Because tax reform is currently in the news, I thought it would be useful to describe what economists know, and don’t know, about taxes. I’ll start with what we know:

1. Legal tax incidence doesn’t matter. If a tax is imposed on a market, it makes no difference whether the buyers or sellers are legally obligated to pay the tax. Thus the payroll tax is legally split 50-50 between the employers and the employees, but the take home pay of workers would be exactly the same if the tax were paid 100% by employers, or 100% by employees. Ditto for a gas tax. If the original price of gasoline is $1, then a 25-cent gas tax might cause the price to rise to $1.24. If the gas station paid the tax, they’d just boost the price to $1.24. If the consumer had to pay the tax, the gas station would charge $0.99, and then add the 25-cent tax on at the pump (as sales taxes are collected.) This is one issue on which all economists agree, at least on the long run. (Due to sticky wages and prices, the short run outcome may be different.) If you find an economist that does not agree, I’ll reply with the “no true Scotsman” argument.

2. The true economic burden of a tax depends on the elasticity of supply and demand. In most industries, supply curves are very elastic, especially in the long run. Thus most of the burden of sales taxes probably falls on the consumer. If we take the 25-cent gas tax above, it would lead to slightly less driving. This would slightly depress world oil prices. This would slightly depress wholesale gasoline prices. In my example above, I assume the wholesale price of gasoline fell by 1 cent. If so, the 96% of the gas tax would be borne by consumers, and 4% by suppliers (probably oil producers, not gas retailers). This is also an issue on which economists agree.

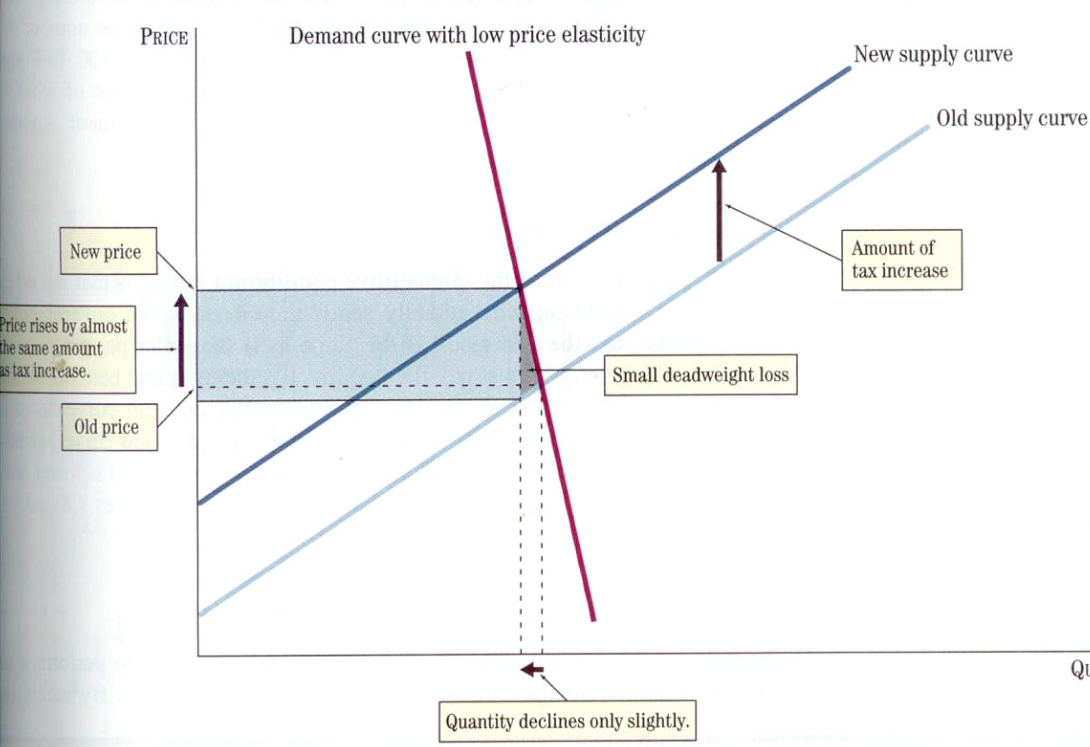

Here’s an excellent graph from John Taylor’s textbook:

3. A more difficult question arises when we look at various types of income taxes. In that case, the long run elasticities are difficult to estimate. Economists do not have a good sense of how much of corporate taxes (or even top bracket personal income taxes) are borne by the rich, and how much are passed on to the general public via higher prices and/or lower wages. We also don’t know much about the Laffer Curve. No one really knows the maximum amount of revenue, per capita, that a developed country can raise via taxes.

4. We do know that subsidies are negative taxes, with effects that are the exact mirror image of taxes. Taxes raise revenue but reduce quantity of what’s taxed, whereas subsidies cost revenue but increase the quantity of what is being subsidized. Again, it makes no difference whether a subsidy is paid to the provider or the consumer.

5. We also know that an equal tax and subsidy exactly offset one another. Thus if gas stations must pay a 25-cent gas tax, but also receive a 25-cent subsidy for each gallon sold, it’s as if nothing happened. No effect at all. If we combine this result with point one above, we know for certain that a 25 cent gas tax on producers combined with a 25-cent subsidy to gas consumers has absolutely no effect on anyone. This is not controversial. However, the price at the gas pump would rise to $1.25 in the second case. After consumers got their 25-cent rebate from the government, they would still be paying $1.00 per gallon. So it would look different.

6. When we move to the realm of international trade, economists see exports as the way of paying for imports (money is just a veil, trade is actually all about barter.) Thus economists believe that a 25% tax on all imports, combined with an equal subsidy to all exports, would have zero effect, for reasons identical to the gas example above. But there is one complication. The exchange rate would rise by 25%, so that the net price paid by importers, and received by exporters, would not change at all.

7. In contrast, if there were only a tax on imports, or only a subsidy to exports, then trade would be distorted. The exchange rate would rise by less than 25%. Importantly, both sides of the trade equation are impacted by tariffs and subsidies, as exports are the way we pay for imports. If we import less, then we export less, at least in the long run. Thus a 25% tariff would appreciate the dollar by less that 25%, and both imports and exports would decline. Protectionism would hurt West Virginia coal, Iowa farmers and Seattle jet makers. And an export subsidy (like Ex/IM Bank) boosts both exports and imports, hurting firms like US Steel, which compete with imports.

Bob Murphy asked me to address three questions:

I think you might also clarify–are you saying the following? (Because it’s very counterintuitive.)

1) An import tax by itself will reduce the trade deficit.

2) An export subsidy by itself will reduce the trade deficit.

3) An import tax coupled with an export subsidy will not affect the trade deficit.

So far I’ve been ignoring trade deficits. When we run a trade deficit, it means we import stuff now in exchange for exporting stuff later. If it seems like we’ll never have to pay for the imports (as trade deficits seem to run on year after year) it’s because the accounting is flawed. To some extent we are paying for imports by earning big profits on overseas investments. That’s the whole “dark matter” debate, which is worth a blog post on its own. Or we might give them some of our property. But the key point is that we must give other countries something of real value (not just paper) for all the cars they send us, unless the other countries are essentially giving us Lexuses and BMWs as gifts.

Tariffs and subsidies don’t have major first order effects on the deficit. Tariffs reduce both imports and exports, and subsidies raise both imports and exports. To the extent they matter at all, it is due to the impact on national saving and investment. Thus tariffs might boost national saving, which would reduce the trade deficit, while subsidies might reduce national saving, which would increase the trade deficit. I say, “might” because there are many factors to take into account, including Ricardian equivalence. Most economists believe that Reagan’s expansionary fiscal policy boosted the US trade deficit. If so, then you’d expect Trump’s likely fiscal policies to do the same. But of course it also depends on what’s happening in the rest of the world, not just the US. To answer Bob’s three questions: yes (a little bit), no, yes.

