In economic theory, there is no particular reason why countries should have “balanced” current accounts. No one cares that California’s current account with the rest of the US is usually unbalanced, and often by a sizable amount. Nor should they care. Perhaps the most basic misconception is when people try to draw causal inferences from this identity:

GDP = C + I + G + (Ex – Im)

It looks like a current account surplus would boost GDP. However the current account surplus is exactly equal to (S – I), and that net foreign investment term has an equal and opposite impact on GDP. Never draw causal inferences from an identity.

People like Paul Krugman make more sophisticated arguments. They admit that in normal times current account surpluses are not a problem, but insist that everything is different at the zero bound, when there is a global demand shortfall. Ben Bernanke seems to share this view, suggesting that the world would be better off if the Germans reduced their current account surplus with a more expansionary fiscal policy and/or higher wages.

I think that’s a bad idea. Instead of criticizing the German fiscal and labor market policies, we should be criticizing their views on monetary policy and emulating their excellent policies in other areas.

Bernanke is a bit vague as to the ultimate cause of the demand deficiency that he refers to, but in the case of Europe there really can’t be any doubt—the ECB. And before anyone brings up the “zero bound” issue, recall that the eurozone has been at the zero bound for only a small percentage of the past 7 years, and indeed the ECB was raising interest rates as recently as 2011. It was tight money that caused the demand deficiency.

The ECB was a really bad idea, as the Greeks and the Germans do not belong to the same optimal currency zone. If there had to be an ECB, then running an ultra-tight monetary policy in the midst of a deep recession and massive debt crisis was a mistake of almost mind-boggling proportions (as Bernanke surely recognizes but is too polite to mention.)

But if you insist on having a euro, and then insist on having an absurdly tight monetary policy that drives NGDP lower, then the only real solution is to align your wage level to the reality of low NGDP. The Germans have done that; they’ve “balanced” their economy. The others have not.

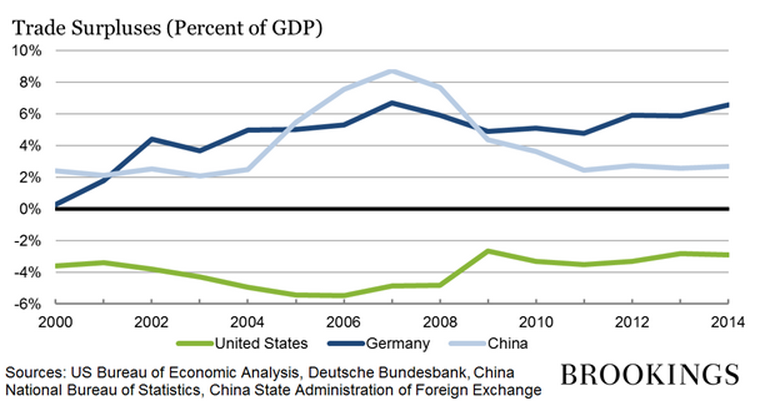

It’s interesting that Bernanke’s post provides a graph of the Germany CA surpluses, which somewhat undercuts his argument.

The surplus was in the 4% to 6% of GDP range throughout the 2002-07 period. And yet “despite” that huge surplus, Germany suffered from double-digit unemployment. The Germans fixed the problem the only way they could (given the euro) they reduced labor costs and provided low wage subsidies to get people off welfare. Unemployment fell to 4.8%. Other European countries should have done the same, but most are too left wing to do so. So they must suffer, the Greeks most of all.

There may be worse policies than right wing monetary policy combined with left wing labor market policies, but I can’t really think of any.

At this point people often make the silly argument that not all countries can run current account surpluses. Yes, but as we can see from the German case, current account surpluses have nothing to do with unemployment. All countries certainly can cut their wages to fit the lower NGDP, or much more sensibly all countries can agree to give the ECB a better mandate, such as NGDPLT, and boost NGDP to fit the wage level of the overall eurozone. (Of course many individual countries like Greece would still need major structural reforms.)

The key to success is monetary policy that stabilizes the path of NGDP (i.e. level targeting), flexible labor markets, and pro-saving fiscal policies. Always. Even at the zero bound.

Update: The US experienced a current account deficit of $410 billion in 2014. The eurozone experienced a current account surplus of 240 billion euros in 2014. Guess which region has an unemployment rate double the other region?

