Tyler Cowen has a good post on the catastrophic collapse of the Brazilian economy:

And how is Brazilian output doing you may wonder?:

By the end of 2016 Brazil’s economy may be 8% smaller than it was in the first quarter of 2014, when it last saw growth; GDP per person could be down by a fifth since its peak in 2010, which is not as bad as the situation in Greece, but not far off. Two ratings agencies have demoted Brazilian debt to junk status. Joaquim Levy, who was appointed as finance minister last January with a mandate to cut the deficit, quit in December.

One thing I’ve noticed is that commenters attempt to find excuses for the failure of the model that Paul Krugman assured us was just fine, as recently as 2012:

Just to be clear, I think Brazil is going pretty well, and has had good leadership. But why exactly is Brazil an impressive “BRIC” while Argentina is always disparaged? Actually, we know why — but it doesn’t speak well for the state of economics reporting.

Perhaps the most bizarre excuse is that it’s China’s fault. Here’s one of Tyler’s commenters:

Hey, Tyler, you are one of the people touting negative stories about what is going on in China, and I am largely sympathetic to your claims on that front. So why are you picking on the Brazilians so hard, arguably the worst victims of the Chinese deceleration and outright decline in sector directly importing from Brazil?

That’s right, the collapse of a major continental economy on the other side of the world from China, which isn’t even particularly heavily exposed to international trade, was (we are told) caused by Chinese growth slowing from 7.3% to 6.9%, or perhaps to 5% if you believe the China conspiracy theorists. I’m picking on one commenter, but I often read this claim being made.

Now in fairness, Chinese growth in the heavy industry sector has slowed much more sharply than the overall economy, and that has depressed the price of iron and coal. But consider this data:

There are many problems with the “blame China” argument, but I’ll just mention three:

1. Brazil is not particularly exposed to international trade. Australia exports more than Brazil, even though Brazil has nine times the population of Australia, and three times the GDP.

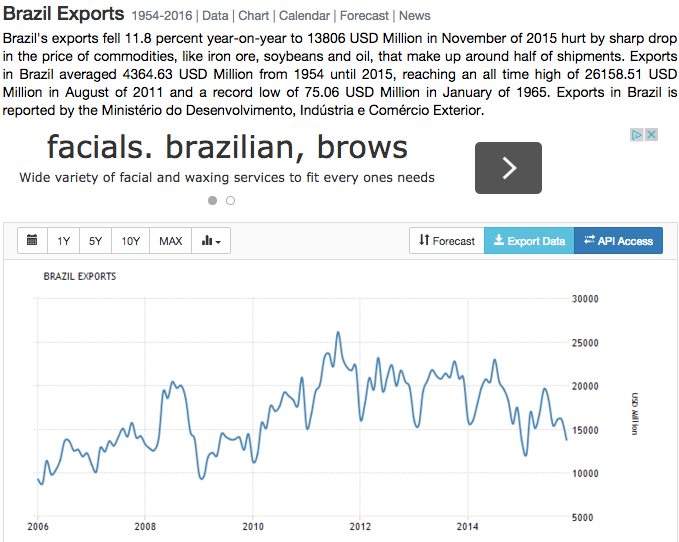

2. Australia exports lots of coal and iron, which are especially hard hit by the slowdown of heavy industry in China. Brazil exports lots of soybeans, oil and iron, only one of which is directly impacted by the drop in Chinese heavy industry. The Chinese continue to rapidly increase their rate of car ownership and their consumption of meat. Yes, those prices have also declined, but for reasons having little to do with China. Furthermore, Brazilian exports are only down 11.8% year over year, and the article suggests that’s mostly due to lower prices. So I see little evidence that the real volume of Brazilian exports has plunged sharply. And yet real GDP is expected to be down by 8%, and even more in per capita terms. All this in a continental-sized economy that (like the US) mostly serves the domestic sector.

