Years ago I used to enjoy reading Scientific American. Once in and a while, however, they did articles on economics. It was clear that the editors of Scientific American had a very low opinion of orthodox economics, as they would usually publish some sort of silly heterodox article—pop economics—which rejected mainstream economic theory. Perhaps a model using an analogy from a field like meteorology or biology. Thus the business cycle might be equated to some sort of cycle in the natural world, with no discussion of things like demand shocks or sticky prices. Now the American Economic Review (which is the top economic journal) has published a similar sort of heterodox paper by Nobel Laureate Robert Shiller.

Shiller discusses the way that popular fads and “narratives” may influence consumer behavior, and hence the business cycle. My reaction may be more negative than usual, because I know a little bit about the events Shiller is trying to explain, such as the 1920-21 depression and the Great Depression.

The depression of 1920-21 is probably the most well understood business cycle in world history. Until today, I couldn’t even imagine anyone contesting the standard view, which is that it was caused by deflationary monetary policy. If we are wrong about this, we have no reason to have any confidence in anything we teach in the macro half of our EC101 textbooks.

If Shiller is right, then macroeconomics is back to square one. Not back to 1967, before the natural rate hypothesis. Not back to 1935, before the General Theory. More like 1751, before Hume’s writing on money, velocity and business cycles. Is Shiller actually that much of a nihilist? I very much doubt it. More likely, Shiller’s a relatively normal Keynesian, who thinks we do know certain things, such as that a highly contractionary monetary/fiscal policy can cause the unemployment rate to rise. (Please correct me if I am wrong.) Rather the problem seems to be his understanding of macroeconomic history.

Consider Shiller’s description of the 1920-21 depression:

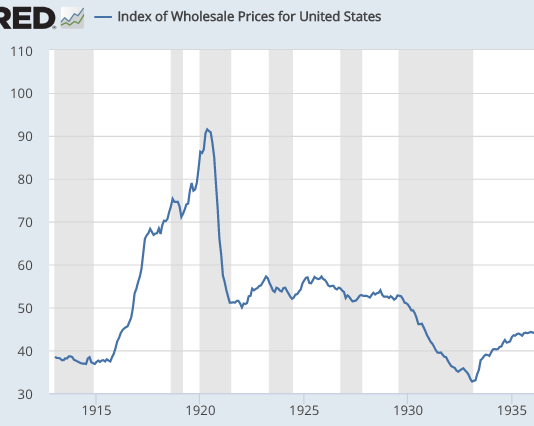

In looking for the narrative basis of economic recessions, which might be hard

to see since narratives are not easy to measure, it would appear that we would have

the most luck looking at really big ones: 1920-1921 was the sharpest US recession

since modern statistics are available. The US Consumer Price Index switched

suddenly from inflation to deflation: between June 1920 and June 1921, during the

Depression, it fell 16 percent, the sharpest one-year deflation ever experienced in the

United States. The Index of Wholesale Prices fell much more: 45 percent over the

same time interval, its sharpest decline ever.

This sort of implies that there is a puzzle to be explained. Why would the price level have suddenly plunged by 16%, the largest decrease ever? Perhaps because the Fed reduced the supply of high-powered money by 15.2% between the fall of 1920 and the fall of 1921, by far the sharpest one-year decline ever experienced in the US? But Shiller doesn’t even mention that fact. Instead he says the following:

Surprisingly, the online NBER Working Paper Series, almost a hundred years

later, when searched, has virtually nothing to say about what caused this spectacular

depression. Why, after all, did it happen?Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz, in their Monetary History of the United States, have given the most influential account. According to them, the 1920-1921 contraction has a single identifiable cause: an error made by the fledgling Federal Reserve to raise the discount rate to trim out-of-bounds inflation in 1919 caused by their carelessly over-expansionary policy right after World War I, leading to a necessity to take strong measures against inflation in 1920. Benjamin Strong, the president of the New York Fed, was on a long cruise starting December 1919, and was unable to prevent Federal Reserve Banks (which did not coordinate their policies with each other so much back then) from raising the discount rate as much as a full percentage point in one shot in January 1920.

This is misleading in all sorts of ways. First, the 1920-21 depression has been studied by a number of researchers. Much less than the Great Depression, but that’s partly because the cause of the 1920-21 recession is so obvious. It’s a simple problem. Second, Friedman and Schwartz’s views are mischaracterized in a way that makes them seem Keynesian. They certainly did not argue that higher interest rates caused the recession, in the ordinary Keynesian sense of causation. Rather they suggested that higher discount rates led to a massive decline in the money supply, and that this is what caused the sharp deflation and depression.

