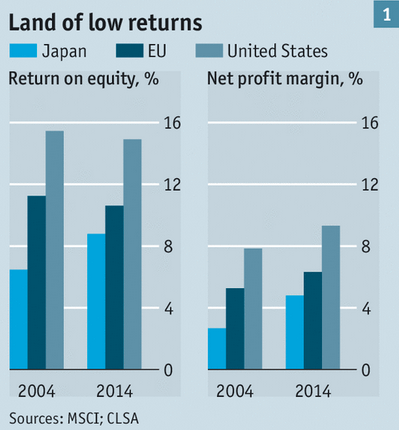

Some progressives complain that American CEOs are overpaid. They point to the fact that the spread between the highest and lowest employee in a Japanese corporation is far lower than in the US. The implication is that if only the CEOs in the US would accept smaller salaries, the shareholders would gain larger profits. In fact, as the Japanese case shows the exact opposite is far more likely. Here’s a graph from a recent article in The Economist:

The performance of Japanese corporations in recent decades has been abysmal.

Obviously there is no single factor involved, but the Economist does a nice job of explaining many of the peculiarities of the Japanese labor market, such as the lifetime employment system (which increasingly excludes younger workers), rigid promotion by rank and tenure, and fixed pay scales. Here’s one company that is beginning to change:

There is no firm that better embodies the results that reform can achieve than Hitachi. It was formerly one of Japan’s most conservative: the consummate “community” firm, at which employees and their families, and suppliers and their dependents, all took precedence over shareholders. In 2008 it notched up the largest loss on record by a Japanese manufacturer. Since then it has spun off its consumer-related businesses in flat-panel TVs, mobile phones and computer parts to refocus on selling infrastructure such as power plants and railway systems. More recently Hitachi has made efforts to change its internal culture. Last year it all but abandoned one of the central pillars of Japanese business: the seniority-wage system, in which salaries are based on age and length of service rather than on performance. The results of all this have been stellar. Its operating profits in the year to March rose by 12% to ¥600 billion ($5 billion).

Now, says Kathy Matsui of Goldman Sachs in Tokyo, stockmarket investors are all searching for the next Hitachi. Activists and private-equity firms are sensing an opening up of opportunities. Seth Fischer, an activist investor, says the government’s backing makes all the difference when it comes to shaking up firms. He is preparing to take on two industrial giants, Canon, a camera-maker, and Kyocera, an electronics and ceramics manufacturer, over their complex corporate structures.

The growing proportion of shares in Japan’s listed companies owned by foreigners (see chart 2) has undoubtedly added to the pressure on firms to change.

The traditional system was well-intentioned, but simply doesn’t work in the modern world:

Japanese firms have clung to their traditions of lifetime employment in a single workplace, and of paying and promoting people according to seniority, because they believe those traditions have merits. Indeed, they foster loyalty, and thereby encourage firms to invest in training graduates without fear of them being poached by rivals, argues Yoshito Hori, the founder of GLOBIS, a business school. However, it is no way to produce the sort of managers needed to lead modern, knowledge-based industries. “Imagine if you took managers at Apple, Google and Amazon and replaced them with people promoted on the basis of length of service rather than merit,” says Atul Goyal, an analyst at Jefferies, a stockbroker. “How long do you think those companies would last?”

Young and frustrated

The voice of Japan’s young workers, who are generally underpaid and underpromoted, recently found an outlet in a surprise hit television drama, set in a fictional version of Japan’s largest bank. Much of the country seemed to identify powerfully with the show’s talented hero, Naoki Hanzawa, a loan manager, who kicks back against the bank’s higher-ups and refuses to take the blame, as Japanese corporate culture dictates he ought, for the bosses’ many profit-destroying blunders.Hitachi’s salarymen are similarly cheering the firm’s shift to performance-related pay and promotion. If you are in your late 40s you might be nervous, since the ascent of the corporate ladder now comes with some uncertainty, says one. But younger hires are ecstatic. It won’t even matter as much if you went to the wrong university as long as you work hard, exults another employee. Panasonic, Sony and Toyota are also moving towards more performance-related pay and promotion.

Those who plod their way to the top of Japanese firms tend too often to be conservative and narrow-minded. The way they are rewarded does not provide much incentive to try hard: not only is their pay smaller than that of their peers in other developed economies, it is less tied to their performance (see chart 4). When it comes to aligning the interests of bosses and shareholders, Japan is stuck roughly in the 1970s, says Jesper Koll, an economist and adviser to the government.

There is much more, highly recommended.

It’s tempting to think that we’d be better off if we severely limited the ability of bankers and businessmen to amass large fortunes. But so far no one has figured out how to achieve a dynamic modern economy without rewarding merit. The sad decline of the once dynamic Japanese economy is a case in point.

Of course Japan is far from being the worst off country in the world. But giving its rapid growth in the period leading up to 1991, its quite well educated and highly disciplined population, its relatively long work hours, and its 3.2% unemployment rate, it should not have a per capita GDP (PPP) 30% lower than America, Singapore and Hong Kong, and productivity levels far below those of Germany. Something is wrong.