8. Let me end up on a point where I’m not well informed. Although in theory the proposed border adjustment tax/subsidy should be completely neutral to trade, there are some real world complexities that I don’t fully understand. Suppose part of our goods imports are paid for by UK tourists at Disney World. That service export probably won’t be subsidized. Also suppose part of our goods imports are paid via high overseas profits earned by US multinationals. Is that going to be subsidized? What about sales of LA homes to Chinese buyers? In other words, if the actual plan differs from the textbook assumptions of 100% tax and subsidy, do we still get a 25% appreciation in the dollar? And if we do, is it possible that it occurs not through changes in the nominal exchange rate, but rather the real exchange rate. Thus because of countries like Hong Kong that stubbornly peg their currency to the dollar (nominally), might the dollar only appreciate by 12.5% in nominal terms? In that case, the real adjustment would have to occur via a combination of higher than normal inflation in the US, and deflation in places like Hong Kong, or indeed much of the world. Central banks play a key role here.

Even with all that uncertainty, it’s important to know that economists do understand an awful a lot about taxes. I see many commenters who seem unaware of even points 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, which are all extremely well understood.

PS. If you think that a subsidy of 20% on sales of LA homes to Chinese buyers would be more controversial than the subsidy on goods exports, you are probably right. Which shows just how irrational we are when it comes to trade. We claim to love it when American blue collar workers build jets and bulldozers and sell them to the Chinese, but freak out when America blue collar workers build high rise condos in LA and sell them to Chinese buyers.

READER COMMENTS

Jim Glass

Feb 15 2017 at 5:37pm

You lost me for a little bit part way through your first paragraph. Have I recovered correctly?

Legal tax incidence doesn’t matter [etc.] … The true economic burden of a tax depends on the elasticity of supply and demand….

Agree 100%. Classic examples: Put a tax on cigarettes, it doesn’t matter who legally owes it, smokers are addicted so demand is very inelastic, the price of cigarettes will go up by almost the entire amount of the tax and smokers (consumers) will pay it. (See the price of smokes in NYC compared to just over the border in any direction.) Put a tax on butter, untaxed margarine is a very close substitute, the price of butter has to stay near margarine’s for it to survive in the market, so the price of butter will stay near unchanged and butter producers will eat most of the tax.

In one case the market price goes up on consumers, in the other it doesn’t. That shows who’s really paying the tax. So you confused me with this:

If the original price of gasoline is $1, then a 25-cent gas tax might cause the price to rise to $1.24. If the gas station paid the tax, they’d just boost the price to $1.24.”

If they boost the price to $1.24 then the consumers are paying 24 cents, almost all the tax, so it can’t be being paid by the gas stations.

I reconcile this by assuming you are assuming the price goes up 24 cents (with the economic cost landing on consumers) and the “if the gas station had to pay …” relates to the legal obligation. In which case I guess the word “pay” rather than “remit” confused me. The gas station legally remits the tax that the consumers economically pay.

I hope all this is just my incipient Alzheimer’s slowing me down. Or am I missing something?

Thaomas

Feb 15 2017 at 5:50pm

Nice exposition. I’d like to suggest other topics:

Business income taxes sectoral effects (since they are very uneven)

progressive personal income v progressive consumption taxes

wage taxes v other ways of collecting revenue for SS-Medicare

tax deductions v partial tax credits

Pigou taxes, especially a carbon tax.

mbka

Feb 15 2017 at 9:15pm

Scott,

kudos, posts like these should be mandatory reading for the general public. I’m actually bookmarking this.