3. Maybe you don’t like the comparison to Australia, which is much more advanced than Brazil. Then how about the rest of Latin America:

Moreover, many Latin American economies will continue to face growth divergence in 2016. Again, the Atlantic-facing economies of Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela–the largest members of the Mercosur bloc–will either experience meagre economic growth or remain in recession. On the other side of the continent, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru–which make up the Pacific Alliance–will experience stronger expansions. Nevertheless, growth in the Pacific Alliance economies is expected to remain below potential due to the headwinds caused by still-low global commodities prices, the potential impact a Fed rate tightening could have on financial conditions, as well as domestic political challenges.

Yes, lower commodity prices have definitely slowed growth, especially in economies like Chile and Peru, which are heavily dependent on the export of minerals like copper. But this article says that the consensus forecast calls for growth in the 2% to 3% range in the relatively neoliberal Pacific economies. In contrast, Argentina is expected to have 0.4% growth, whereas Brazil and Venezuela will see outright declines. I don’t want to overstate the policy differences, none of the countries are either neoliberal or socialist models, but there is no question that the Atlantic economies have tilted more in the socialist direction.

Many Keynesian commenters used to complain when I pointed out that Australia avoided recession in 2008-9 by keeping NGDP close to the long-term trend line, through sound monetary policy. They said Australia was simply lucky, due to its commodity exports to China. Well now Australia is getting walloped by much lower commodity prices for its coal and iron exports, and yet the consensus forecast for Australia calls for the same 2% to 3% RGDP growth that is expected in the more free market part of Latin America. What happened to the claim that commodities were so all important to these countries that they could overwhelm the business cycle? Is it still true for Brazil, but not the much more exposed Aussie economy? I don’t get it.

For years, left-leaning economists like Paul Krugman have been telling us that demand-side factors were key, and supply-side economic reforms were overrated. The leader of the British Labour Party praised the socialist government of Venezuela, which makes even Brazil look somewhat sane by comparison. I think we are finally seeing that the left is paying a price for forgetting the lessons of the 1970s. Markets work and statist policies don’t. How did this happen? How did they forget?

I think they overreached. After 2000 the GOP took some increasingly silly positions on a wide range of issues. They became widely viewed as the “stupid party.” Then you had the global economic crisis, which was wrongly (but perhaps understandably) blamed on laissez-faire policies of deregulation. Progressives started thinking, “maybe the right is wrong about almost everything, including the need for neoliberal policies.” Intellectuals moved sharply to the left, especially younger ones with no memory of the failures of socialism. Polls show many younger Americans, especially Democrats, have a positive opinion of socialism. You see serious economists contemplating policies that in the 1990s would have been regarded as loony, like rent controls, or a $15 nationwide minimum wage. And you had serious economists overlooking the horrible consequences of statist big government policies in Brazil, Greece, Argentina, Venezuela, etc.

In 2009 I thought this was another 1933 moment, where the left would greatly benefit from a “crisis of capitalism”. Now I’m not so sure. It looks to me like a failure of both left and right in the US, and the only countries that will do OK are those where the right has kept its head, such as the other English speaking countries, the Nordic countries, and East Asia. I see two key differences from 1933:

1. In 1933, most governments were small by modern standards, so there was room to grow. Now Brazil’s public sector spends 40% of GDP, which is very high for a developing country. And despite all that spending, they are not building modern infrastructure like China, where government spending is far lower, but better targeted to growth.

2. In the mid-20th century, growth was more like a military operation—mobilizing resources to produce things like steel and washing machines. Even the Soviets could do it. But when the global economy shifted toward high tech and services, the need for a flexible market economy became much greater. After the 1970s, growth slowed almost everywhere, but especially in the more rigid, statist economies.

So today the failures of socialism are immediately exposed as soon as their economies are no longer propped up by commodity exports. Brazil is the poster child for this phenomenon, but it’s happening many other places as well.

PS. Mea culpa. I did expect Venezuela and Argentina to do poorly once the commodity boom ended, but did not realize how bad things were in Brazil. The scale of the disaster has caught me off guard. Ditto for Greece. I knew the euro might be a problem for them, but never imagined it would get this bad. So perhaps I’m putting too much weight on socialism. But I am quite confident that Brazil’s depression cannot be explained simply by pointing to lower Chinese demand for commodities—the numbers simply don’t add up.