All of these events–World War, the influenza epidemic, the race riots, the Big

Red Scare, the oil shock–were associated with hugely unsettling narratives that

could have led to a sense of economic uncertainty that might have discouraged

discretionary spending of households and slowed down hiring decisions of firms

around the world. These certainly sound like more significant potential causes than

New York Fed President Benjamin Strong’s decision to take a cruise when he was

needed.

This is a weak argument. Start with the fact that it mixes up two issues, F&S’s incidental conjecture that Gov. Strong’s cruise led to the Fed policy error, and the much more important question of whether the Fed’s highly deflationary monetary policy could have caused a depression. Shiller makes it seem like someone rejecting the cruise ship conjecture must also reject the entire orthodox monetary explanation for the 1920-21 depression. That’s just silly.

But it’s even worse. Shiller offers a series of alternative explanations where no alternatives are needed. We know what happened in 1920-21, a deflationary monetary policy. You’d at least think he would have picked an example where the issue to be explained was a mysterious drop in velocity, not a drop in the money supply. I still wouldn’t agree with him, but I could imagine someone arguing that mood shifts among the public might impact velocity. Instead he picks the one depression where velocity seems to add very little to the simple money supply contraction story.

And it’s even worse. After telling us that the CPI fell by 16% and the WPI by 45% in one year, the most in US history, he speculates about possible psychological causes that have no plausible link to deflation. Take his oil shock example. We also had massive oil shocks in 1974 and 1979-80. Does anyone seriously believe those had a deflationary effect? We had very serious race riots in 1965, 1967 and 1968. Hmmm, those were the first years of the Great Inflation. Red scares? Did the 1979 Russian invasion of Afghanistan trigger a deflationary mood among the public? What happened to the WPI in 1979-80? How about the McCarthyism period? The Cuban Missile Crisis?

He also mentions the 1919 influenza epidemic, which may have killed more people than the Black Death. But the Black Death was inflationary, just as the AS/AD model predicts. Indeed all five shocks that he speculates might have cause a big deflation are actually known to have inflationary consequences.

Maybe Shiller’s theory is “it depends”. Sometimes oil shocks are inflationary, and sometimes they are deflationary. But if you are going to make your psychological theory of cycles that elastic, what use is it? I could invent 1000 narrative “theories” to fit any set of time series data.

There’s much more of the same in the paper, indeed almost nonstop speculation about how things like the Japanese invasion of Manchuria or the Russian agricultural policies in the Ukraine might have impacted the mood of housewives in Peoria during the early 1930s.

Yes, I can’t “prove” that any of his speculation is wrong, but nonetheless I find it very dismaying. If this is where we are in macro, if we don’t know anything about what caused the 1920-21 depression, then why have I even bothered to teach monetary economics for 30 years at Bentley? What’s the point of even getting up in the morning and going to work?

One irony here is that I actually agree with Deirdre McCloskey, who argues that narratives are really important in economics. Indeed in my view their importance is underestimated by my fellow macroeconomists. I find much of modern macro to be overly technical, perhaps in an attempt to appear more “scientific”. I believe that narratives are an important part of how we economists learn about the world. When people are accused of “mere storytelling”, I’m usually with the accused.

But saying that narratives help us to understand the world, or even to understand how policymakers see the world, is very different from claiming that narratives actually cause major macroeconomic events. As an analogy, human narratives can help us to understand the physical world, but I don’t think anyone believes that stories cause earthquakes or evolution.

Mood swings might cause business cycles, but Shiller does not present a single shred of evidence in a 35-page AER article. Sad!

PS. I am claiming that the 1920-21 depression is “obviously” caused by deflationary monetary policies. I don’t mean to suggest that changes in high-powered money are the only way of characterizing that policy. Indeed the undervaluation of gold after WWI is an equally useful way of thinking about the “root causes.”

PPS. I’ve always regarded the official data of the 1920-21 downturn to be misleading. The recession technically began in January 1920, but the severe downturn in prices and output only began in September 1920. Until then it was stagflation.

HT: Stephen Kirchner

READER COMMENTS

Thomas

Apr 1 2017 at 12:42pm

What does “once and a while” mean? It’s “once in a while.” As in “seldom.”

bill

Apr 1 2017 at 12:43pm

Shiller gets under my skin. He was giving speeches as early as 1995 that included the phrase “irrational exuberance”. Luckiest man alive that his book came out in March 2000. People want narratives.

Scott Sumner

Apr 1 2017 at 1:29pm

Thomas. Thanks, brain freeze.

Bill, Yes, lucky timing

AntiSchiff

Apr 1 2017 at 1:32pm

Dr. Sumner,

I believe you have a typo in your PS. You referring to a beginning in 1929, instead of presumably 1919.

I enjoyed your post. Unfortunately, Shiller seems capable of making extraordinarily ill-informed comments about business cycles and monetary policy. Yet, his Yale courses online are often excellent.

