounting point of view, the residual value from the increased multiple would be attributable to “goodwill” for any purchaser. This is, of course, a form of “intangible”, (gmm., I think, addressed the same issue in the comment above); however, it is quite relevant to the remark “Intellectual property rights create more monopoly power than manufacturers of TVs and refrigerators had back in the 1960s, and this boosts corporate profits.” “Goodwill”, as a residual value, is not a “property right” in the sense that is not protected by law. Quite the contrary, as any technology firm would likely tell you, “goodwill” is quite fragile and transitory. It can evaporate very, very quickly and shift from one corporation to another.

2. Globalization. I’m surprised this was not mentioned because it is a major contributing factor to the shift from tangible assets to intangible assets for US corporations in the S&P 500 Index. US corporations have been able, more than corporations in any other jurisdiction, to leverage their intangible assets (creating goodwill) due to the much more expansive markets available to them today than in 1982. Another effect of this has been that much of the tangible assets (e.g., plant and equipment) have been relocated from the United States to corporations headquartered in places such as China. I’m convinced that a great deal of US inequality is the result of globalisation where top earners leverage their ideas globally; whereas, US laborers have lost ground due to global labor competition.

3. The S&P 500 Index comprises a major portion of US corporate value ; however, it does not represent the total value of all corporate assets in the US. A better indicia of the trend cited here would take into account total market value and not just this particular index. Has the S&P 500 Index stolen some of the technology value from, say, the NASDAQ since 1982? Or would including the NASDAQ in the chart above actually demonstrate an even more dramatic shift to intangibles?

Scott Sumner

Mar 29 2015 at 7:36pm

mbka, I’m not sure, but I had assumed that Piketty’s 5% figure referred to the return on all capital, including intangible. I.e. he was looking at things like rate of return on stocks, real estate, etc.

gmm, Ok, but how would a company like Microsoft be affected if it was legal to copy their software? I had assumed its profits would decline sharply.

Robert, Good point.

Vivian,

1. Agreed. I did not mean to suggest that the 80% was all due to intellectual property rights, indeed I mentioned things like network affects. The point made by gmm also seems relevant, although I’m not enough of an expert to comment on its importance.

2. Good point about globalization and US corporate profits. I mentioned that in earlier posts, and should have mentioned it here.

Mark V Anderson

Mar 29 2015 at 8:16pm

3rd moment —

IT is true that I didn’t notice that they used market value in describing the graph, so they can’t be taking the numbers straight off the balance sheets.

But your further comment that they took tangible book value from the balance sheet and backed into intangibles value is not stated on the link. It makes sense that they might do this, but they don’t say that.

And even if so, it certainly doesn’t mean that these intangibles consist of intellectual property. It could just be that market value greatly exceeds book value, a measure of implicit goodwill. As Vivian states above.

3rdMoment

Mar 29 2015 at 8:38pm

I think people are taking too narrow a view of what constitutes “intangibles” in the figure, as I blogged here:

http://3rdmoment.blogspot.com/2015/03/whats-driving-trend-towards-intangible.html

Mark V. Anderson —

Yes, I totally agree that’s exactly what it is. The question is why has this changed so much?

Kevin Erdmann

Mar 29 2015 at 10:14pm

I suspect that a lot of this is the fast obsolescence cycle and winner take all context for many tech firms. This also leads to higher margins. The lower tangible value is probably partly explained by write offs from losing competitors, which are still effective in the total returns from past (and future) investments, but current balance sheets appear to be lower.

Vivan Darkbloom

Mar 30 2015 at 3:49am

The chart featured here and much of the discussion has been centered around whether US corporations have “gone virtual” and the extent to which their assets consist of “intangibles”

It might be useful to think of the issue in a bit different perspective: Would it not be just as accurate to say that the average US corporation on the S&P 500 has become much, much more productive than in 1982? That sounds a lot more positive!

Alfred

Mar 30 2015 at 2:54pm

Professor Sumner,

Would you happen to have a summary of these “comically excessive” regulations? As a transplant to Boston I suspect this is a completely accurate but short of reading through the BRA’s zoning code I can’t find any accessible information, especially in comparison to other cities. Could you please point me the right way?

I was recently in Toronto and was shocked to see cranes everywhere and avertisements for mass public for new condo units. I think they may build more there in a year than we have in the past 5, especially in residential housing.

Thank you

Comments are closed.