READER COMMENTS

John Hall

Jan 4 2016 at 9:45am

You might have also mentioned the corruption scandal (and Operation Car Wash).

Brazil still has a legacy of hyperinflation, which makes them less susceptible to some types of bad policies. However, it’s not like Dilma is some new person: she was the hand-picked successor of Lula. She’s just continuing his policies. Strong growth, with support from rising exports to China, may have made some policy mistakes less noticeable.

Also, it’s a Scott Sumner post, where’s the comparison of Brazil NGDP to trend?

marcus nunes

Jan 4 2016 at 10:32am

Got the prediction right: Mr Levy became the “neoliberal scapegoat”!

https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2015/02/26/brazil-not-yet-sinking-but-bogged-down/

marcus nunes

Jan 4 2016 at 10:38am

Brazil´s “doom march” has been going on for some time:

https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2013/05/21/what-a-feat-brazil-managed-in-three-short-years/

marcus nunes

Jan 4 2016 at 10:43am

Brazil vs India:

https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2015/03/21/india-brazil-expansionary-fiscal-austerity-vs-contractionary-fiscal-expansion/

marcus nunes

Jan 4 2016 at 10:48am

Brazil has been “damaged goods” for a long time

https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2012/04/29/why-brazil-doesn%C2%B4t-grow-in-addition-to-rampant-corruption-stifling-bureaucracy-and-other-growth-disincentives/

Jon Murphy

Jan 4 2016 at 11:08am

Correct me if I am wrong, but one of the takeaways I am getting from this post is that socialism is sort of a house of cards: when its growth-dependent areas are growing (in this case, commodities) it can hide many of its structural flaws. But once that protective facade is stripped away (falling commodities), the cracks can more clearly be seen?

Pajser

Jan 4 2016 at 11:58am

I’m looking Google public data, GDP per capita (current US dollars), 2002 – the last year before Lula and 2014, the last year they have in base.

2002: World average: 5500, Brazil: 2700

2014: World average 10700, Brazil: 11400

It seems that Brazil should lose lots more before one can righteously say that Lula’s economy didn’t worked well. Although I am not sure how much of the socialist economy it is.

Jose Romeu Robazzi

Jan 4 2016 at 12:27pm

@Prof. Sumner,

Thanks for this post, it generalizes what everyone should be seeing, but for various reasons, elected to ignore

@Pasjer

You are taking in US dollars a number that is depressed in 2002 (very bad year for the Real) and inflated in 2014 (not a bad year for the Real). BRL fell 44% in 2015 alone…

Blackbeard

Jan 4 2016 at 1:17pm

Yes, socialism doesn’t work and we don’t need Brazil or Venezuela to illustrate that. See the USSR, North Korea, Eastern Europe etc. But why is this a “day of reckoning.” Wasn’t Jeremy Corbyn just chosen as leader of the Labor Party? Isn’t Bernie Sanders doing surprisingly well in the US? Does the average voter even know what socialism is?

The Left is doing just fine. Winning I’d say.

Jon Murphy

Jan 4 2016 at 1:21pm

Jose-

That and Pasjer’s response doesn’t address the point Prof. Sumner is making. The argument wasn’t whether or not Brazil has grown since 2002. The question, rather, is why Brazil and other socialist countries were underperforming (in fact, outright declining) other commodity-based, but more free-market, countries.

Scott Sumner

Jan 4 2016 at 2:41pm

John, I recently did a post about that—not all problems are about NGDP. And this one certainly is not.

Thanks Marcus. You were right.

Jon, Yes.

Pajser, Are those PPP figures? Brazil has huge exchange rate swings.

And see Jose’s comment.

