It seems like hardly a week goes by without me running into another article suggesting that Japan needs to do fiscal stimulus. Today there’s one discussing the recommendations of Nobel Laureate Christopher Sims, using the “Fiscal Theory of the Price Level” (FTPL):

To revive Abenomics, he [Sims] calls for a co-ordination between monetary and fiscal policy to tackle Japan’s deflation problems and urges the Japanese government to declare that it will not raise the consumption tax in the future.

Now some may wonder why we need a new theory like the FTPL. Wouldn’t it be the same conclusion as an old Keynesian economics? There is a concept called “liquidity trap” where monetary becomes ineffective and fiscal policy would be effective when the interest rate reaches zero.

Well, yes and no. The conclusion may look similar, but the FTPL adds at least three new aspects to the old consensus.

First, the FTPL incorporates the role of expectations. What matters is not the current budget surplus or deficit, but the future path of budget surplus or deficit. In this regard, the government has to commit itself to run fiscal deficit to generate inflation.

Second, the FTPL negates the usual distinction between fiscal and monetary theory. This is a theory for a consolidated governance combining both the government and the central bank of a country.

I am perplexed by this, for a number of reasons:

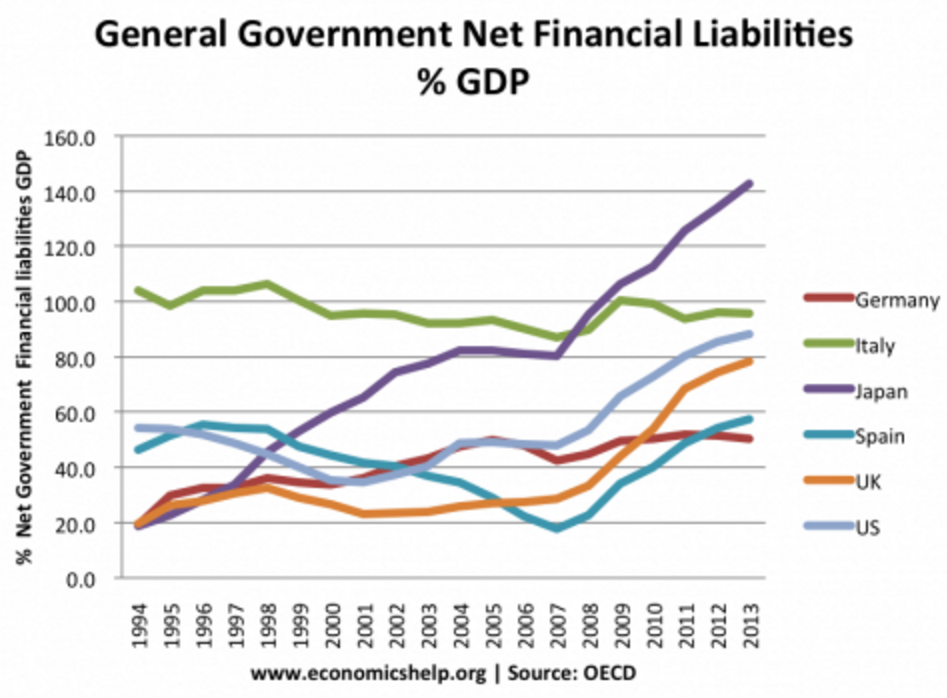

1. Japan did exactly what Sims recommended from 1994 to 2012, and failed as miserably as a policy can possible fail. It combined the largest fiscal stimulus (in peacetime) that the world has ever seen—by far, with the worst performance for aggregate demand that the world has ever seen in a major country—by far. Indeed nominal GDP actually fell. That’s right, even in nominal terms aggregate income was lower in 2012 than in 1994. (The population increased over that period). Here is Japan’s net debt, blowing past Italy to be the highest for any major economy:

The debt ratio soared from 20% of GDP in 1994 to 140% of GDP in 2013. Some people would complain that you can’t just look at the actual debt or deficit; you need to look at the cyclically-adjusted figures. But in Japan’s case that won’t make much difference, except for the period around 2009, as its unemployment rate is only 3%. Japan has a secular growth problem, not a cyclical problem.

But it gets even worse, Japan has recently been doing better than before 2012, even though its fiscal policy has become more contractionary:

As I have argued, Abenomics has delivered some good results, especially in employment, and inflation rate has been higher than that before the launch of Abenomics. Prime Minister Abe likes to say that deflation is over for Japan, but it is still early to declare that.

Unfortunately I don’t have net debt data post-2013, but the gross debt ratio data shows that Japan’s fiscal policy has indeed become less expansionary under Abe. Debt is still rising, but at a slower rate:

This reflects the sales tax increase that Abe implemented. Notice that Japan’s gross debt has now reached an astounding 250% of GDP, far higher than even Greece (number two on the chart.) These are levels that economists used to view as being quite dangerous. Admittedly, the debt ratio is not currently a problem for Japan, as interest rates are quite low. But what if they rise in the future? Greece’s debt situation looked manageable, until it wasn’t.

Of course the other difference is that Japan has its own currency, and could inflate its debt away in an emergency. But should we be reassured by that?

In the end, my biggest problem with recommendations of fiscal stimulus for Japan is not that it will lead to bankruptcy, but rather that it simply makes no sense. Again:

1. They tried massive fiscal stimulus and it failed miserably.

2. When they cut back on stimulus after 2012 the economy did better. Most economists expect Japan to have about 1% inflation going forward. Prior to Abe they had mild deflation. NGDP has risen 9% since Abe took office. That’s not a lot for 3.75 years, but recall that Japan’s NGDP fell over the previous 19 years. And also recall that this 9% rise occurred during a period of falling population, whereas the previous decline occurred during a period of rising population.