Craig

Apr 1 2017 at 1:32pm

January 1919 instead of 1929 in the PPS?

rtd

Apr 1 2017 at 2:35pm

Shiller is an author of popular books these days. Akin to Krugman being an author of popular-media articles. Don’t confuse one’s prior (and well-deserved) accomplishments and credentials as relevant to their current objectives. Seems you’re reasoning from historical credentials. Shiller & Krugman are an illustration of moral hazard arising from academic success. Beware & be vigilant.

Andrew_FL

Apr 1 2017 at 3:22pm

Actually all the pre-1929 recession dates are dubious. I think that’s the point at which NBER relies on “detrended” data to pick out the dates.

I’m currently trying to create something like a monthly GDP series as far back in time as I can go based on various series I’m pulling from FRED. Correcting the recession chronology of the 1860-1929 period is one motivation I have for doing so.

Believe it or not most of what’s needed to get a reasonable estimate of GDP components back to 1920 or so does appear to be doable. NX and G are reasonably estimable to the 1860s so far.

Scott Sumner

Apr 1 2017 at 8:14pm

Everyone, Thanks, I corrected it to January 1920, not 1929.

Rtd, When I win my Nobel I promise not to let that happen to me. 🙂

Andrew, Good luck with that. FWIW, I think monthly industry production and wholesale prices are the best way to date early business cycles.

I like the official Fed series more than the revised IP series from Romer and Miron.

Todd Kreider

Apr 1 2017 at 11:40pm

With respect to Krugman, he has a line in the intro of one of his early 90s books that states something close to: “If I ever start writing about things I don’t know much about, please stop me!”

Sociologist

Apr 2 2017 at 12:33am

Seems like he is trying to import the worst kind of “economic sociology” – always criticizing “simplistic models” on purely theoretical grounds without ever providing credible empirical evidence for “thick and rich” cultural explanations. I really hope economics will resist …

Andrew_FL

Apr 2 2017 at 1:07am

Right, INDPRO is gonna correlate well with output & employment when most employment & output is in manufacturing, mining, or utilities.

If you look at FRED series M1204CUSM363SNBR (NBER Macro History Database series m12004c) I think you can see where NBER is getting their start date for the 1920 recession from-like I said, detrended data. This will tend to make recessions seem to start earlier and end later. You can also see this effect in FRED series M12002USM511NNBR (NBER series m12002 “Index of General Business Activity”) or M12003USM516NNBR (m12003, “Index of American Business Activity”) all of which are detrended series.

For the record I’ve been focus on finding analogues to each component of the expenditure formula for GDP rather than using any of these series, mostly because it is the chronology based on these I am trying to check.

Scott Sumner

Apr 2 2017 at 10:00am

Todd, Unfortunately I sometimes do the same in my political posts, but at least I try to avoid claiming expertise in areas of econ where I am not an expert.

Thanks Andrew. I see your point about detrended data. That series declines in 1943 and 1944, but no one would view those as recession years (at least for output and jobs, consumption may have declined.)

James

Apr 2 2017 at 3:19pm

Scott,

You ask “If this is where we are in macro, if we don’t know anything about what caused the 1920-21 depression, then why have I even bothered to teach monetary economics for 30 years at Bentley? What’s the point of even getting up in the morning and going to work?”

Where do you think we are in macro?

Central bankers and policitians want to predict the consequences of their actions. Business people want to anticipate future business conditions. Investors want to anticipate future asset prices.

All of these groups already have access to statistical software, spreadsheets, rulers, graph paper, etc. which means they can extrapolate historical correlations and trends in the variables they care about. That’s what they can do without macro. What would you say is the incremental gain from adding macro theory to their toolbox?

Below Potential

Apr 2 2017 at 3:38pm

Whenever a recession is caused by a demand-shock, there has been monetary policy failure because the job of monetary policy is to stabilise aggregate demand (AD).

Maybe one can differentiate between “normal” monetary policy failure and “aggravated” monetary policy failure.

“Normal” monetary policy failure could be defined as the central bank failing to offset a shock to AD.

“Aggravated” monetary policy failure could be defined as the central bank itself creating the shock to AD (i.e. AD would have stayed stable, if the central bank had not made some change to some monetary policy instrument – a short-term interest rate, the growth rate of base money or whatever else is used as monetary policy instrument).

All that could be argued about is therefore whether some past recession was a case of “aggravated” monetary policy failure or merely of “normal” monetary policy failure, i.e. whether the central bank itself created the AD shock or whether it simply failed to offset some AD shock (which itself might have been caused by some scary “narrative”).

Every hobby historian can go on a hunt for possible narratives that might have caused a shock to AD, which again (by not being offset by monetary policy) caused a recession.