Blackbeard, They are losing everywhere in Latin America, and I don’t think Corbyn is going to lead them to victory in the UK. Ditto for Sanders. Yes, at an intellectual level socialism is increasingly popular in the West. But would you agree that Western intellectuals will have a harder time pointing to “successes” like Venezuela without being laughed at? Sanders now points to Denmark, which is among the most economically free countries in the world according to Heritage. If the Nordics are the new model of socialism, then we are very lucky. I look forward to school choice, as well as privatization of airports, fire fighting, water companies, air traffic control, railroads, postal, etc.

ian

Jan 4 2016 at 2:46pm

Taking GDP growth as a proxy for the economy might not be the best tack. How has the Australian Labor market been doing? The thing that most Australians care about?

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=30165

Steve Phillips

Jan 4 2016 at 3:44pm

[Comment removed. Please consult our comment policies and check your email for explanation.–Econlib Ed.]

Daniel M

Jan 4 2016 at 3:54pm

Nice post.

But Sumner, please, stop adopting the term “neoliberal”. This term was created and is almost exclusively used by people who hate so-called “neoliberalism” (you’re the only exception I know).

Colin Docherty

Jan 4 2016 at 4:39pm

“China commodity boom is over” is much more sophisticated answer than what the average Brazilian would give. If you asked a random person off the street, 9 out of 10 would say “because the politicians stole all the money”. I know because I live in Brazil and done this. They think they’re having an economic crisis because of thieving politicians and corporations, full stop.

Colin Docherty

Jan 4 2016 at 7:11pm

Scott, you may also like to take a browse at the latest austrade export statistics, which just came out today. Some juicy charts for your thesis:

http://www.austrade.gov.au/news/economic-analysis/australias-export-performance-in-2014-15

Aaron J

Jan 4 2016 at 7:16pm

1. People who don’t think China’s growth is not 6.9% are not conspiracy theorists. You are writing on a libertarian blog and yet claim that those who doubt an undemocratic, highly secretive government’s GDP statistics as questionable are conspiracy theorists. Add in the fact that Tyler, who you cite as an authority several paragraphs earlier in another context, is one such person. Not to mention GDP estimates in a country of 1.3 billion aren’t that easy to do in the first place, and we ourselves often have to revise the numbers.

You’ve made reasonable arguments in defense of China’s statistics, but let’s call those who think China is growing at 5% doubters, not conspiracy theorists.

2. Brazil definitely needs serious reform. I think it is worth differentiating between Lula and Dilma. Sure the former benefited from headwinds while the latter has had worse luck, but Lula was more reasonable and a better economic manager than Dilma. Lula promoted anti-poverty, Dilma has been more clientelist.

3. I think you kind of unfairly applying Krugman’s arguments about Western nations post-financial crisis to middle-income countries in the current time period.

ThomasH

Jan 4 2016 at 8:54pm

What does Brazil’s (or Greece’s) woes have to do with “socialism?” Looks like good old-fashioned macro mismanagement — invested in projects that have NPV’s less than zero (the World cup?) — to me.

Investing in projects that have NPV’s less than zero can be just as bad for growth as failing to invest when NPVs are greater than zero.ain

And what do Paul Krugman’s view that AD has been deficient in the US from 2008-15 (and counting) [Yes, he does not lay enough of the blame on the Fed and too much on “austerity” – the failure to invest when NPVs are positive] have to do with Brazil.?

Sam

Jan 4 2016 at 9:12pm

Hopefully Brazil will get a little boost next year from the delayed positive impact of the El Nino.

v

Jan 4 2016 at 10:08pm

[Comment removed for supplying false email address. Email the webmaster@econlib.org to request restoring this comment and your comment privileges. A valid email address is required to post comments on EconLog and EconTalk.–Econlib Ed.]

Daniel Coutinho

Jan 4 2016 at 10:37pm

Many brazilian economists expected that our economy would slow down, mostly due to macro mismanagement and poor institutions: long story short, loads of government intervention. This lead to an huge scheme of corruption (I’m talking about billions of dollars in contracts with the main stat owned petrol company, which are now under scrutiny) and a huge inflation (last years CPI was 10%). And let’s not talk about how messy Brazil ‘s public finance is

However, the most crazy thing about all of this is BNDES, a state investment bank. Yes, it’s as bad as it sounds: they lend R$450 billion (almost 100 billion dollars. Not a typo) with subsidized interest rates (they said that they got the money at the libor rate, while Brazil’s basic interests are never lower than 7%) which led to the formation of big cronies and, gues what? It had no effect on the economy. You guys should write about this kind of bank.

