Back on March 11, 2011, Japan was hit by the worst national disaster to strike a developed country in modern times. Last week, Japan was hit by a human made disaster with a comparable effect on the economy (albeit obviously not in terms of human life). I don’t expect many people will agree, but consider the following news report from March 2011:

The rash of buying of Japanese stocks came after the country’s benchmark Nikkei 225 index, the equivalent to the Dow Jones industrial average, fell 16 percent over two days in panic-driven selling, reaching its lowest level since the 2008 financial crisis. The index bounced back nearly as quickly, jumping 5.6 percent on March 16 and 4.3 percent on March 22. The index is now down 7.8 percent since the earthquake.

Japan’s stocks fell a bit over 6% on the first trading day after the earthquake. As the severity of the quake became clearer, stocks plunged as much as 16%. Then, when it became clear the worst case of nuclear disaster would not occur, stocks recovered so that by March 22 they were only down around 7.8%. (AFAIK they leveled off around there, someone correct me if I’m wrong.)

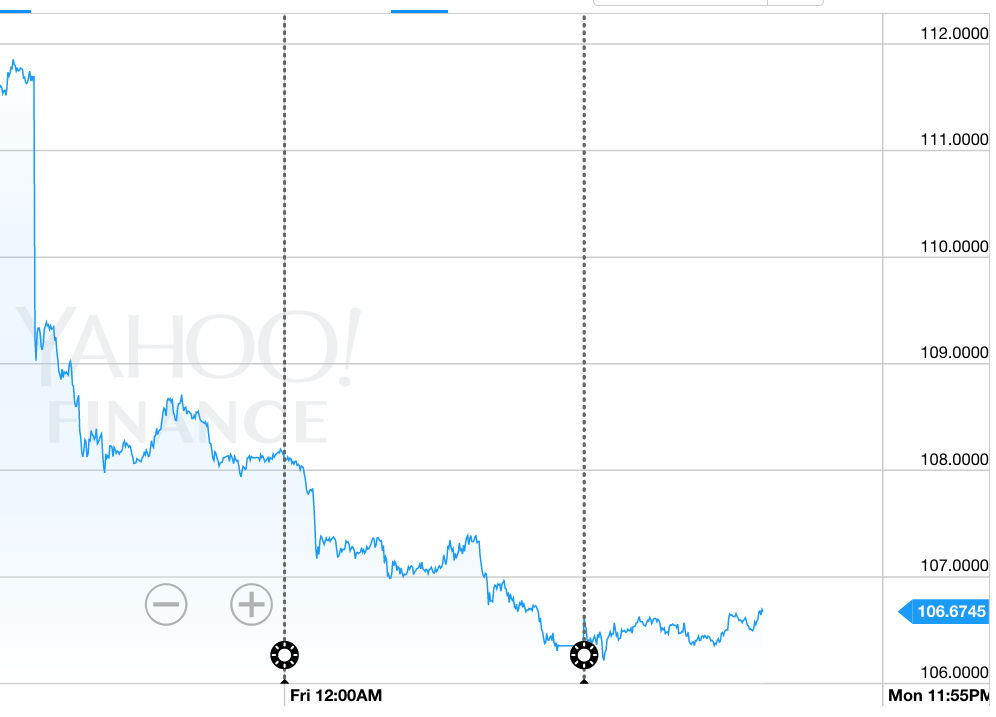

During recent years, major Japanese stock indices have been closely correlated with the forex value of the yen. Late last week, Japan was hit by a yen earthquake, a sharp appreciation in the yen:

The stock market showed a similar pattern, except that the Japanese stock market was closed on Friday, and so the fall that would have taken place on Friday showed up as a much lower opening today. The fall in stock prices since early Thursday is comparable to the fall in stock prices in the weeks after the earthquake:

(Yahoo.com Finance was the source of both graphs)

Even worse, the yen appreciated strongly right after the March 2011 earthquake, so even in that case a good part of the fall in stock prices may have been due to the stronger yen, not the direct effects of the quake. Indeed an emergency meeting of the G-7 was necessary to try to talk down the yen. Notice that the G-7 has no sympathy for the Japanese suffering from 2 decades of deflation—it took a catastrophic earthquake for them to have enough empathy to allow a weaker yen.

The next question is what caused the stronger yen late last week. It’s pretty clear that the initial surge in the yen was due to the Bank of Japan’s unexpected decision not to cut the interest rate on reserves to an even more negative level. I don’t know what caused the further appreciation the next day, but suspect it was related to hawkish statements from government officials, or at least a lack of reassuring statements on the need for more monetary stimulus. If any of my Japanese readers have any information, I would greatly appreciate hearing it.

To summarize, a strong yen that was at least partly triggered by bad monetary policy, can be just as destructive as the worst natural disaster to hit a developed country in modern times. And it’s all so unnecessary.

PS. On the other hand, if you rely on the financial press, you might assume the decision not to cut IOR further into negative territory was good news for Japan.

READER COMMENTS

Jacob A Geller

May 2 2016 at 11:35am

Scott, love the post and love the graphs, but an attribution is always nice too. ?

HL

May 2 2016 at 11:54am

It seems that we already have a smoking gun behind this story. Bennett, Hatch, & Carper. Signed into law just a day before the Shanghai meeting in February.

https://piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/new-us-currency-policy

A bit depressing.

marcus nunes

May 2 2016 at 12:44pm

Scott, they just don´t “get it”!

“The recent jump in the yen is clearly a one-sided speculative move that is extremely concerning and Japan is ready to take action if needed, Japanese Finance Minister Taro Aso said on Saturday.”