The thing is: it’s not possible to prove or disprove that some narrative played a role in some recession.

In some (or even most) cases it may be plausibly argued that some scary “narrative” had a negative effect on AD. But I see no added value in arguing about that. It’s simply not important. The only important question is this: how can be ensured that monetary policy always does its job of stabilising AD?

I don’t understand why Shiller’s collection of narratives, which could have been done by any hobby historian, made it into the AER.

But I don’t understand either, why,

(as Dr. Sumner wrote in the post).

Let’s assume, just for the sake of argument, that every single past recession constitutes a case of “normal” monetary policy failure and that the respective (original) AD shock was caused by some narrative. So what? None of the insights in macroeconomics (“natural rate hypothesis”, “monetary policy controls AD”, etc. ) would be invalidated.

What Shiller calls “narratives” can be subsumed under what modern macroeconomists refer to as “expectations” (or what Keynes called “animal spirits”).

The only new thing is that somebody now found it necessary to write 35 pages collecting narratives that might or might not have influenced expectations strongly enough to cause a shock to AD and (by not being offset by monetary policy) a recession.

Scott Sumner

Apr 2 2017 at 7:14pm

James, Central banks need to understand monetary policy before they can predict its effects. Predictions cannot be made without understanding how monetary policy causes changes in the economy.

Below Potential, Shiller is offering his narrative hypothesis as an alternative to Friedman and Schwartz. I think he’d claim he’s saying something more that “Yes, tight money caused the recession, but the tight money was caused by narrative X, not the cruise taken by Governor Strong.”

James

Apr 3 2017 at 11:03am

Scott,

Predictions certainly can be made without understanding. I actually listed several ways to do this in my previous comment.

My question to you is this: When central bankers want to predict the consequences of their actions, does the use of macro theory lead to smaller forecast errors than the use of purely statistical models? How much smaller?

Scott Sumner

Apr 3 2017 at 6:59pm

James, I have no idea what you mean by “purely statistical models”. My point is that the better models will be those that are informed by the better theory. After all, you need to know what sort of variables even belong in the models.

Jeff

Apr 5 2017 at 7:21pm

James, the answer to your question is “Sometimes.”

The right way to ask it is to start with a purely statistical model like a Vector Auto Regression (VAR) or the “Bayesian” VAR (BVAR) and figure out what parameter restrictions on the VAR are implied by an economic theory. Then you estimate the statistical model with and without those restrictions imposed, and see if imposing the restrictions improves out-of-sample forecasts.

Imposing restrictions reduces the number of degrees of freedom used by the estimating procedure, and that in turn will reduce the variance of the estimated parameters. If the restrictions are not actually correct, however, this greater precision in estimated parameters will be offset by bias. If the bias is small, because the parameter restrictions are true, or very close to true, the result will be better forecasts. If imposing the restrictions does not improve your forecast, the theory is effectively adding nothing to your knowledge.

My impression is that for macroeconomic data, imposing the restriction that permanent changes in the nominal money supply eventually lead to equivalent changes in prices makes for better forecasts. Most other theories don’t hold up, or only hold up during some periods and not others.

A good example of this is M2 velocity. Two coauthors and I wrote the notorious “P-star” paper in 1989 that basically exploited the stationarity of M2 velocity to improve inflation forecasts. Shortly after we published the paper, M2 velocity stopped behaving like a stationary series and our forecasts became increasingly ridiculous. What I learned from that is what I call the First Law of Econometrics, namely, The Data Are Out To Get You.

Still, I do believe, along with Scott and Milton Friedman that both inflation and deflation are always and everywhere monetary phenomena. And I pretty much agree with Scott about expectations and sticky wages being the mechanisms through which monetary shocks get turned into output fluctuations. But after a career spent mostly at the Federal Reserve (I retired a couple of months ago), I think that’s about all that macroeconomics has been able to tell us about the business cycle.

James

Apr 5 2017 at 10:10pm

Scott,

You wrote: ‘I have no idea what you mean by “purely statistical models”.’

I listed several examples of what I mean. I hate to read you uncharitably but it seems you are trying to avoid my question by changing the subject to whether or not some class of models really counts as purely statistical.

If you believe better theory leads to models which do a better job predicting the consequences of central bank behavior, this is the time for you to start bragging about the track record of your own predictions.

Ross Hartshorn

Apr 7 2017 at 11:21am

You may be interested to know that Dr. Peter Turchin, not an economist but a researcher in historical cycles, has posted a link to this article on his blog, along with some interesting information that he asserts shows the Black Death to have been deflationary.

http://peterturchin.com/cliodynamica/black-death-inflation/

Perhaps you would wish to comment?

Comments are closed.