Stanley’s Milgram‘s “Obedience to Authority” experiments are doubly famous.

First, he supposedly showed that most Americans would shock a total stranger to death because an authority told them to do so.

Second, his experiment was widely perceived as emotionally abusive – so widely, in fact, that Milgram inspired the strict rules that now govern human experimentation. These rules are allegedly so onerous that Milgram’s experiment can never be replicated.

It’s an odd situation: one of the most famous psychological experiments – an experiment that changed the way people think about human nature – effectively prevented itself from ever being doubly-checked.

Recently, though, I was surprised to discover that Milgram’s famous experiment was re-done in 2009! How is this even possible given modern regulations? Experimenter Jerry Berger explains his approach in American Psychologist:

The author conducted a partial replication of Stanley Milgram’s (1963, 1965, 1974) obedience studies that allowed for useful comparisons with the original investigations while protecting the well-being of participants. Seventy adults participated in a replication of Milgram’s Experiment 5 up to the point at which they first heard the learner’s verbal protest (150 volts). Because 79% of Milgram’s participants who went past this point continued to the end of the shock generator’s range, reasonable estimates could be made about what the present participants would have done if allowed to continue.

In other words, since the vast majority of people willing to shock a protesting confederate are also willing to shock an unconscious confederate to death, there’s no need to actually continue to the final, gruesome level. You can run almost all of Milgram’s original experiment without ever bringing the subjects face-to-face with their own extreme moral turpitude.* Berger continues:

I took several additional steps to ensure the welfare of participants. First, I used a two-step screening process for potential participants to exclude any individual who might have a negative reaction to the experience. Second, participants were told at least three times (twice in writing) that they could withdraw from the study at any time and still receive their $50 for participation. Third, like Milgram, I had the experimenter administer a sample shock to the participants (with their consent) so they could see that the generator was real and could obtain some idea of what the shock felt like. However, a very mild 15-volt shock was administered rather than the 45-volt shock Milgram gave his participants. Fourth, I allowed virtually no time to elapse between ending the session and informing participants that the learner had received no shocks. Within a few seconds of the study’s end, the learner entered the room to reassure the participant that he was fine. Fifth, the experimenter who ran the study also was a clinical psychologist who was instructed to end the study immediately if he saw any signs of excessive stress. In short, I wanted to take every reasonable measure to ensure that the participants were treated in a humane and ethical manner.

This meticulous design won Berger a green light from human subjects review. So what did he discover? Milgram replicates nicely:

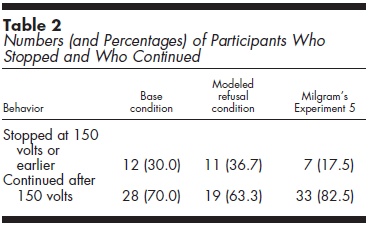

The percentage of participants who continued the procedure after pressing the 150-volt switch was examined. As shown in Table 2, 70% of the base condition participants continued with the next item on the test and had to be stopped by the experimenter. This rate is slightly lower than the percentage who continued beyond this point in Milgram’s comparable condition (82.5%), although the difference fell short of statistical significance…

How Berger and Milgram’s results compare:

Can we properly rely on the truncated version of the experiment? Yes.

I cannot say with absolute certainty that the present participants would have continued to the end of the shock generator’s range at a rate similar to Milgram’s participants. Only a full replication of Milgram’s procedure can provide such an unequivocal conclusion. However, numerous studies have demonstrated the effect of incrementally larger requests. That research supports the assumption that most of the participants who continued past the 150-volt point would likely have continued to the 450-volt switch. Consistency needs and self-perception processes make it unlikely that many participants would have suddenly changed their behavior when progressing through each small step.

Intriguing extension:

seeing another person refuse to continue. In novel situations such as Milgram’s obedience procedure, individuals most likely search for information about how they are supposed to act. In the base condition, the participants could rely only on the experimenter’s behavior to determine whether continuing the procedure was appropriate. However, in the modeled refusal condition, participants saw not only that discontinuing was the option selected by the one person they witnessed but that refusing to go on did not appear to result in negative consequences. Although a sample of one provides limited norm information, it is not uncommon for people to rely on single examples when drawing inferences. Nonetheless, seeing another person model refusal had no apparent effect on obedience levels in the present study.

