The AT&T and Time-Warner merger is attracting considerable attention. The idea of “convergence” between telcos and content providers has been around for quite a while. Still, the idea of “convergence” needs to be tested via the market process. Integrating production and distribution was not necessarily a no-brainer, in the world of atoms. Is the world of bits bound to be different?

Robert Colville, editor of CapX, thinks it is. Colville is the author of “The Great Acceleration“, a book I haven’t read (yet). He wrote an interesting article, expressing a sort of concern with market consolidation:

In industry after industry, the market is narrowing down to three or four big incumbents, in a wave of mergers and buyouts. And when these giants confront each other, the earth quakes – or at least Marmite disappears from the shelves.

Size isn’t by itself a bad thing. It’s economies of scale that have enabled Tesco and Wal-Mart to feed us extraordinarily cheaply – or IKEA to cut the inflation-adjusted price of its signature Poang chair from $300 to $129 between 1990 and today.

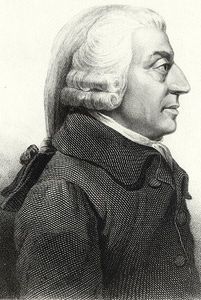

But the problem is that there’s another reason firms become larger – to increase their leverage over their customers. As Adam Smith said, “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.”

There are a number of Smith’s quotes that are misused, but this one beats them all. What follows, in <a href="The Wealth of Nations“>The Wealth of Nations, would put it in a rather different light:

It is impossible indeed to prevent such meetings, by any law which either could be executed, or would be consistent with liberty and justice. But though the law cannot hinder people of the same trade from sometimes assembling together, it ought to do nothing to facilitate such assemblies; much less to render them necessary. A regulation which obliges all those of the same trade in a particular town to enter their names and places of abode in a public register, facilitates such assemblies. . . . A regulation which enables those of the same trade to tax themselves in order to provide for their poor, their sick, their widows, and orphans, by giving them a common interest to manage, renders such assemblies necessary. An incorporation not only renders them necessary, but makes the act of the majority binding upon the whole.

Careful observer of human nature that he was, Smith pointed out that people prefer “protection” for themselves to the open sea of competition whenever possible. And yet he seemed to maintain that, if collusion was a natural tendency, there was little point in attempting to prohibit meetings that were nonetheless bound to happen. On the other hand, the government ought not to make them more profitable, so to say, by regulation and laws making monopolisation easier, if not inevitable.

Getting back to Colville’s article…Is there an evident and uncontested tendency toward bigger businesses in the world we live in? Sociologist Richard Bachmann thinks so and maintains the next US President should pursue a muscular antitrust policy. Mergers within big companies are certainly particularly visible. But we can observe different trends too. For example, some purported Internet “giants” are actually “platforms”, which create markets for smaller suppliers or self-employed people. On top of that, in things like pharmaceuticals and biotech, my impression is that very often innovation happens in smaller firms, which sometimes end up being bought by bigger ones: which appear to be good places to scale innovation up, but not necessarily to generate it.

As a matter of fact, when it comes to integrating production and distribution–the examples of “good bignesses”–Colville cites follow different business models: IKEA sells its furniture through its shop and the web, Tesco and WalMart focus on logistics and marketing of other companies’ products. One of the companies that could be “squeezed” by the AT&T and Time-Warner merger, Netflix, is apparently not very worried.

What keeps markets fertile and sparkling is this “biodiversity” of business models. Sure it needs free entry to be preserved. But whether we should be worried by size qua size, is still an open question.

READER COMMENTS

Harold Cockerill

Oct 29 2016 at 10:04am

More antitrust enforcement could get twisted to actually protect the big guys (lot of money spent on K street for that). Large businesses have an advantage in dealing with an administrative regime that works to hold back start ups. Big businesses in general are not agile which should make them vulnerable to competition from smaller companies but with the growth of the administrative state we’ve seen a decrease in new business formation. Big business doesn’t want that to change.

Too many people want protection both in business and in their personal lives. Government can give short term security but that comes with the loss of long term opportunity. The free market is not so good at short term security but nothing is better for long term opportunity. More government interference in the economy ensures the loss of opportunity and in the absence of a successful movement to make government smaller that’s what the future holds for America.

David R. Henderson

Oct 29 2016 at 11:45am

Good post, Alberto.

Also, in the Industrial Organization literature, there is good reasoning that vertical integration does not typically increase monopoly power, but, on the contrary, can reduce the distortion from successive monopoly.

Comments are closed.