READER COMMENTS

david condon

Jun 12 2015 at 4:13pm

I would draw a sharp distinction between size of compensation and cause of compensation. I would expect switching to promotion for performance to have the biggest impact, pay for performance to be more modest, and increasing the salary of CEOs to have a negligible impact due to diminishing returns. Your evidence doesn’t relate to your lead statement too well. Hitachi is your main example, but Hitachi’s President only earned $1.4 million US equivalent in 2013, well below US pay.

maynardGkeynes

Jun 12 2015 at 5:01pm

My problem with exec compensation is precisely that it does NOT reward merit. Don’t you wish your salary could be set by the buddies you appointed to their (often overpaid) BOD positions? Or by exec compensation experts who were hired by, guess who? Are many of the CEO’s immensely talented individuals? Yes. Are their salaries determined by a “market” by any meaningful definition of that term? Ha!

Gene Marsh

Jun 12 2015 at 6:06pm

Please correct me if I’m wrong but doesnt each and every post here align perfectly with the desired messaging of the wealthy and the business elite (not counting appeals for the deregulation of hair braiding and legalization of soft drugs which (for the time being) run orthogonal to those interests.)

What bothers me is that this fealty to a single interst group is elided, effaced, concealed, whatever.

Here is another post (my apologies mr. sumner as you are the least rigidly-aligned with the agenda of the us chamber of commerce- proving the rule) meant to explain away inequities that benefit the ultra-wealthy. Its this vigilantly vanished imperative which makes the transparently insincere feels about the disemployment effects of the minimum wage so embarrassing to watch.

Its never “our concern is that business must have cheap labor, the cheaper the better and plenty of it” which motivates your rigid, unchanging opposition to paid sick days, minimum wage increases and any other employee benefits. Never that.

You only object on the absurdly counterintuitive grounds that, in all cases all policies designed to help labor are paradoxically doomed to harm labor.

I’m not implying you haven’t deceived yourselves and are actively malicious. I’m saying that part of being an effective libertarian is wearing a mask

that conceals ideas that are known to be alarming or odious to the average human being.

What I think is happening hear is a libertarian-cautioning variation of John Updike’s quote “fame is a mask which grows into the face”.

Like a hapless watergate-era toupee’d would be lothario who doesn’t realize the obviousness of the artifice, you seem to think you’re making the scene at the Disco of the Down and Out, but your lack of self-awareness scotches any chance of being taken seriously.

Just be yourselves. Be your interest group. You just might meet a nice mexican chick with black-market braids down to smoke some dope and stay the night.

E. Harding

Jun 12 2015 at 7:04pm

“I’m saying that part of being an effective libertarian is wearing a mask

that conceals ideas that are known to be alarming or odious to the average human being.”

-As Sumner points out, the “average human being” can be made to say almost anything if asked the right questions, and is generally quite ignorant.

Warren Buffet supports higher taxes. As Bryan Caplan frequently points out, the relationship between income and support for free-market policies is quite weak. Academia, Hollywood, the media and software are notoriously left-wing.

And ad hominem arguments never work.

Gene Marsh

Jun 12 2015 at 8:25pm

“Warren Buffet supports higher taxes. As Bryan Caplan frequently points out, the relationship between income and support for free-market policies is quite weak.”

It’s what you’d expect of someone whose policy preferences change with the facts. At another time,

in another economy Buffet would think taxes were too high.

I got the feeling from Bryan’s post last post on the minimum wage that no evidence will ever change his mind that the policy is evil. It frankly shocked me. I’d think he’d be glad to see accept a bet on potential employment effects of the doubling of the minimum wage.

At any rate David, I’m asking to be corrected. Give me some to some posts by the hosts that do what Buffet does when he supports having his taxes raised, what Hollywood does when it makes movies like Top Gun or 300. What academia does when it tenures people like Kevin McDonald or protects the free speech rights of conservative student publications.

I’m sure there’s plenty of places where the author’s preferences diverge from those of the global business elite. I just can’t find them.

Henderson and Caplan seem like super nice people.

All my neighbors are talk radio libertarians and we get together all the time. I come here to understand more sophisticated versions of their arguments and have turned many on to this site.

I also appreciate Econlog publishing my comment.

I recognize how impertinent it may appear to others.

NZ

Jun 12 2015 at 8:27pm

WRT to the frustration of young Japanese workers, I see a minimum wage debate analogy here.

Anyway, we hear a lot about big Japanese companies and their cultures, we see footage of people in big highrise office buildings or huge factory floors all doing tai chi together and stuff like that. But what’s the small business climate like in Japan?

I work for a small business (fewer than 25 regular employees) and we have what sounds like a similar kind of employees-and-their-families-centered atmosphere as Hitachi’s, and it’s great. I love it. I would turn down a job offering 120% or 125% of my current salary to stay with my company because all the non-monetary aspects of working there are so fantastic. Is that something that can only happen at the small business scale?

AbsoluteZero

Jun 12 2015 at 10:46pm

Scott,

Regarding Japan, what most people don’t seem to know is that it’s rather inefficient. There are many examples.

