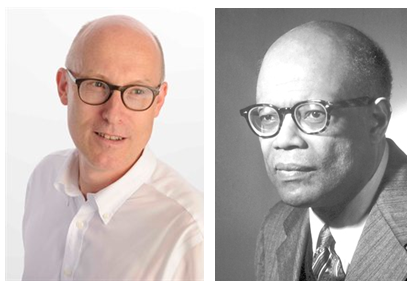

Tim Besley‘s inaugural lecture as the W. Arthur Lewis Professor of Development Economics at LSE can best be summed up as drawing attention to the rise and importance of political economy for understanding questions of economic development. A brief summary is below with the full audio podcast available here.

A major change in mainstream thinking in economics over the past 25 years has been towards improving our understanding of how the policy process (political and bureaucrat) affects policy outcomes. Such changes in economic thinking are partly in response to the need to have a persuasive account of the diverse historical development experiences of various countries and regions. One key debate following this research has been about whether a particular configuration of institutions is needed to promote inclusive economic development. This lecture will take stock of what has been learned and critically appraise the state of knowledge, drawing some implications for how international financial institutions and aid practitioners approach their business.

A few points I found particularly interesting:

Besley begins his talk with a bit of homage to Arthur Lewis, arguing that he won the Nobel Prize because he influenced economists by developing a particular economic model which provided a very powerful narrative for thinking about the process of development. Thus, he argues, if you want to influence the discipline, you have to provide a new and compelling narrative that will guide the subject. One way of interpreting this would be to see the emphasis more on how technical contributions shape the broader narrative of our appreciative theory.

In his own experience coming out of his graduate training as a public economist, Besley recounts having thought the intellectual project he would be engaged in was one of identifying sources of the problems which kept economy’s poor, designing the best possible government interventions, and working with governments to implement these policies. He recalls questioning his faith when Avinash Dixit told him that all the problems in development were essentially political and Anne Krueger at the World Bank pointing out the reality of government intervention in many places showed evidence of corruption and rent seeking.

In sketching the intellectual trajectory and rise of political economy, Besley discusses the importance of the early movements of Virginia School of Buchanan and Tullock and the Chicago School around Peltzman and Stigler, singling out Mancur Olson and James Buchanan as pioneers in political economy. The key turning point being when the central model of benevolent government was questioned as really helpful or obscuring basic understanding of the dynamics of political economy. Besley states clearly that he continues to find the benevolent government model useful, but not in the way he had originally thought. I would be curious to hear how he would further develop this in terms of when and how the model is relevant, particularly regarding questions in economic development.

This all sets the stage for primary focus of his lecture regarding why institutions matter for long run prosperity. He starts with the contributions of Douglass North that institutions create a framework for enforcing property rights and require finding ways for states to credibly commit to not appropriating returns on investment or levy punitive taxation. Besley then points to two trends in the process of economic develop: the openness or contestablity power; and executive constraints over the use of power.

The trends suggest attaining effective executive constraints has proven more difficult than getting “free and fair” elections. I won’t give away all the goodies, but note that I very much agree with the importance of keeping these two characteristics of formal institutions analytically separate, rather than collapsing them in to one measure of democracy. (Mike Munger once made the intuition behind this point salient to me.)

READER COMMENTS

Roger McKinney

Feb 13 2016 at 2:10pm

Very interesting! I especially liked the Mike Munger video. But I think Munger is unaware of the cultural issues that prevent people from taking control of the water pump.

Helmut Schoeck wrote about it in his book “Envy: A Theory of Social Behavior.” He writes a lot about failure in development. Envy is strong in third world cultures. No one would take ownership of the water pump because they feared the envy of other villagers. And the village as a whole would not take ownership of it because their envy caused them to assume that one of their neighbors would get more of the water than them. In cultures like that, people will trust only the nobility or the government to own anything and ensure that the resources are equally distributed.

Daniel Klein

Feb 13 2016 at 3:31pm

Thanks for this nice post.

I just wanted to alert people to the ideological profile of W. Arthur Lewis, here.

Emily Skarbek

Feb 13 2016 at 4:19pm

Thanks, Dan for the link on the ideological profile of Arthur Lewis. I am intrigued by this and plan to do a subsequent post on Lewis. The Fabian influence is perhaps not surprising, but is particularly interesting in the context of the debate on planning and development. Any additional or interesting source material is welcome!

Nathan W

Feb 14 2016 at 11:27am

“One key debate following this research has been about whether a particular configuration of institutions is needed to promote inclusive economic development.”

Probably a lot of the biggest mistakes around have been made by assuming that the set of institutions associated with success in one area are therefore the institutions which are needed for success elsewhere.

In the act of trying to impose these institutions, we necessarily end up at a solution which was never the result of any grassroots effort which is broadly understood or even supported by much of the population.

Ten years ago, this was profound knowledge. Now it seems rather obvious, no?

No institution which abstains from coercion, or policies associated with such an institution, can thrive without some bedrock of support among the public.

For example, in the west it is common to suggest that private property rights are the first institution that needs to come into place.

I have no reason to question orthodoxy about why private property has many economic benefits. But I argue that there are many places where this comes very far down the list. And moreover, private property is highly inconsistent with many existing traditional property systems. When the goal is nothing short of eradicating tradition as the first step, you cannot expect to get very far.

Nathan W

Feb 14 2016 at 11:30am

Dan – while it can be interesting to see such broader profiles, it troubles me that people are unable to evaluate a given piece of writing on its own merit, and are willing to disregard or support it for the fact that the author otherwise has some ideological leaning.

Think for yourself.

But thanks for the link.

Comments are closed.