3. Unemployment is 3% and falling, and Japanese companies complain they can’t find workers. Immigrants are being brought in to do menial jobs. Unlike the US, the Japanese economy has a high and rising labor force participation rate.

What am I missing here? I understand that Japanese interest rates are zero, but that’s been true for many years. Why do western economists expect a policy that failed for several decades, to suddenly start working? What happened to the view that governments should be responsible, and not push the debt/GDP ratio endlessly higher? And what happened to the view that fiscal stimulus was only appropriate, if at all, during a temporary recession?

The calls for fiscal stimulus in Japan make no sense on so many levels that I’m almost speechless. The assertion seems not just wrong, but preposterous. It would be like claiming that the press doesn’t pay enough attention to terrorism, or the Kardashians.

READER COMMENTS

Thomas Sewell

Feb 8 2017 at 11:16pm

It’s almost like there are some people who want a particular “solution” implemented and the various reasons/problems/theories given for justifying that solution are just window dressing to be changed as needed…

Thaomas

Feb 9 2017 at 8:35am

Could it have to do with observing that other Central banks and even BOJ are reluctant to do what it takes to keep NGDP on a constant growth path? When first-best policies do not seem politically feasible, people turn to second (and worse)-best policies. IETC/minimum wage and “green energy/carbon tax come to mind as other examples.

Scott Sumner

Feb 9 2017 at 10:37am

Thomas, Maybe.

Thaomas, No, because the Japanese tried it for 20 years and it failed as miserably as a policy could possibly fail. Second best policies are policies that actually work. Why don’t economists see that?

Andrew_FL

Feb 9 2017 at 11:02am

You seem to have persistent difficulty understanding that with regard to stated goals, these “second best” policies are actually not-at-all-best policies. For example, with regard to the goal of “keep[ing] NGDP on a constant growth path” you seem to have missed that the point of this post is that fiscal policy has essentially *zero* influence on the growth path of NGDP. That much should be clear from the fact stated above that:

Maybe it would help you to understand that a central back which are, in your words “reluctant to do what it takes to keep NGDP on a constant growth path” are not in fact by not committing to a particular growth path, simply letting some path happen which fiscal policy might influence. Rather the Central Bank, if one exists, influences the path of spending whether it commits to a particular path or not.

Todd Kreider

Feb 9 2017 at 11:26am

Scott,

While I wouldn’t say it as strongly as you did, I have also wondered why some Western economists insist on fiscal stimulus at almost every turn of events for years. I think part of it is that few economists discuss Japan’s economy much and the media keeps going back for their opinions. One is Adam Posner, who has argued since 1999 that Japan’s real problem is that the actual stimulus is far less than what is announced. He even used one year (in the mid 90s) to claim that “fiscal stimulus works when you try.” One data point. Great.

Debt: As with most business journalists, you only state Japan’s debt when it is net debt that should be considered as Columbia economist David Weinstein argued in his 2015 column, “Weak yen is Japan’s best hope for growth.” He wrote that this avoids double counting and added that “the assets and liabilities of Japan’s public corporations should be included in the overall consolidated balance sheet” so that in 2014, the total government debt was 123%. Weinstein additionally wrote that the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet should also be consolidated, giving a net debt of 80%.

Growth: You wrote: “Japan has a secular growth problem, not a cyclical problem.” Japan went through a recession in 1997 probably mostly due to the Asian financial crisis and to a lesser extent a 2 yen increase in the consumption tax. Japan was then affected by America’s 2002 recession and rattled by the US-UK induced housing bubble collapse and financial crisis in 2008. Japan sure wasn’t responsible for the deepest recession since the 1930s.

Interestingly, Japan’s GDP per capita has grown almost at the same rate as the U.S. from 1990 to 2014 except for one five year period, 1995 to 2000 where the U.S. economy was strong while Japan’s experienced almost no growth. And from 2000, Japan and the U.S. have again grown per capita at almost the same rate through 2014.

Harry Chernoff

Feb 9 2017 at 11:27am

Two comments:

1. You may be missing Richard Koo’s balance sheet recession concept. What’s your take on that explanation?

2. If the BoJ does not do any monetary offset for all the fiscal stimulus and, in fact, validates it by buying all the JGBs that pay for the stimulus, how is this any different from your market monetarist approach to NGDPLT (except maybe that even at the gigantic rates of BoJ-financed debt, it’s not enough by your standards?)

Todd Kreider

Feb 9 2017 at 11:48am

correction: Scott, I forgot that you did include net debt and wanted to highlight that Weinstein argues Japan’s net debt is closer to 80% not 140%. We at Team Kreider regret the oversight…

Britonomist

Feb 9 2017 at 12:44pm

Every single time this is brought up I tell you it wasn’t a true helicopter drop as the QE was never promised to be permanent, if it’s not permanent injection it’s not a helicopter drop, period. You’ve previously agreed with this claim, so you must again continue to agree that a helicopter drop has yet to be tried.

Lorenzo from Oz

Feb 9 2017 at 5:39pm

Harry Chernoff: Richard Koo has read Fisher’s theory of deflation, but only remembered half of it. He is all about the debt, not so much about the deflation (i.e. the role of expectations about future income).

Comments are closed.