Go to any construction site. You’ll see a few old guys in uniform standing around usually hold glow sticks. They’re not really security guards. They basically do nothing. They’re hired as a matter of default. If there’s road work, the area will be roped off. There are usually at least two such people. At one end, one waves you by with the glow stick as you approach. Another will do the same at the other end.

Phone booths. Go to, say, Shinjuku, walk around, and count how many you see. They’re mostly not used. In fact, most people today use them for only two purposes. You go inside to use your own phone so you have some quiet and privacy. The second is people go inside them to smoke. They all work and are kept in mostly decent shape. There are entire departments with teams of people responsible for maintaining them.

Renting an apartment. I won’t go into the details. Suffice it to say it involves several more people than you would expect (assuming you’re from North America, or Hong Kong, or even mainland China). And it’s not uncommon to have to pay up to 6 months of rent just to move in.

Subcontracting. Say a large company A contracts out a part of a project to a small company B. B in turn contracts out to another small company C. This seems normal, until you find out B doesn’t do any of the work. The whole thing is done by C. And C might contract all or part of it out to yet another small company. They even have a word for it, 丸投げ (marunage). A maru is a ball, or the whole thing. Nage is throwing. So, throwing the whole thing to another company.

BTW, the TV drama is titled 半沢直樹 (Hanzawa Naoki), the same as the name of the protagonist. It came out in July of 2013. It was indeed very popular, and not only in Japan. It was popular in pretty much all the regions in Asia where people like Japanese TV drama.

Tom West

Jun 13 2015 at 9:52am

How egalitarianism failed Japan

I find the implication of this headline interesting. It suggests that economic growth, not the happiness of its citizens is the highest good.

Now, I suspect that moves like Hitachi’s do increased over-all happiness (humans love stability, but also opportunity), but as far as the article is concerned, growth and profits are the only metric worth consideration when structuring a society. Happiness just doesn’t factor.

Articles like this reinforce the uneasiness that many have when economists start making policy suggestions that affect society as a whole. Sometimes the recommendations feel a lot like “Increasing economic growth is the purpose of society” rather than “Economic growth is an important factor in human happiness – these measures increase economic growth.”

Scott Sumner

Jun 13 2015 at 12:18pm

David, I think it’s interesting that progressives cite Japan as an example of why we should pay CEOs less. Japanese CEOs have performed incredibly poorly, as almost all knowledgeable observers concede. Now you are quite right that we don’t know that this poor performance is due to the lack of pay incentives, but nonetheless it’s a strange case to cite in favor of egalitarianism.

Maynard, How would you reform corporate governance so that shareholders had more say over executive pay?

Gene, You said:

“Please correct me if I’m wrong but doesn’t each and every post here align perfectly with the desired messaging of the wealthy and the business elite.”

Most of my posts are in favor of the interests of the rich, but all of my posts are in the interests of the poor. In cases where their interests clearly diverge, I favor the poor. For instance, I favor progressive consumption taxes (up to 80% MTRs on the super rich) and low wage subsidies. That policy of redistribution helps the poor and hurts the rich. I can’t think of any policies I favor that help the rich but hurt the poor. If you find any let me know and I’ll change my mind.

You said:

“You only object on the absurdly counterintuitive grounds that, in all cases all policies designed to help labor are paradoxically doomed to harm labor.”

That’s not true. I’ve called for tax cuts for low paid workers, and wage subsidies for low wage workers. As far as “absurdly counterintuitive”, would you agree that all of the recent labor policies in Venezuela were “designed to help labor”? How are those policies working out? Can you explain why they are not working out? Hint, the effects of economic policies are often counterintuitive. Maybe that’s why the liberal NYT endorsed abolishing the minimum wage in 1987.

More broadly, don’t you think it’s kind of strange to accuse me of supporting an interest group (business elite) to which I am not a member? Why would I even want to do that? I tend to find that when commenters don’t have logical objections to my posts, they attack my motives. I’m not saying that’s true in your case, but it’s a pattern I’ve noticed over the years.

Absolutezero, Yes, I’ve also heard of some of those. It would be interesting to know which ones reflect government policies, and which are merely cultural quirks. But also keep in mind that I could construct a similar list for America that would be as long as the Manhattan phone book. It’s amazing that economies work at all.

Tom, I agree, but I also think the burden of proof should be on those who favor policies that reduce output. Those policies might be justified if they raise happiness (say cleaner air) but the burden of proof is on the proponents of those policies.

andy

Jun 13 2015 at 2:15pm

@Gene: I got the feeling from Bryan’s post last post on the minimum wage that no evidence will ever change his mind that the policy is evil

I have read Bryan’s post differently – extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. The problem with minimum-wage supporters is that they have no idea how extraordinary their claims are and are surprised that their extraordinary claims are not accepted when they present mediocre evidence.

As for Japan: I visited it a few years ago and I was surprised about the inefficiencies. People showing you exit routes in a parking place (with clearly marked exit routes). 4 people in a drugstore on Saturday (a drugstore without laboratory); when I asked how many clients comes that day I was told that about 60.

Comments are closed.