The title of this post might seem a bit strange, for several reasons:

1. The tax cut was widely blamed for causing a recession

2. I’m a libertarian that favors low taxes

In a first-best world I’d like to see the Japanese move toward the Singapore tax regime, which has much lower taxes that Japan. However, if the Japanese government insists on current levels of government spending, they really need to raise taxes. Not because they couldn’t keep on the current track for many years—they could. Rather the problem is that if Japan keeps borrowing money and rapidly increasing the ratio of debt to GDP, then they will become more and more susceptible to an economic shock, like higher interest rates. Financial crises always seem far off, until they are suddenly upon you.

The current government of Prime Minister Abe took power at the beginning of 2013, promising to boost economic growth and implement a 2% inflation target. They also promised to reduce the budget deficit, by raising the national sales tax in 2 steps. On April 1, 2014 they took the first step, raising the tax rate from 5% to 8%. The second increase from 8% to 10% was scheduled for later this year, but has been postponed to 2017. It should be moved up if possible.

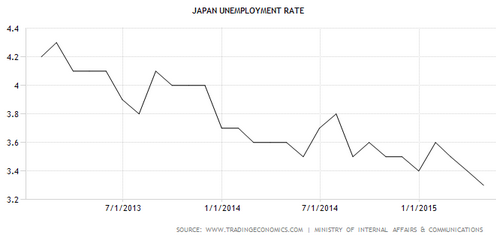

In 2014, the American media reported that the April sales tax increase drove Japan into a recession. As you can see from the unemployment graph, that’s not true:

Unemployment has been falling ever since Abe took office, and is now at fairly low levels, even by Japanese standards. Inflation increased, although the recent oil price collapse reduced it again (perhaps temporarily.) The total number of employed workers has been rising, despite a rapidly falling working age population. Stocks are soaring. In December 2014 the Japanese voters shrugged off the so-called “recession” and gave Abe a huge, overwhelming mandate.

The post-tax increase downturn was falsely labeled a recession for two reasons. First, most American reporters don’t know that Japan’s trend rate of economic growth is roughly zero, and hence positive and negative quarters are equally likely. And second, even with full 100% monetary offset (which occurred in this case) consumers will time purchases to avoid the tax increase. Thus GDP rose sharply in 2014 Q1, and then fell sharply in 2014 Q2. That’s simply a timing issue, and (as we can see from the Japanese unemployment rate) has no implications for the business cycle.

Again, I’d love to see Japan adopt a libertarian policy regime, but they aren’t going to do so. The Abe government is committed to a fairly high level of spending (by East Asian standards, not by European standards). But they are also blessed with one of the greatest central bankers in world history, Haruhiko Kuroda. They should take advantage of this opportunity by implementing the second tax increase as soon as possible. Unfortunately, they seem more interested in undercutting Kuroda:

AN EARLY strength of Abenomics, the plan of Shinzo Abe, the prime minister, to revive Japan’s economy, was the tight bond between Mr Abe and his handpicked central-bank governor, Haruhiko Kuroda. Former chiefs of the Bank of Japan had adopted a defeatist stance towards Japan’s deflationary morass. Mr Kuroda, the prime minister believed, was a champion of his desire to revitalise Japan in large part through unorthodox monetary loosening. In early 2013, soon after Mr Abe took office, the central bank duly launched a radical programme of quantitative easing.

But now the two men appear at loggerheads. The main point of contention is fiscal policy, which to date has been very loose, with a primary budget deficit (that is, excluding interest payments on debt) of 6.6% of GDP. Mr Kuroda (pictured) is making it clear that he does not believe Mr Abe is trying hard enough to bring the deficit down. The government, meanwhile, would prefer him to confine his remarks to the bank’s monetary remit.

A second and related difference is emerging over monetary easing itself. In the quest to rid Japan of deflation, Mr Kuroda promised whatever it took to push inflation up to 2%. The Bank of Japan may not be doing enough to achieve this. Prices are at a standstill. Yet the government appears to be signalling that a fresh bout of bond-buying might be too much of a good thing. Having ordained the inflation target, Mr Abe now appears to be undermining Mr Kuroda’s ability to reach it. . . .

To forestall further easing, some advisers even speak about changing the Bank of Japan’s 2% inflation target to a more modest one, of perhaps 1%.

Given their recent huge election victory, achieved with the new 2% inflation target, a drop to 1% could only be described as an “unforced error.”