I’m glad to see prominent psych experiments face the harsh test of replication. But the same biases that lead to the over-publication of shaky results (positive findings are more exciting than negative findings) also lead to one-sided publicity for failed replication attempts (debunking is more exciting than confirmation). When we first hear about Milgram’s original findings, most of us are incredulous. But in the end, it looks like Milgram was correct. With a little high-status prodding, the typical person is ready and willing – though not eager – to do great evil.

* Berger also approvingly cites Milgram’s defense of his original design: “In his defense, Milgram (1974) pointed to follow-up questionnaire data indicating that the vast majority of participants not only were glad they had participated in the study but said they had learned something important from their participation and believed that psychologists should conduct more studies of this type in the future.”

READER COMMENTS

Joe Kane

Sep 25 2017 at 4:46pm

Have you seen Reicher & Haslam’s argument against the usual interpretation of the Milgram experiment?

Mark Bahner

Sep 25 2017 at 5:48pm

Speaking of which, if anyone is missing Ken Burns’ Vietnam (Part 7 is on at 8 PM tonight)…it really shouldn’t be missed. The sentence above applies to all sides in that conflict.

I thank whatever gods may be that I was born late enough not to have to participate in that horror. And my deepest sympathies to those who did, or who lost friends or loved ones.

P.S. Some great music in the series. Part 7 tonight will be start in August 1968, I think. A very appropriate song and lyric would be from While My Guitar Gently Weeps:

Fazal Majid

Sep 25 2017 at 5:58pm

Where were they able to recruit test subjects who had never heard of the Milgram experiment?

Mark Bahner

Sep 25 2017 at 6:27pm

My (wild) guess would be that a majority of adults in the U.S. could not come up with much more than…

I’m pretty sure it wasn’t covered in any class I had in high school or college.

P.S. Search for Barney Fife and the Emancipation Proclamation if you want to see how I think most adults would explain the Milgram experiment.

mbka

Sep 26 2017 at 2:21am

I interpret Milgram quite differently. The primary motive of the participants was quite obviously the desire to contribute meaningfully to an “important experiment”, and they trusted the “authority” on this.

In other words, Milgram’s results are a proxy for social trust and altruism. Altruism not towards the individual that was tortured, but towards the abstract society that was supposedly helped by this experiment.

This is of course the dark side of social trust and of the desire to “do something” for “society”.

Jerry Brown

Sep 26 2017 at 2:54am

Anyone who participates in the experiment has already been talked into participating by people doing the experiment right? How representative are these of the total population? Their participation shows a willingness to conform to the wishes of the experimenters in the first place.

In any event, this is sort of scary stuff that troubles me and causes me to question my assumptions about people in general. Of course, I can just read history and have that happen also.

Fazal, if someone had asked me to describe the ‘Milgram experiment’, I would not know what they were asking, because I would not have recognized the name. But I had heard of the experiment previously, and I think you are right that many others have heard of it also.

Todd Kreider

Sep 26 2017 at 11:05am

Doesn’t anyone listen to Peter Gabriel anymore? Towards the end of his 1985 album, So: “We Do What We’re Told (Milgram’s 37)”

I first learned about the experiment in psych 101 and then heard the song a year later, mostly an instrumental with this at the end.

Milgram’s 37

We do what we’re told

We do what we’re told

We do what we’re told

Told to do

We do what we’re told

We do what we’re told

We do what we’re told

Told to do

One doubt

One voice

One war

One truth

One dream

Mark Bahner

Sep 26 2017 at 6:30pm

“I first learned about the experiment in psych 101…”

What percentage of the population takes Psych 101? My guess would be well under 50% of the adult population takes Psych 101. And then some portion of those would forget the details of the experiment such that I don’t think they’d recognize it if presented to them.

I forget where I read this…but I think someone somewhere wrote that the Milgram experiment demonstrated more dedication to science than obedience to authority. That is, the subjects thought they were helping science, and they saw that as a worthwhile goal. I think that same article made the point that when the scientist, towards the very end, “You have no other choice, you must go on,” all the people balked.

Ah…here’s a web page that describes basically what I recall reading:

Not about obedience after all?

P.S. I would have loved to participate in this experiment before I learned about it. It’s like the John Quinones program, What Would You Do? Very interesting stuff! (And I don’t think finding out I’m a monster would destroy me emotionally. :-))

Todd Kreider

Sep 27 2017 at 12:54pm

It sure burned a hole in my memory in 1987!

I wouldn’t have been able to remember the name Milgram but wouldn’t forget the experiment overall but likely details. I’m sure I saw a reenactment on PBS later so that probably reenforced it.

Comments are closed.