READER COMMENTS

Vivian Darkbloom

Apr 4 2015 at 4:34pm

“The ECB was a really bad idea, as the Greeks and the Germans do not belong to the same optimal currency zone. If there had to be an ECB…”

I doubt this is what you literally mean. It appears that you mean that the Eurozone (or the EMU second and third stages) was a bad idea, or perhaps that an expanded Eurozone to include countries such as Greece was a bad idea, or perhaps that it was a bad idea to have a Eurozone without a tighter political and fiscal union; but, not that the European Central Bank (ECB) was a bad idea. One could envision a well-functioning Eurozone (along with an ECB) with fewer members–say, Germany and the Benelux and perhaps even France where the benefits would outweigh any disadvantages. And, one could conceivably have a common currency without a Central Bank. The latter, while conceivable, probably would not be a good idea.

Gordon

Apr 4 2015 at 5:20pm

Scott, when you say that Germany has aligned its wage level to the reality of low NGDP, are you referring to how it scrapped its national minimum wage and implemented a wage subsidy? Or is there some other way that this was achieved? If the former, what are your thoughts about Germany’s reimplementation of a national minimum wage?

ThomasH

Apr 4 2015 at 7:29pm

Here is Bernanke’s policy options

1. Investment in public infrastructure. …

2. Raising the wages of German workers. …

3. Germany could increase domestic spending through targeted reforms, including for example increased tax incentives for private domestic investment; the removal of barriers to new housing construction; reforms in the retail and services sectors; and a review of financial regulations that may bias German banks to invest abroad rather than at home.

I take 2 to mean higher nominal wages through higher inflation to the extent Germany can do this withing ECB policy..

genauer

Apr 5 2015 at 4:16am

I tried to post this on Bernanke’s blog,

but they censored it. Apparently theys dont like

people correcting false claims:

There are quite a number of erroneous statements:

Instead of direct citing, the facts directly, numbered unusually in order to adjust to the text above

A. the German Current Account surplus was also high during the many years (2007 – mid 2014) of a high (defined as > 1.3 Dollar per Euro, vs. a “fair value” of about 1.15 – 1.2) Euro/Dollar FX rate

B. Germany has now substantial wage inflation of about 5% for several years in the export sector (metal worker union tariffs “IG Metall”), and the 2015 introduction of a national minimum wage, substantially higher than the US

1. Germany has very good public infrastructure (see e.g. WEF ratings) spending “a little more” within the budget discipline will not change anything noticeable for others. Germany has record low unemployment (lowest since 1982); any further “stimulus” like the low Dollar exchange rate now will force overheating.

2. private sector wage settlements are between the “Tariff partners”, Employers and Employees, hardly underrepresented with half the board seats and the mightiest unions in the world (IG METALL 2.5 million member strong and rising, please compare to a 4 times larger US population. Wage negotiation are none of the business of government, and especially not alien ones, nor other alien pressure )

3. Private domestic investment in Germany is already extremely incentivized. Larger Companies like Volkswagen enjoy 18 year interest rates of 1.3%, substantially below Zero after inflation and tax

New housing construction in Germany is no problem beyond some hot spots like Munich, which is limited by pure space restrictions of transport infrastructure. To destroy the long term livability of huge cities for some short term spending gimmick would be completely crazy.

To summarize, the idea to waste German wealth for very uneconomic things, to actually distort and destroy the right balance, in the name of some eternal Keynesian debt accumulation, is very bad advice for Germany and the world.

P.S. I can back up everything with detailed numbers (IMF WEO, OECD) links to analysis provided in other blogs

genauer

Apr 5 2015 at 4:41am

@ Gordon

Germany never had a minimum wage until this year, at least in the West.

And the introduction of the minimum wage is, although really NOBODY mentions that in public discussion, actually the necessary consequence of the wage subsidy (Hartz IV) and the freedom of movement in Europe now also for Romania and Bulgaria (with minimum wages of 1.5 Euro, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_minimum_wages_by_country)

Hartz IV was intented to force people to take up any work and any wage, if they apply for the social minimum payment (some 365 Euro + health insurance+ rent + utility + other stuff, so for a single about 800 Euros for a single)

Because if a friend of somebody (German or more likely an immigrant coming) hires people for 1 or 2 Euros, next to nothing, they then become eligible for the German social minimum, significantly better than the average wage in Romania and Bulgaria, and he does not have to look for a higher paid real job. And after a few months the immigrants becomes entitled to stay in the German welfare system forever, whether having any real job or not, or even being able to perform any

Without the minimum wage of 8.5 Euro = about 10 Dollar, the Hartz IV replacement of “Sozialhilfe” in 2003 created a lot of moral hazards between employers and employees, especially in the care giver area, speaking of unintended consequences. Employees had no incentive to ask for a higher wage, but being better off with some non-monetary benefits instead.