If you think that you’ve now got Japan figured out (Abe hawk, Kuroda dove), think again. Just a few paragraphs later The Economist makes this bizarre claim:

Mr Abe has promised detailed plans in the summer for reducing future deficits. Swingeing cuts to social-security spending probably remain politically off-limits. Yet radical measures are needed. They will have to include getting elderly Japanese to pay more for their medical care. A health system that keeps too many people in hospital beds for too long needs to be overhauled. And the retirement age needs to be increased further. The most important test of the relationship between Mr Abe and Mr Kuroda will come if inflation picks up in earnest, at which point the central bank will begin to tighten its monetary policy. Mr Abe may insist on keeping the monetary taps open to safeguard growth. A premature falling out may only make that moment harder still.

As I keep saying, monetary policy failures are not about special interest politics. There is an almost mindboggling lack of understanding of monetary theory at the top levels of government. The entire world economy is resting on the hope that a few sane people like Haruhiko Kuroda can keep their head and keep NGDP chugging along while the rest of the political establishment careens recklessly from one extreme to the other.

READER COMMENTS

Kenneth Duda

Jun 21 2015 at 11:04pm

> The entire world economy is resting on …

> a few sane people like Haruhiko Kuroda …

Of course, if we could institute sensible monetary policy (i.e., prediction-market-guided NGDP level targeting), we would no longer need to rely on individual central bankers.

$0.02

-Ken

Todd Kreider

Jun 22 2015 at 5:10am

1) Unemployment has been falling ever since Abe took office,…

True. It has also steadily fallen each year from 2009 when it peaked at around 5.5%.

3) First, most American reporters don’t know that Japan’s trend rate of economic growth is roughly zero

From what year is this trend being measured? It isn’t zero from 2011 or 2012. Looks closer to 1% than 0%.

Two bad quarters in a row is at least a case for recession. Was there also no recession in 2012 when unemployment was also falling, the stock market was rising and three quarters in a row were mildly negative?

Todd Kreider

Jun 22 2015 at 7:42am

2) if Japan keeps borrowing money and rapidly increasing the ratio of debt to GDP, then they will become more and more susceptible to an economic shock, like higher interest rates. Financial crises always seem far off, until they are suddenly upon you.

In the case of Japan I’d say it is the opposite. There have been many predictions of Japan going into a financial crisis: Adam Posen insisted a crisis was around the corner in 2002. The finance minister insisted in 2010 that Japan faced a financial crisis by 2015. That year, Ken Rogoff thought Japan would be in a financial crisis by 2020. Takeo Hoshi wrote in 2014 that “Japan is defying gravity” and that without significant tax increases Japan will face a crisis by 2023.

2002 to 2023 is quite a range. As far as I know, no economist has successfully explained what debt ratio is not sustainable.

The huge error that is almost unanimously made by Japan experts, watchers like Rogoff and journalists is the assumption that health care costs will naturally keep going up and up, completely ignoring what is happening with medical science including the coming super health pills quite soon. Actually, the first ones may already be out.

The projections out to 2060 of elderly population, workers, etc. are garbage after around 2020 yet are used as if considered “scientific”. They aren’t. They are sciency.”

Michael

Jun 22 2015 at 8:06am

Doesn’t Japan do its borrowing in Yen? If so, I fail to see the problem, or potential for crisis. Given that they remain below the inflation target, the brilliant central banker should be happy to finance a couple years of deficit through seigniorage. Clearly he does not want to, but why? What is nature of the feared crisis?

J.V. Dubois

Jun 22 2015 at 8:35am

I really do not understand this reporting. How can there be these two paragraphs next to each other?

“Having ordained the inflation target, Mr Abe now appears to be undermining Mr Kuroda’s ability to reach it”

AND

” … if inflation picks up in earnest, at which point the central bank will begin to tighten its monetary policy. Mr Abe may insist on keeping the monetary taps open to safeguard growth.”

I don’t know if this mess was created by inept journalists who thought they were doing an honest analysis or if they really captured the madness that is a conduct of monetary policy in Japan.

Abe supposedly does not want another QE but he simultaneously wants to “keep the monetary taps open”. Kuroda desperately wants to increase inflation but at the same time he wants to tighten if “inflation picks up” – which may mean that Kuroda wants inflation exactly where it is now? I do not really know.

However I suspect the former, I think that the journalist themselves just write all these words on the paper without ever understanding that it is nonsense. Otherwise mere existence of such insanity on governmental level would have to be the main story.