As to your 8., the relationship between trade, trade deficits, service exports, and profits from foreign investments, would warrant an entire post which I would love to read from you. I’d be particularly interested in a scale comparison of these factors. What are the relative sizes of service im/exports and foreign generated profits, vs goods im/exports and the trade deficit? For some major economic powers, e.g. US, China, Germany.

Scott Sumner

Feb 15 2017 at 9:39pm

Jim, Yes, I meant if the gas stations had to legally pay the 25 cents to the government.

Thaomas, Good suggestions.

mbka, Thanks, but I’m not sure I know enough to do a post on point #8.

BC

Feb 16 2017 at 5:32am

Legal incidence may not matter economically, but it may matter from a public choice perspective. We seem to end up with higher taxes when the legal incidence is placed on employers instead of employees, firms instead of consumers, imports instead of exports, etc. Shifting legal incidence seems to be a way to fool voters to accept higher taxes (and also mandates, which seem to be economically equivalent to taxes) than voters’ actual preferences.

Zeke5123

Feb 16 2017 at 8:13am

Scott,

Excellent post. I was screaming in my head — what about services! — and then you cover it. That does seem to be the elephant in the border tax room. We pay for most of our imports with services — either in the US or abroad. Failure to account for those likely does make the border adjustment bad for trade.

The other point I want to raise is transaction / search costs and timing. You make the point that a tax and a rebate have an offsetting effect, ceteris paribus. It is highly likely the case that things are not ceteris paribus. First, because of penalties and prospect theory, there is likely a larger desire to ensure taxes are properly collected compared to all subsidies claimed. Thus, even if legally the taxes and subsidies offset, the cost of determine the appropriate subsidy may not justify claiming the benefit.

Second, government tends to collect taxes today, rebate tomorrow. Thus, from a PV perspective the tax tends to be higher vis-a-vis the subsidy.

Finally, as a tax professional I can tell you compliance and planning cost a lot of money. Thus, there should be significant deadweight even if tax is equally offset by subsidy.

AlanG

Feb 16 2017 at 11:41am

What a delightful post with lots of stuff to ponder especially for the non-economist. I have some questions.

3. What about highly compensated Wall Street types. Are their salaries really passed on to consumers? Perhaps a bank CEO’s compensation might be but even that’s hard to see since most bank services are either free or have a very low overhead (and one can always shop around). More to the point, what about hedge fund managers? I’ve a big bias against them in that I don’t see that they really serve much of a purpose other than enriching themselves. How is the consumer impacted.

4. Tax preferences (the term I like) can have interesting impacts. Right now there are credits for solar panel installation and in some cases this can be done for free under rental agreements. Electricity bills can go down to zero or close to it freeing up more money for spending. Now I know alchemy doesn’t work in real life but how is this extra money accounted for.

Scott Sumner

Feb 16 2017 at 4:42pm

BC and Zeke, Good points.

Zeke, On your final point, the border tax proposal is supposed to make the corporate tax system simpler. I’m not a fan of the idea, but in fairness people that know much more than me do think it’s a more efficient system.

But yes, compliance costs are a massive issue, not addressed enough in the debate.

Alan, It’s very hard to know how much of an income tax on hedge funds owners gets passed on to consumers. I suspect that you are right in assuming that it’s mostly absorbed by the hedge funds. (They also benefit from a tax break that seems unfair to me, based on what I’ve read.)

John R. Dundon II, EA

Feb 17 2017 at 1:09pm

Hi Scott! Thank you for this post. As an Enrolled Agent and tax practitioner who signs many hundreds of US business tax returns every year and many hundred more personal income tax returns, might you care to comment on how the woefully understated US ‘tax gap’ might impact some of your thought processes here?

What I see down in the trenches is a LOT of US$ (Benjamins) being stuffed in mattresses all over the planet as a direct manifestation of the US Federal Reserve inflation biased policies.