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-05-01/aso-says-japan-will-take-action-with-currency-if-needed-nikkei

August Hurtel

May 2 2016 at 1:42pm

Bad news for their stock market. But the Japanese people, who have held on to a preference to cash beyond anything known in America or Europe, have a nice little bump in the value of what they’ve got stashed in the mattress.

Bad news for debt laden companies as well, but sometimes you have to let the bad actors suffer for their sins. Tends to get you back on the right page faster than bailing them out all the time.

Scott Sumner

May 2 2016 at 3:46pm

Sorry Jacob, I added an attribution.

HL, More than a bit depressing.

Marcus, Yes pure “speculation”, there clearly wasn’t any policy news late last week. No “fundamentals.” You wonder if they actually believe what they write.

August, No one was recommending that Japanese borrowers be “bailed out”. I think you missed the point.

August Hurtel

May 2 2016 at 4:46pm

No, I don’t think you are recommending a bailout.

I do think you imagine it would be better if the value of the yen was lower rather than higher. Or, to put it in different terms, the currency provided advantages to the borrower rather than the saver.

Dean

May 2 2016 at 10:27pm

For the record, the earthquake/tsunami was on March 11, not March 7.

HL

May 3 2016 at 2:22am

I think it is a real factor for Japan because they haven’t wrapped up the TPP thing with the US government, which is important for regulatory harmonization and service sector reform. Besides, they have a binding defense treaty with the US, and the current geopolitical situation requires that they play nice with the US electorate….nevertheless, the entire thing is idiotic.

We have a consolation prize today, however. Go Australia! Just one month of inflation undershooting vs. market consensus and boom!

http://www.smh.com.au/business/federal-budget/reserve-bank-of-australia-cuts-cash-rate-to-fight-deflation-20160502-gokm8a.html

Todd Kreider

May 3 2016 at 5:53am

“Then, when it became clear the worst case of nuclear disaster would not occur, stocks recovered so …”

What happened was the worst case scenario. How could Fukushima have been worse?

August Hurtel

May 3 2016 at 9:48am

[Comment removed. Please consult our comment policies and check your email for explanation.–Econlib Ed.]

Scott Sumner

May 3 2016 at 10:03am

August, You said:

“I do think you imagine it would be better if the value of the yen was lower rather than higher.”

I favor targeting NGDP, and letting the market determine the value of the yen.

Now it’s true that my preferred policy, at this moment, would lead to a lower value of the yen, and higher prices for refrigerators in Japan. Bit I don’t think its meaningful to say I favor a lower yen or that I favor higher prices of refrigerators, those are simply-side effects of a stable monetary rule, at this moment. At other moments the side effect would be a stronger yen.

Dean, That’s what I originally thought, before I looked it up (wrong source). Thanks, I changed it.

HL, Yes, good news out of Australia

Todd, I don’t recall the details, but I vividly recall the markets recovering when the worst fears were not realized. Maybe an expert can chime in.

Note that it doesn’t really matter for my argument whether you take the one day reaction in stock prices, or the one month reaction.

Todd Kreider

May 3 2016 at 4:35pm

Scott, I think you are correct about markets improving once the “worst fears were not realized.” I was pointing out that the worst fears were always a fiction based on the reactor type. Nuclear reactors don’t explode, they can’t release dangerous levels of radiation to Tokyo 150 miles away, etc. Physical impossibilities.

It is interesting to note how much sway the fear mongering hype machine of the Western media (especially CNN and the NY Times which Japanese elites pay some attention to) could shake Japanese markets for a dew days.

ChrisA

May 4 2016 at 12:41am

It does seem that the US is basically pressurizing the Japanese not to reduce IOR even more negatively. So the blame for this is US politicians again. It seems like the US is determined to cause another world depression – I wonder what it is about the US political system that has this tendency? Generally speaking the diversified nature of the US political system seems to prevent the worst political excesses, but the virus of “protectionism” seems to be ineradicable by internal antibodies.

August Hurtel

May 4 2016 at 12:32pm

Scott,

I would prefer no target. Your target may be better than what the central bank does now, but then you still have central bankers, a target, and the psychological inertia we have seen with them (and politicians) over and over again. They over or under shoot, over or under compensate, and in times of stress suddenly decide to do things that they never thought they would do.

Mikio

May 5 2016 at 12:11pm

Hi Scott, with regards to the yen/Nikkei, I think what happened is the following:

A few days before the BOJ meeting, Bloomberg reported “sources” saying that the BOJ was considering to cut rates and add a ECB-like lending program with negative rates.

The yen tumbled and the Nikkei rallied on the story, i.e. on speculation that the BOJ would act decisively.

Then the BOJ did nothing and it all came to nothing.

My take is that the BOJ might have acted if it wasn’t for the leak. They decided not to act for internal political purposes (avoid leaks, not appear to chasing markets, etc.), and as a matter of principle. Kuroda wants to stay in the lead.

I believe this is the unwanted “speculation” Aso was referring to.

Meanwhile, since Feb., Abe has appointed two reflationists to the BOJ board, to replace two outgoing financial stability-types. One was approved by parliament. The other will be approved soon (god willing, since LDP has majority). There will be a 7-2 reflationist majority some July, for a 5-4 at present.

This is a politically sensitive time for the BOJ. The big banks hate negative IOR because it takes away a free subsidy. Kuroda has been summoned to parliament to explain the policy several times, with unusual frequency.

Meanwhile, there is a bit of politics going on.

Comments are closed.