Keep with the great work you do

Jose Romeu Robazzi

Jan 5 2016 at 8:01am

@Aaron J

Lula and Dilma are the same. The seeds of mismanagement in Dilma’s term were sowed during Lula’s term. Those take time to create its effects.

@Daniel Coutinho

BNDES has had a large effect on the economy. A negative one.

Scott Sumner

Jan 5 2016 at 9:40am

Ian, Back in January the Aussie unemployment rate was 6.4%. The most recent reading (November) was 5.8%. How does that change my argument?

Daniel, I like the term, and am proud to be a neoliberal. I think it’s a useful term, and I hope to popularize neoliberal views.

Colin, That’s certainly a part of the problem, but excessive spending on things like pensions is also a part of the problem.

Aaron, They most certainly are conspiracy theorists. I think what you mean to say is that they are justified in thinking there is a conspiracy. I find that claim plausible, as there is real doubt about the data–although I don’t think it’s as far off as some do.

But perhaps I should avoid that term, if the connotation is as you suggest. Good point.

2. I defer to your expertise on point 2. I’d add that the anti-poverty programs actually began in the administration before Lula, and were expanded by him. Those are some of the more intelligent things done by the Brazilian government. The clientism you refer to is the bigger problem.

3. Krugman under-appreciates the extent to which supply side problems hold back southern Europe. In the case of Italy, the south is a disaster area, despite being in the same country as Milan. Governments in the south are extremely corrupt. Actually, the entire southern European economic model is a failure.

Thomas, Excessive state intervention, excessive regulation, excessive state ownership of industry, excessive tax rates, too many government jobs, excessive spending on things like pensions.

You can call that what you like, I call it socialism. BTW, each country has important political parties called “socialist” (including the current party in Brazil) Of course Syriza was originally to the left of Greece’s socialists.

Daniel, Thanks for that information.

ThaomasH

Jan 5 2016 at 10:00am

@ Blackbeard and Scott

If “Socialism” means the economic policies of North Korea, Denmark, Brazil, the UK Labor party (just post Corbin?) and Greece (both before and after Syriza), then it does not mean anything at all and therefore it’s hard to say if “it” is becoming more popular in the West or not.

What’s becoming less popular is “Let’s be nice to owners of existing businesses.”

J.V. Dubois

Jan 5 2016 at 12:20pm

ThoamasH: In the same way you can see laissez-faire (or neoliberal if you will) policies enacted in large varieties of countries ranging from Pinochet’s Chille, to Regan’s USA or post-comunist eastern European countries in 90ties/oughts to countries like modern Denmark/Sweden.

Socialism and Neoliberalism are well defined and useful categories. And both can mean “being nice to owners of existing businesses” in some context, but the end result can be vastly different.

Aaron

Jan 5 2016 at 1:12pm

Scott- I appreciate your point re conspiracy theorists. You are right that it the connotation that I was and am concerned about.

That said, you need not be a conspiracy theorist even in the most literal sense to doubt the Chinese data. If you think the first GDP data release is unlikely to be perfect (and it rarely is) and believe its possible that Chinese officials made optimistic assumptions/estimates that they themselves believed, then the growth figures could be a percentage point or two high without any conspiracy.

I would agree most China doubters do believe that governments officials are actively cooking the books.

Also- I claim no special expertise on the Brazil.

Rob from Australia

Jan 5 2016 at 5:14pm

Scott, might want to also mention that Australia has been lucky in the past two years with Chinese demand for our housing (new and existing) in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane (the three major cities). This has somewhat offset the collapse in the trade weighted index (commodity prices) as over the past month we experienced our largest number of new construction starts since 1994. This is driven by Chinese demand, which if you work with the agents doing these deals with developers is driven by Chinese nationals wanting to secure homes for their children to study at our universities or they are trying to get their money out of China due to ill-gotten gains or suspicion of a 20% depreciation in the currency coming.