Getting US Taxpayers to declare those benjamins as taxable gross receipts and actually pay income taxes is a tough business to be in as there are thousands of unlicensed tax practitioners who have no problem filing the most fraudulent of income tax forms without recompense. IRS enforcement budgets are at all time lows, more and more tax payers and tax practitioners alike are cutting corners and shirking rules spelled out in US Treasury Circular 230 causing IMHO the US ‘tax gap’ to be profoundly understated.

With that editorial as back drop, how might the small business owner’s lack of tax compliance combined with the IRS’ decreased enforcement impact some of your thinking? If government can’t collect and small business owners aren’t ‘willing’ to pay the US ‘Tax Gap’ is destined to simply keep ballooning.

Rob Frances

Feb 18 2017 at 10:54pm

“…whereas subsidies cost revenue but increase the quantity of what is being subsidized.”

I don’t think this is a true statement. The government gives billions of dollars of tax subsidies to landlords (interest write-offs and phony depreciation deductions) and we don’t get more apartments because of the subsidies; we only get higher asset prices (land and buildings) and higher rents as landlords compete with each other to invest in rental property to capture the tax deductions and tax-free cash flow.

Similarly, I worked on a number of projects to claim R&D credits (tax subsidies) years after the expenses were incurred that the owners of the business didn’t even know about. They didn’t lower their prices or increase output after finding about this “free money,” so the subsides didn’t increase output.

Statements like “taxes decrease the quantity produced” or “subsides increase quality produced” seem naive, at best. It seems to imply a mindset of ‘Prices = Costs, plus Profit,” although I’ve never seen any company price goods and services this way. It’s always, “what’s the most I can charge potential customers based on what similar goods and services are being priced?”

Dzhaughn

Feb 19 2017 at 4:44pm

Isn’t it better to say “zero net effect on total trade in the long term?” Certainly the mix of imports and exports would change. The timing of compensating barter transactions would change, too.

There is a bonus for those who holding money abroad at the time of the introduction of the tariff/subsidy, I think. I sell $1M of cars to you today, expecting to buy $1M of movies. But thanks to the 25% tariff/subsidy executive order, those movies suddenly cost only $750K, lucky me, I keep $250K. But the trick can’t be repeated. The next order, you will still pay $1M for the cars (supposing there is a domestically produced alternative) but I will only get $750K.

Capt. J Parker

Feb 22 2017 at 10:47am

I think this post is correct and accurate but very misleading.

A 25% tax on imports with a 25% subsidy on exports will have no effect on trade when trade is balanced. When there is a trade deficit, a 25% tax on imports coupled with a 25% subsidy on exports will decrease imports and increase exports, at least in the short run. The problem with such is scheme is not that it will not move the balance of trade in the direction the authors of the policy wish. The problem is the assumption by proponents of such a policy that decreasing the trade deficit via tax policy will be economically beneficial.

John Thacker

Mar 13 2017 at 10:21am

The net effect of the DBCFT is to tax all consumption spending in the USA, which includes tourist services spending. In this it is the same as any VAT. Many VATs do allow a refund for goods, especially for expensive durable goods taken out of the country, but typically not services. That is an interesting question of whether tourist consumption of services in country should be not taxed as well, although it could depend on the efficiency of rebating it. In my experience VAT refunds are only practical for large purchases due to the hassle.

A domestic cash flow tax by itself does not tax domestic consumption. It taxes exports, which are not consumed domestically, and it does not tax imports. By applying the same rate to imports as domestic cash flow and by refunding the cash flow tax on exports, the next effect is a tax only on consumption that does not tax investment regardless of the rate. Without the border adjustment, domestic investment is taxed instead. This is indeed why all VATs are border adjusted.

It is of course fine to oppose the border adjustment, but it is exceedingly strange to do so while claiming to strongly support tax on consumption and oppose tax on investment. There are some good reasons to be skeptical of a sudden and immediate transition – though your normal EMH views would argue that the currency effects should phase in as the plan becomes more likely to pass.

Comments are closed.