I don’t know, is there another area where journalist report evidence contradictory to their analysis, not even blinking? Imagine reading something like this:

“By withdrawing US military personnel from Iraq Obama wants to achieve stronger military presence in the region” or “The recent round of economic sanction are aimed to strengthen the position of Russia as our strategic trade partner”

Is it just economic journalists that do not have any respect for basic logic? I really do not know.

Scott Sumner

Jun 22 2015 at 9:07am

Ken, Good point.

Todd, You asked:

“Two bad quarters in a row is at least a case for recession. Was there also no recession in 2012 when unemployment was also falling, the stock market was rising and three quarters in a row were mildly negative?”

That’s right, the last Japanese recession was in 2008-9, if you look at a graph of the unemployment rate.

Yes, unemployment was falling before Abe took office, but it’s now at a level lower than at any other time in the 21st century, even lower than at the peak of the 2007 boom. But obviously that doesn’t prove Abe’s policies caused that outcome, just that his policies certainly don’t seem an obvious failure.

The growth since 2011 has averaged greater than 0%, as you say, but that’s not how one establishes the trend rate of growth. The trend rate is the RGDP growth rate over a substantial period where the unemployment rate is stable. And since unemployment has been falling since 2011, the recent growth rate has been above trend.

I completely agree with your comments that it’s almost possible to predict financial crises, and I’ve never tried to do so. I make a much weaker claim; the larger the debt burden the greater the risk, that’s all.

I happen to think there is more than a 50-50 chance that Japanese rates will stay low.

Michael, We are not talking about “a couple years of deficits,” but rather many, many decades, perhaps centuries.

JV, I see that sort of “madness” all the time, even in the US. In my view it’s not the journalist, it’s the situation. Consider that just a few years ago Abe officials were demanding a 2% inflation target. Now some want it reduced to 1%. Why? My guess is that (like Westerners) they don’t understand monetary policy.

Todd Kreider

Jun 22 2015 at 9:43am

Scott,

This is the first time I’ve seen a recession defined solely based on unemployment figures.

At first I assumed you were using “trend” in the common long range use but “around zero” didn’t seem correct. I’m also not sure how you define “stable unemployment. For Japan, is a range of 3.5% to 5.5 % stable?

Assuming it is, if one goes back to 1991 and looks at real GDP/capita, Japan went from $28,000 to $31,800 in 2005 dollars according to Penn Tables 7.1 (stops at 2010)

Not a rip roaring 19 years but still 0.7% trend a.k.a. “closer to 1% than 0% growth.”

Now, something tells me you are not going to fully appreciate using real GDP….

By the way, wouldn’t a long term 0% trend just mean Japan has been in one long recession apart from relatively low unemployment?

Mr. Econotarian

Jun 22 2015 at 1:40pm

Japan having a low unemployment is not news.

The problem is that plenty of people are employed in Japan, but overall productivity is low.

Japan’s productivity is still 70% of the US. This is despite having a very modern economy, low crime rate, and high-IQ population. Japan’s economy is ranked 20th freest in the 2015 Index of Economic Freedom. This is in a country that pretty much invented robotic production, and of course has high speed trains 🙂

I think you have to look somewhere else for the real cause of its low-productivity and slow growth. Lack of immigration?

E. Harding

Jun 22 2015 at 3:40pm

Econotarian, I suspect protectionism and failure to liberalize the economy.

Michael Byrnes

Jun 22 2015 at 9:24pm

Todd Kreider wrote:

“This is the first time I’ve seen a recession defined solely based on unemployment figures.”

This gives me an opportunity to mention what is still my favorite Scott Sumner post.

If more people focused on unemployment as the key indicator of recession, we’d probably have fewer recessions.

John Hicks

Jun 23 2015 at 10:40am

[Comment removed pending confirmation of email address. Email the webmaster@econlib.org to request restoring this comment. A valid email address is required to post comments on EconLog and EconTalk.–Econlib Ed.]

Todd Kreider

Jun 23 2015 at 4:30pm

I think Scott makes a good point with respect to unemployment and why I found it hard to believe that when Japan went through the 2008/2009 recession, The New York Times only reported the unemployment rate once in all articles I had read on Japan’s economy at the time. Even an economist focusing on Japan never mentioned Japan’s unemployment rate in his WSJ and Foreign Affairs articles.

Still, I don’t understand using only unemployment

Comments are closed.