ThomasH

Apr 5 2015 at 6:54pm

Good news about German wage inflation this will help restore competitiveness in the South. Given the slightly crazy idea of having a monetary union, having some countries “overheating” at times is necessary to prevent others from having to deflate.

Scott Sumner

Apr 5 2015 at 7:02pm

Vivian, I see your point. I guess I should have said “this ECB” not “The ECB.” I meant the actual ECB system, open to all members of the EU that meet the convergence criteria.

Yes, a smaller eurozone might have worked, but even that’s not clear. Without the weaker members the euro would be stronger against the dollar, and France and the Netherlands would struggle even more. Austria would probably fit, as would Luxembourg.

Gordon, I don’t think they had a minimum wage. I don’t know all the details, but there was some sort of labor reforms around 2003-04 to make wages more flexible, which slowed the growth in wages, and provided low wage jobs (plus subsidy) for people on welfare.

Thomas, If they stay in the euro, then higher nominal wages imply higher real wages—and fewer jobs (if the wage increase is artificial.)

Genauer, Very interesting information—probably worth a blog post.

Andrew_M_Garland

Apr 5 2015 at 7:11pm

Sumner: “All countries certainly can cut their wages to fit the lower NGDP”

How does a country (government) do that? Does any non-totalitarian government set wages?

Even a minimumm wage law doesn’t set wages. It only adjusts statistics by eliminating people who could work for less, but not at the minimum.

Scott Sumner

Apr 5 2015 at 8:34pm

Andrew, It’s not easy, but you can make the labor market more flexible, i.e. more free market-like, and eventually wages will fall to the equilibrium.

Most European countries have all sorts of quasi-governmental controls over wages, including government enforced cartels.

genauer

Apr 6 2015 at 7:19am

1. it is kind of interesting that nobody seems to have a problem with Bernanke demanding from the German government to force private wages higher, but, like Andrew correctly ask, could only a totalitarian government setting lower wages?

2. what makes Mr Bernanke so disappointing is, that he apparently knows very little about the country, he gives unsolicited, unqualified, and self serving advice to.

The main difference is, that German(y) knows a lot about the US, the thinking, the data, the system, and Americans know very little about other countries, like Germany, but dish out plenty of advice.

3. to exercise this here with a few questions:

a) has any of you ever lived for years in a different country, becoming familiar with the social system (taxes, pension, real estate market, labor laws, social benefits)? Where would you have your information from, about e.g. Germany?

b) has any of you ever taken a closer look at the economic model of the US Central Bank (Fed) and the European ECB ? How would you describe it in one or 2 sentences. What are the key differences, and why?

c) has any of you ever read a German economics text book? Which one?

brendan riske

Apr 6 2015 at 3:19pm

Germany’s growth as wound up in Europe’s decline. The Euro is far cheaper than the deutchmark would be, which allows Germany to keep its exports high and the lowering of the interest rate boasted growth in Germany because that’s where most of the productive Euro denominated investments where. Germany will have to become more domestically focused to survive, and it cant even rely on Euro zone exports to help because of the economic decline of the rest of the union. I agree with Scott, the Euro is doomed and now we will watch it slowly unravel to counteract that imbalance.

genauer

Apr 6 2015 at 6:50pm

Brendan,

you have achieved the remarkable feat, to make in 4 sentences 7 wrong statements.

1. There is no “Europe” decline relative to the US

http://de.slideshare.net/genauer/gd-pper-capita-in-ppp-us-versus-euroarea-germany

2. The German Current account surplus was the same 6%, when the Euro was at 1.4 Dollar 2006 -2013.

3. The interest rate (also of private) invest in German is low, because the invest is not needed to a) keep up a high quality public infrastructure and b) an highly productive export sector. German corporate invest goes since decades to countries with a) the customer base, suppliers, and lower wages , like China, Brazil, Portugal. That makes us so resilient against currency rate fluctuations.

4. “to survive”, what language for a country running red hot on all 5 cylinders.

5. “rely on Eurzone” Our exports have been since many years increasing less to the Euro area (with which we have a practically balanced account), more to the rest of Europe, and the most to the outside of Europe

6. The German weakness after 2000 was not fixed by “introduzing wage subsidizes”, but by giving pressure to people being on the existing “social help”

http://de.slideshare.net/genauer/sampler-2-of-imf-2014-weo-data-plots page 2, look for the employment data after 2003 for the Germany.