Deloitte flies over their own real estate team every second month to China.

Australian finance and legal communities kind of all know they are helping the Chinese get their money out. It is a big business. Our own former National Treasurer tried to rat out his own Chinese neighbour for “illegally” purchasing his US$15m Harbour front home in Sydney.

Pajser

Jan 6 2016 at 2:29am

Scott Sumner, I never heard these 1970’s lessons that leftists shouldn’t forget. As you think it is important, it would be nice if whole post about that find the place in your publishing plans once.

Ricardo

Jan 6 2016 at 9:34am

Scott, I generally like your posts but I think there are some facts about Brazil that you overlooked here.

First, you start making comparisions between Brazil and Australia without acknowleding that Australia isn´t confronting a political crisis of extreme proportions, involving the threat of impeachment of the chief of the government.

Second, there is also a second major crisis with political and economical ramifications arising from the discovery of big corruption rings involving politicians, the CEO´s of big construction and engineering firms (some of them have been arrested) and above all Petrobras, the biggest firm in Brazil. All of this impacts heavily the infrastructure investment in Brazil, since these construction and engineering firms are the same firms involved in the development of many (if not all) big infrastructure projects in the country.

As long as I´m aware, neither Australia neither any other country in Latin America with the possible exception of Venezuela are crossing a political turmoil of comparable extent.

Finally, the party in charge of brazilian executive branch is the Worker´s Party (PT, Partido dos Trabalhadores in portuguese); no “socialism” in it´s name or, by the way, in its practices (actually PT has made some big privatizations). Actually, it´s the main opposition party _ Party of the Brazilian Social Democracy, PSDB _ who displays a hint of socialism in it´s name.

There is no doubt that Brazil is plagued by bureaucracy, a kafkanian tax system and a lot of disfunctional regulations. The same can be said about many other countries (if you hear the Republican Party even the USA enters in the league). But Brazil should take a long stride to be considered a socialist country.

Scott Sumner

Jan 6 2016 at 1:50pm

Rob, OK, but has Australia been lucky for 24 straight years?

Pajser, I have done posts like that, but will try to do more in the future. But think about how the Democrats in the US changed from the 1970s to the 1990s, for instance.

Ricardo. I had forgotten that the official name is the Worker’s Party. Thanks for pointing that out (The press often calls them socialists.) I agree that they are no where near as socialistic as say Chavez was in Venezuela.

I do not believe that the political turmoil surrounding impeachment is causing the depression, indeed I think the reverse is more nearly true. I’d be interested in what you think the transmission mechanism is.

Also keep in mind that corruption is partly endogenous, much more of a problem where the state is heavily involved in the economy. Those sorts of scandals are less likely to occur in private sector oil companies like Chevron (although of course scandals can occur in any company.)

Rob from Australia

Jan 7 2016 at 7:19am

Hi Scott, amusingly we are called the Lucky Country so it could be the case but that is usually just an excuse for weak investigation by Australian economists. At one of the Fed sponsored meetings in Dec 2014 they asked an Australian economist from the Washington Institute (now at Deloitte) what is happening in Australia with the housing price “boom” given the downturn in commodity prices and he just responded “I don’t know”.

I agree with you though, the Reserve Bank of Australia has managed their policy framework well over the past 5 years. I also agree with you that the US Fed has been overly tight when it comes to its own policy, especially after reading your analysis and George Selgin’s. Keep up the great work.

Jose Romeu Robazzi

Jan 9 2016 at 7:52am

@Ricardo, Prof. Sumner

Indeed the ruling party is called “worker’s party”, but make no mistake, its policy menu is very, very socialist. If we let them, we will be closest to Venezuela in a few years. PSDB, the main opposition party, despite having social democracy in its very own name, has a centrist policy menu.

Comments are closed.