You can also see there that the employment problems of France and Italy are long term structural preceding the 2008 recession.

7. The Euro will certainly not unravel, just maybe a Grexit, because everybody profits from rocket low interest rates, provided as credit (20% of our GDP in http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TARGET2 at 0.05%) and another 20% GDP guaranteed by Germany (ESM, EFSF, KfW, etc.) , please see page 7 of the above slideshare.

Can you tell me just one (non-Greek) senior politician in the EuroGroup, who complains about the German Current Account Surplus, which enables that? I only hear this from the the outside US/UK

and to add a little more to my question list:

4. Has any of you ever traded specific government bonds by him/herself? Maybe even from foreign countries ? Would you at least know how to do this in your stock account?

5. Has any of you ever solved a a differential equation (system)? Analytically or Numerically? Specific Example?

Rob in Aus

Apr 6 2015 at 8:24pm

http://blog.mpettis.com/2015/02/when-do-we-decide-that-europe-must-restructure-much-of-its-debt/

If you get a chance Scott, it is worth a read. He writes long posts but they try to substantiate all the key points of his argument.

I imagine you have significant disagreements.

genauer

Apr 7 2015 at 8:24am

“Rob in Aus”

You asked Scott, but I give you an answer too: “Never”

The idea that countries with a similar or lower debt than the US / UK (see page 3 of my http://de.slideshare.net/genauer/sampler-of-gdp-and-other-data-emphasis-on-russia or the IMF data directly, and massively lower interest rate costs for years to come (even Italy and Spain 0.7% lower than the US) would have default, but not the US, this is completely absurd.

It just shows, that the alien Michael Pettis does not know the elementary facts. He does substantiate NONE of his arguments (with numbers) because he doesn’t know them. I have not seen a single number based argument.

Further this “when do we decide”. Huugh? Since when is some unelected alien, living far away, even part of any discussion, left alone “decision”?

I spell this out so clearly because this is very typical for Anglo-Americans from economics nobel prize winners (not just Krugman, but e.g. Phelps too) over folks like Rogoff, always the same pattern, not even knowing elementary facts, no insight in the real mechanism, but lots of (false) advice.

Did any of you ever hear a German economist or politician trotting out advice to the US Government and central bank? Ever? Show me!

Although we have something quite substantially to show, see the http://de.slideshare.net/genauer/gd-pper-capita-in-ppp-us-versus-euroarea-germany again despite carrying the burden of the reintegration of Eastern Germany alone (that did cost cumulative 100% of our GDP, over 15 years and made us frugal and efficient) being since many decades the largest contributor to the EU budget, and provide the largest conventional NATO forces in Europe

How did we do it? How do we do it? Anybody interested to learn about a true success story? Or do you just want to continue to ravel in your worse economic performance and dream about how to screw up a better working model? How to be resilient against all kinds of exchange rate and oil price fluctuations, not creating any bubbles, even increasing employment from 2007 to 2009. Interested ?

Scott Sumner

Apr 7 2015 at 10:02pm

Brendan, Just to be clear, I do not think the euro is doomed, despite believing it was a bad idea. Of course it’s quite possible that Greece will leave, but on balance I think it’s more likely than not that the euro will survive, even if Greece leaves.

Rob, Yes, I often read Pettis’s blog.

Shane L

Apr 9 2015 at 8:29am

“The Germans fixed the problem the only way they could (given the euro) they reduced labor costs…”

I’m not an economist and may misunderstand this, but looking at Eurostat’s Labour Cost Index it seems that many Eurozone countries experienced declines in labour costs in the 2000s and 2010s:

http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database

Countries where labour cost change dips below zero include Greece, Croatia, Portugal, Cyprus, Ireland and France (but not Germany). I’m not certain I read this correctly but it ties in with my understanding of events in Ireland where earnings per week fell fairly consistently since 2008.

http://www.cso.ie/quicktables/GetQuickTables.aspx?FileName=EHQ03.asp&TableName=Earnings+and+Labour+Costs&StatisticalProduct=DB_EH

Jose Romeu Robazzi

Apr 9 2015 at 3:07pm

Great post, Prof. Sumner, I was very surprised to see Bernanke take on Germany this way. Germany has a democratic system, its government is popular, they are a wealthy country, they do their homework and defend their own interests. Why on earth should anybody think(or suggest) they should do otherwise?

Comments are closed.